Vanessa H Larson

THE WASHINGTON POST – The human body is something we all know very well – we each have a body through which we encounter the world. Yet each person’s experience is unique.

These differences and shared experiences are explored in a fun, interactive format in You – The Inside Story, an exhibit that opened in November at the Maryland Science Centre in Baltimore. The exhibit engages all five senses through more than 30 activities that kids can try themselves.

“People relate to this exhibit differently than they do to space, to physical science, to paleontology or any other science,” said senior educator at the museum Pete Yancone.

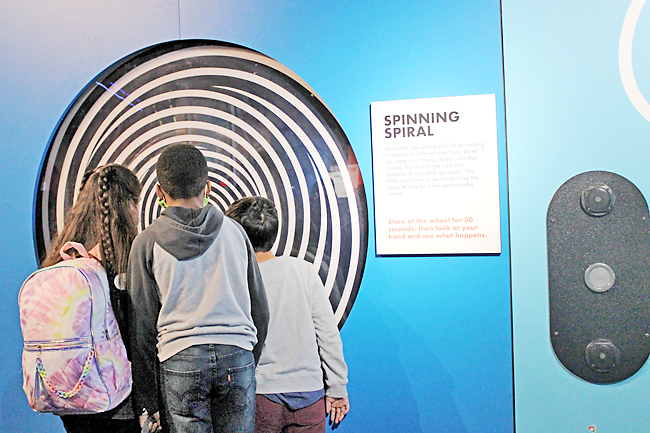

Stare at the spinning spiral for 30 seconds and your brain chemistry will adapt to the movement. Then, whatever surface you look at next – such as your hand or a wall – will also appear to have a pulsating spiral on it, because your brain hasn’t readjusted yet.

The Ames room offers a more fascinating optical illusion: A person in one corner appears to shrink to a fraction of the size of a person in the opposite corner, who looks comically large. This is because the appearance of the chamber has been distorted to trick your brain into thinking it’s a normal square room, when in fact, one corner is much farther away from the viewer than the other.

“It’s such a powerful illusion that even when you know how it works, it still works,” Yancone said. (The room is named after American ophthalmologist Adelbert Ames Jr, who came up with the concept in 1946).

Also popular is the bed of nails, a long-running experience at the centre that has remained on view. You might be surprised to discover that lying on the bed of nails isn’t painful. Because the weight of your body is distributed across 4,788 nails, your skin’s pain sensors aren’t activated, and you’ll probably feel only a mild tickly sensation.

The gross-out section features a kidney stone, a tooth, hair, nail clippings and other human body remnants, all magnified by a microscope. Other stations demonstrate how parasites can be removed from the body, and how a Punnett square (a diagram used in genetics) can predict whether a child will inherit the gene for wet or dry earwax from their parents.

The fart simulator, where kids can manipulate buttons connected to tubes of compressed air to make all sorts of fart noises, might be the highlight for some. The fake flatulence doesn’t come with a smell, but the exhibit doesn’t neglect that sense. A separate station offers blind sniffing, where you can try to identify several common scents without seeing what they are.

Additional activities let visitors compare their balance, grip strength and startle response with those of others. You can test your reaction time pressing lit-up buttons in a game similar to whack-a-mole.

As Yancone puts it: “What we’re providing here are things that should provoke curiosity and wonder about the human body, and especially your human body.”