Research with exotic viruses poses threat of a deadly outbreak, scientists warn

The Washington Post – When the United States (US) government was looking for help to scour Southeast Asia’s rainforests for exotic viruses, scientists from Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University accepted the assignment and the funding that came with it, giving little thought to the risks.

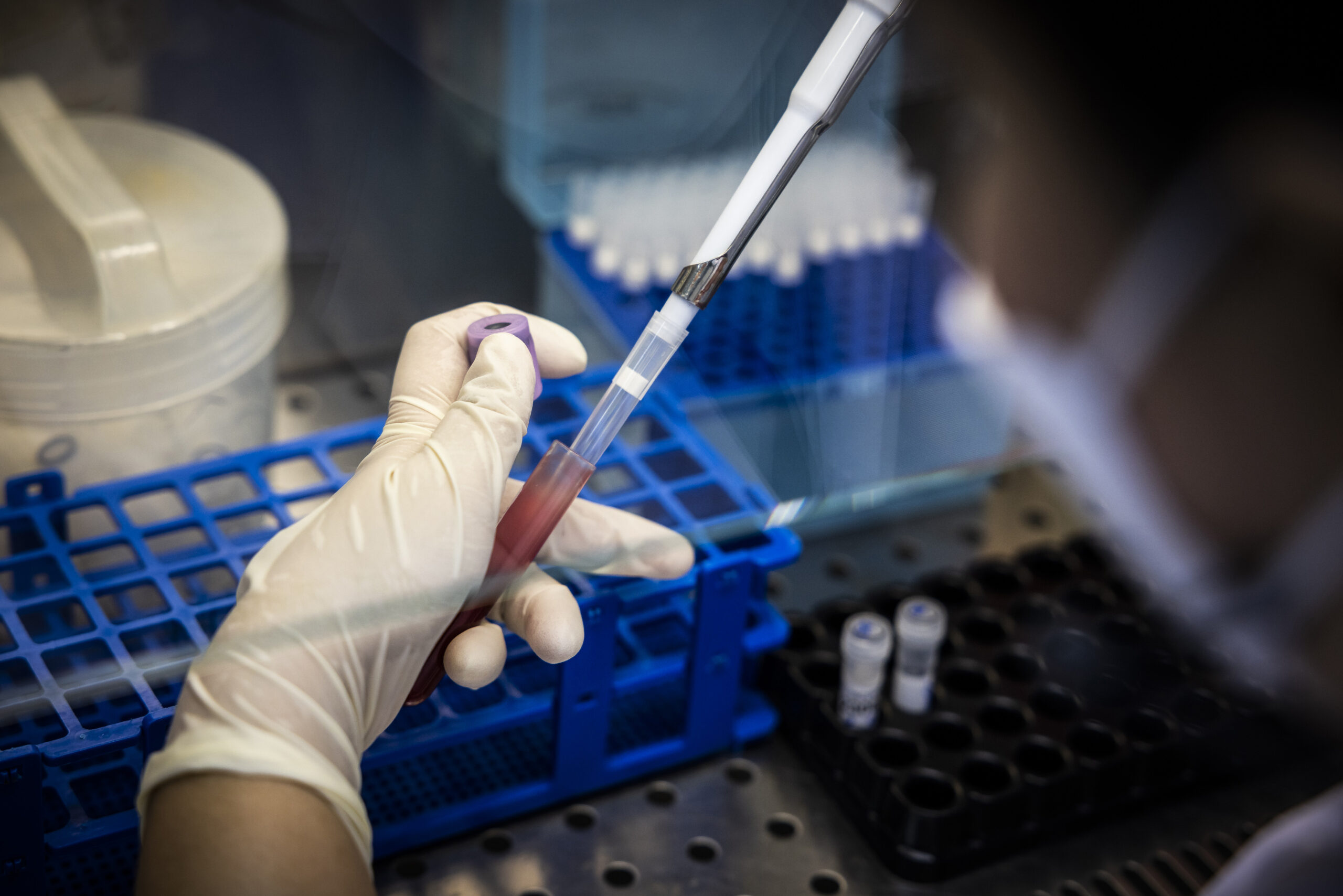

Beginning in 2011, Thai researchers made repeated treks every year to remote caves and forests inhabited by millions of bats, including species known to carry diseases deadly to humans. The scientists collected saliva, blood and excrement from the wriggling, razor-fanged animals, and the specimens were placed in foam coolers and driven to one of the university’s labs in Bangkok, a metropolis of more than eight million people.

The goal was to identify unknown viruses that might someday threaten humans. But doubts about the safety of the research began to simmer after the virus hunters were repeatedly bitten by bats and, in 2016, when another worker stuck herself with a needle while trying to extract blood from an animal.

