CALIFORNIA (THE WASHINGTON POST) – It was August 1989, and an 18-year-old Tupac Shakur commanded the stage at the Marin City Festival in California.

“They kept my history a mystery but now I see the American Dream wasn’t meant for me,” he rapped. “Because lady liberty is a hypocrite, she lied to me. Promised me freedom, education, and equality.”

“The fathers of this country never cared for me. They kept my ancestors shackled up in slavery and Uncle Sam never did a damn thing for me, except lie about the facts in my history,” he flowed, confidently striding across the stage. “Now I’m sitting here mad cause I’m unemployed, but the government’s glad cause they enjoy when my people are down so they can screw us around.”

It was one of his earliest concerts, performed soon after moving to the Bay Area – just a couple years before he rose to fame as “2Pac” and became one of the most influential rappers of all time.

Before any of that, Tupac was the son of a Black Panther. He was raised with the ideals of the Black Panther Party, a Black nationalist group founded in Oakland, just 30 minutes east of where he performed during that August day in Marin.

The politically charged lyrics he spit on the Marin City Festival stage carried messages he would go on to share throughout his career, producing tracks that spoke to the injustices faced by Black Americans, Black power and the United States’ failings toward Black communities. His social and political motivations endured – even as he was dismissed as a “gangsta rapper” at the time, including by The Washington Post – during his stardom, encouraging fellow rappers to take on leadership roles to aid their communities.

His upbringing was undeniably shaped by his mother’s – and her comrades’ – Black Panther activism. Their work, in turn, forged his.

“Tupac was born and raised by people who were in the movement, who were movement elders,” said Santi Elijah Holley, author of “An Amerikan Family: The Shakurs and the Nation They Created.” “He grew up among these people who were Black Panthers, former militant, Black liberation activists, and they told him their stories like bedtime stories. Especially his mother, Afeni, always instilled in him this Black pride, self-determination, Black resiliency, resistance.”

“That came through in his music, his lyrics,” Holley said. “He really wanted to use his music, his art, as a vehicle for these messages.”

Tupac’s mother, Afeni, threw herself into the Harlem chapter of the Black Panther Party in 1968 after listening to a speech by Bobby Seale, one of the group’s powerful co-founders. The party was devoted to the protection of Black communities from police brutality, and committed to the causes of universal health care, education and housing. At its height, the party had more than 2,000 members in chapters across the nation, and created free school-breakfast programs, provided sickle-cell anaemia testing and offered adult education.

But it was also a target of the FBI, dubbed by FBI Director J Edgar Hoover as “the greatest threat to internal security of the country.” During federal raids in 1969, Afeni Shakur and 20 other Black Panthers were arrested on charges of conspiracy to blow up police stations and other public institutions in New York.

She became pregnant with Tupac, and spent a portion of her pregnancy in jail, later insisting on representing herself in the high-profile legal proceedings that drew national attention. In May 1971, Afeni Shakur and 12 of her peers were acquitted on all counts. Just a month later, she gave birth to Tupac.

“He would say later in interviews that she raised him to be the ‘Black prince’ of the revolution,” Holley said. “That he was going to carry the torch, take up the mantle….By the time Tupac was born, the Panthers already faced so much repression, and infighting, so his mother and others really expected him to carry on the work.”

In a docuseries, Afeni Shakur said it was her “responsibility” to teach Tupac “how to survive his reality.” In a clip, 17-year-old Tupac said: “My mother taught me to analyse society and not be quiet. If there’s something in my mind, speak it….My mother was a Black Panther. And she was really involved in the movement.”

Tupac’s went on to speak his mind, and speak on society’s ills, on songs such as “Keep Ya Head Up,” “Changes” and “Dear Mama.”

“A song called “Violent,” and a song called “Soulja’s Story,” were really like his anti-police brutality messages,” Holley said. “They’re so raw and visceral, and it’s the same message of Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver and Bobby Seale: we will fight back, we’ve been victimised and brutalised for so long.”

Tupac’s famous “Thug Life” tattoo, stamped boldly across his abdomen, was given its meaning – “The Hate U Give Little Infants F—- Everybody,” a commentary on the impacts of childhood neglect – with the help of another Black Panther, Mutulu Shakur, according to Holley. Mutulu Shakur was married to Afeni Shakur for some time, and remained a lasting father figure to Tupac.

When the young man got the tattoo, to many elders’ dismay, Mutulu Shakur pressed him to develop a grander meaning for it, “beyond just thug life,” Holley said. “Mutulu helped Tupac develop a bigger way of thinking, helped him develop his actual mission.”

Tupac went on to instill his peers with a similar sense of mission that he gleaned from the activists in his life.

