THE WASHINGTON POST – If you could cross Anne Tyler’s novels with strands of DNA from Michael Crichton’s thrillers, you might produce this new book by Ramona Ausubel. From a taxonomic point of view, The Last Animal is a sweet, poignant descendant of Jurassic Park.

Such a strange literary creation sounds unlikely to survive in the wild, but in Ausubel’s laboratory, it springs alive to explore questions that stump scientists and families, problems of the head and of the heart.

The novel opens in Siberia, which is a dark and cold place, but no darker or colder than Jane and her teenage daughters, Eve and Vera, have been feeling lately. A year ago, Jane’s husband, a successful paleoanthropologist, died in a car accident in Italy. Before that tragedy ended his work, the family traipsed around the world searching for Neanderthal bones in French caves and measuring ancient eye sockets in Kenya. Determined to carry on her own research in paleobiology and to keep her daughters close, Jane has brought the girls along on a field expedition to the frozen edge of the planet.

“Couldn’t she have sent us to sleepaway camp?” Eve asked her sister.

Ausubel captures these siblings in all their mercurial passions and desperate loyalties. The girls are witty and precocious, young enough to be crabby but old enough to understand what’s at stake for their mom, the lone woman on a team of chauvinistic scientists. “They had grown up on the road, on the move, in countries all over the world,” Ausubel wrote.

“They had been brave, or else they had no choice. Both felt true, in alternating moments.”

The busyness of their peripatetic lives serves as a distraction from the dull persistence of grief – “heartbreak paved over with a list of to-dos”.

But a more generalised heartbreak haunts these fatherless girls. As attentive listeners frequently carted along to scientific conferences and projects, they’re well versed in the terms of our planetary doom. They know that their mom is involved in a quixotic project to invigorate the Siberian steppe with grasses capable of storing massive amounts of carbon.

Among other things, the plan calls for genetically re-creating prehistoric animals necessary for maintaining the new-old biome.

Ausubel elides the technical details, but she’s not wandering entirely in the land of fantasy.

Two years ago, a multimillion-dollar start-up called Colossal Laboratories and Biosciences announced plans to “de-extinct” mammoths and set them loose to protect the permafrost.

As a practical response to our imminent demise, this plan falls somewhere between Sarah Palin’s “drill, baby, drill” and hoping we can all move to a new planet.

Even Vera, 13, understands what’s at stake. She’s proud of her mom’s work but can’t shake the snake of existential worry curled around her. “It seemed hopeless,” she thought. “It was perfectly possible that the planet would be unlivable in their lifetime.”

That’s a lot for a child to carry: an apocalyptic vision with no chance of salvation. Even the nuclear terror of my teenage years offered the chance of survival under our school desks.

For Vera and her sister – and young people everywhere – the ordinary trials of growing up are roasted by scientific and political fatalism like the world has never known. And it’s that raw despair that Ausubel captures so poignantly, the mix of irony and affection that’s become the final refuge of the final generation.

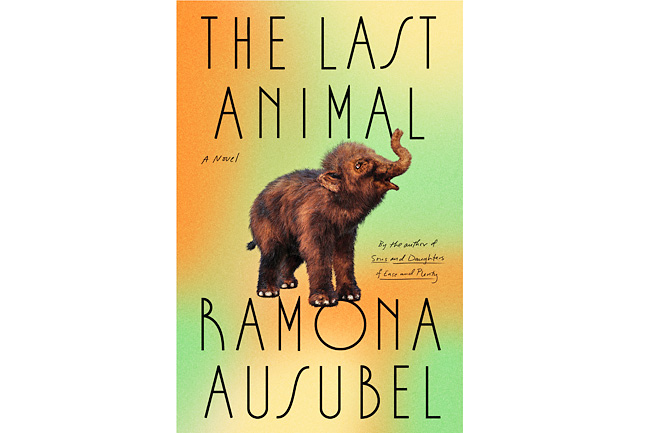

But then a little miracle happens: While wandering around the Siberian mud fields, Eve and Vera stumble across a leathery carcass buried in the soil. After some frantic digging, the girls realize they’ve discovered a perfectly preserved baby woolly mammoth.

And so begins a shaggy elephant story. As Eve said, “Every day is the strangest day yet.”

The quirky comedy of this novel constantly pushes back against the story’s abiding gloom.

The whole book is glazed with a thin layer of absurdity. It’s not just that Eve and Vera are the kind of kids who know a woolly mammoth when they see one. After all, they’ve been raised by a woman who said things like: “Don’t touch the cooler in the bathroom. It’s got iceman samples in it.” The Last Animal has a recessive gene of zaniness that keeps expressing itself when you least expect it – like a dollop of Flubber bouncing through a tale of cutting-edge genetic research.

Jane, sick of being “just” a lab girl, strikes out on her own with a scheme to re-create a prehistoric creature. When Vera timidly objects that “stealing embryos seems maybe bad”, her mother agrees: “It’s unethical and illegal and it has no chance in the world of working.”

But in a rash rebellion against the condescending bros in the lab, Jane takes her grieving family and some exceedingly rare cells to a private zoo in Milan owned by a pair of eccentrics. “I feel like deranged Girl Scouts,” Eve said along the way. “What patch will we earn today?”

“The idea that they were here to make an attempt to reintroduce a species that had been extinct for 10,000 years seemed not only silly but embarrassing,” Ausubel wrote. But here they are with “a few slime squiggles frozen in salt solution” and a fairy tale.

Does their audacious plan succeed? There’s no use being coy when there’s a 200-pound woolly mammoth sitting in the middle of the story. But once this giant baby – christened Pearl – enters the scene, what will happen to her and what she means are up for grabs.

That’s when Ausubel’s story really takes flight, with all the improbable buoyancy of a pterodactyl.

Jane and her daughters quickly realise that while creating a woolly mammoth – “the most important animal on the planet” – is an astonishing scientific breakthrough, keeping the docile beast alive is a complicated challenge.

Pearl is adorable, but as a fuzzy emblem of all the species permanently lost, her cuteness is threaded with doom. And for Jane and her daughters, the animal is a painful reminder of the loved one they can’t bring back. Every family, after all, goes extinct eventually. The paradox that this novel confronts with such tender sympathy and humour is how to love the time we have left.