Some of the workers received booster shots to prevent infection by common rabies, and none of them reported illness, according to their supervisor. But the incidents raised disturbing questions about the research: What if they encountered an unknown virus that killed humans? What if it spread to their colleagues? What if it infected their families and neighbours?

As if to underscore the risks, in 2018 another lab on the same Bangkok campus – a workspace built specifically to handle dangerous pathogens – was shut down for months because of mechanical failures, including a breakdown in a ventilation system that guards against leaks of airborne microbes. Then, in a catastrophe that began in Wuhan, a Chinese city 1,500 miles away, the coronavirus pandemic swept the globe, becoming a terrifying case study in how a single virus of uncertain origin can spread exponentially.

In spring 2021, the Thai team’s leader pulled the plug, deciding that the millions of dollars of US research money for virus hunting did not justify the risk.

“To go on with this mission is very dangerous,” Thiravat Hemachudha, a university neurologist who supervised the expeditions, told The Washington Post. “Everyone should realise that this is hard to control, and the consequences are so big, globally.”

Three years after the start of the coronavirus pandemic, a similar reckoning is underway among a growing number of scientists, biosecurity experts and policymakers. The global struggle with COVID-19, caused by the novel coronavirus, has challenged conventional thinking about biosafety and risks, casting a critical light on widely accepted practices such as prospecting for unknown viruses.

A Post examination found that a two-decade, global expansion of risky research has outpaced measures to ensure the safety of the work and that the exact number of biocontainment labs handling dangerous pathogens worldwide, while unknown, is believed by experts to be in the thousands.

In scores of interviews, scientific experts and officials – including in the Biden administration – acknowledged flaws in monitoring the riskiest kinds of pathogen research. While the pandemic showcased the need for science to respond quickly to global crises, it also exposed major gaps in how high-stakes research is regulated, according to the interviews and a review of thousands of pages of biosafety documents.

The source of the coronavirus pandemic remains uncertain. While many scientists and experts suspect it may have been caused by a natural spillover from animals to humans, the FBI, including Director Christopher A Wray, and a recent Energy Department assessment concluded with varying degrees of confidence that its likely source was an accidental release from a lab in Wuhan.

Within the US, government regulation has also failed to keep step with new technologies that allow scientists to alter viruses and even synthesise new ones. The Biden administration is expected this year to impose tighter restrictions on research with the kinds of pathogens that could trigger an outbreak or a pandemic, according to officials familiar with the matter who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations.

Governments and private researchers continue building high-containment laboratories to work with the most menacing pathogens, despite a lack of safety standards or regulatory authorities in some countries, science and policy experts said. Meanwhile, US agencies continue to funnel millions of dollars annually into overseas research, such as virus hunting, that some scientists say exposes local populations to risks while offering few tangible benefits.

“If you stand back and look at the big picture, the science is rapidly outpacing the policy and the guardrails,” said James Le Duc, an infectious-disease expert who led research for the US Army and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention before founding a maximum-containment lab complex at the University of Texas at Galveston.

“This is a national security concern,” he said. “It’s a global public health concern.”

Hunting for trouble

A few hours’ drive outside Bangkok are lush rainforests and craggy highlands that are home to dense swarms of bats – ranging from palm-sized insect eaters to foot-long species that feast on fruit. Thai researchers had long monitored the bats for deadly strains of viruses known to infect humans, including rabies and severe acute respiratory syndrome, called SARS.

But the virus hunting performed there over the past decade at US government expense included a different goal – to discover pathogens unknown to science.

Chulalongkorn University, Thailand’s oldest and one of Southeast Asia’s top-ranked biomedical institutions, became a hub for US-funded projects that called for the collection and study of viruses on a vastly larger scale. Rather than focusing on pathogens that had made the jump to humans, the goal was to find and genetically evaluate viruses still circulating principally among animals, project documents show. By building extensive databases of these viruses, US sponsors of the research – including the Pentagon’s Defence Threat Reduction Agency and the US Agency for International Development – hoped to forecast which of the microbes might threaten humans.

Thiravat, the physician who oversaw the work with wildlife pathogens, recalled that he initially welcomed the chance in 2011 to partner with American scientists in the Pentagon-funded virus-hunting program called Prophecy.

The following year, the visitors from the US were touting a similar project, called PREDICT, with an overall USD200 million budget administered by USAID. The goal was to identify pathogens “most likely to become pandemic” and prevent such events.

The virus hunting typically started with flights or difficult drives to remote provinces where clusters of trees and networks of caverns provided sanctuary for bat colonies. The Thai researchers would approach the caves and roosting trees at dusk, just as the nocturnal inhabitants were beginning to stir, and work until dawn, catching some in nets and grasping them with gloved hands so that the bodily fluids could be collected on swabs for analysis.

Sometimes, Thiravat removed his cumbersome rubber gloves to make the task easier.

“In the early days, we didn’t think it was that harmful,” he said.

Humans can become infected through direct contact with the bats’ secretions, including their droppings, which are mined as fertiliser in parts of Southeast Asia. “We were really lucky,” Thiravat said, that no one died.

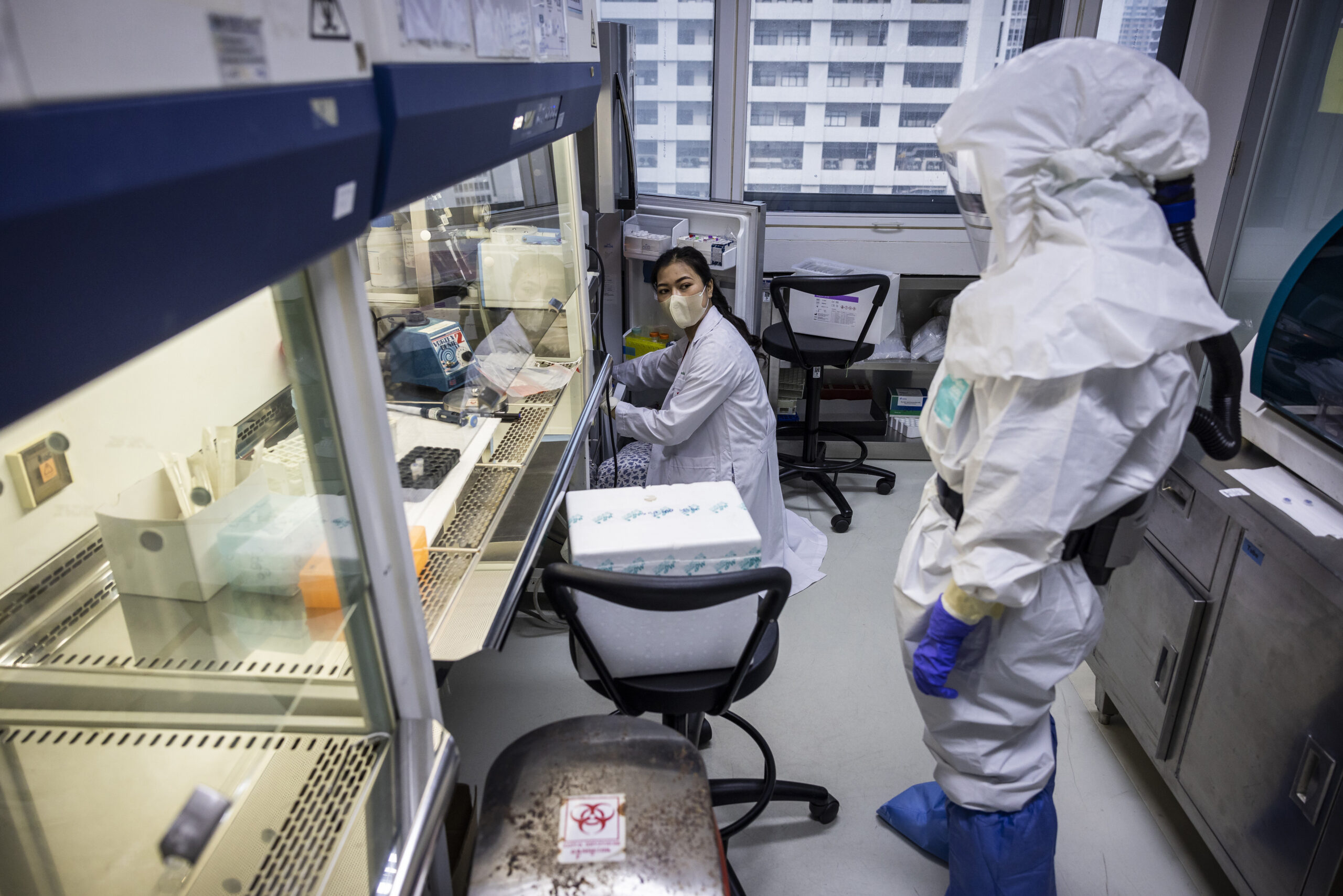

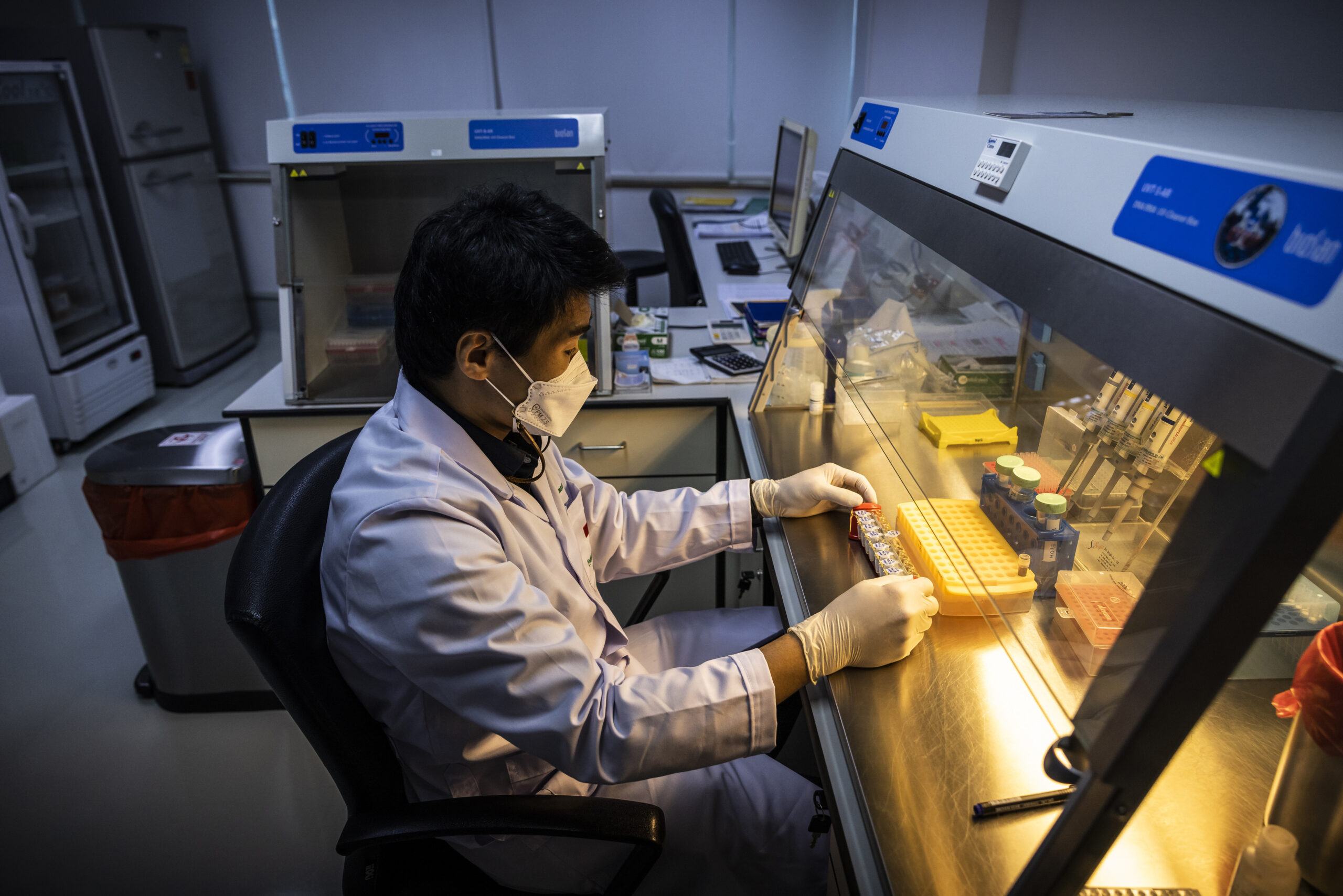

Over time, Thiravat said he grew worried about the risk of accidental infection – in the field, and as the vials of bat material were transported back to his campus lab in Bangkok – where workers clad in protective masks and coats genetically sequenced the viruses using a technique called polymerase chain reaction. Before those analyses began on the lab’s cramped ninth floor, technicians in the field sought to “inactivate” the specimens to prevent the viral material from infecting anyone.

For more than a decade, the process of collection, transportation and analysis played out several times a year. One misstep could invite trouble: a virus-contaminated needle piercing latex and skin in the field, a spill in transit or an equipment malfunction in the lab.

In China, where a separate virus-cataloguing effort has been underway for years, scientists have described being bitten or scratched by bats or having bat urine or blood splashed into their eyes and faces. A 25-year-old American researcher became ill with a Sosuga virus in 2012 after a research expedition to Sudan and Uganda to collect blood and tissue from bats and rodents. She survived after being hospitalised for 14 days upon returning to the US, suffering from fever, malaise, headache and muscle and joint pain, according to scientists. – David Willman