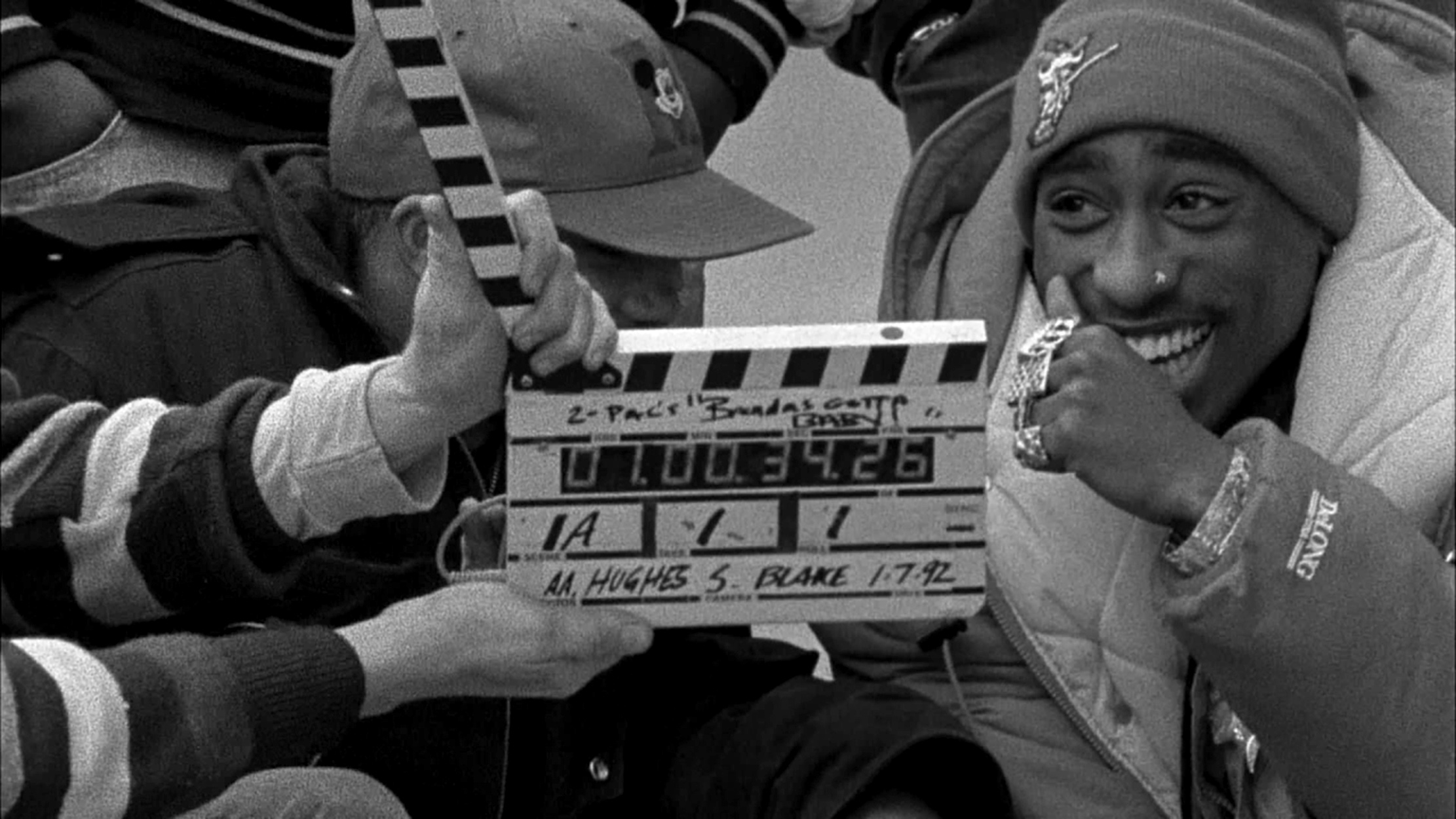

Dupre Kelly, the Lords of the Underground rapper turned Newark councilman, told The Washington Post about his time on tour with Tupac in 1992, and Tupac’s fervour to see Black communities represented by Black leaders – still channelling the ideals he was raised with.

“If you had popularity, he will utilise you, or tell you to utilize yourself, to galvanize the people and bring the people together,” Kelly said. “We had a conversation, and Tupac told me, ‘We have to sell millions of records, so we can turn those millions of record buyers into voters.” Then become legislators, Tupac said, according to Kelly.

“And I said, legislators? Tupac said, yeah, if we don’t become legislators, then the law, it’ll be made for us, by not by us,” Kelly recalled. “We don’t have someone representing us, for us, by us, for the culture.”

Tupac wanted fellow rappers to run for office in their hometowns – Common in Chicago and Treach, the Naughty by Nature frontman, in East Orange, New Jersey. “And he said he would even do it in Oakland or Baltimore,” Kelly said. “I know if Pac were still alive, Pac would at least, at minimum, have been the mayor of Oakland or Baltimore.”

Holley isn’t sure.

Tupac was a “wild card,” not to be confined by the constraints of office, or a suit and tie, Holley said. “He would encourage people that had that ambition. And he’d be doing what he’s always doing: pushing his message through his art.”

That was powerful enough, and Tupac knew that, Kelly said. “Hip-hop did the same things as the Black Panthers – in terms of bringing people together….The Black Panthers told you, we’re going to feed our people, we’re going to galvanise our people, we’re going to educate our people, we’re going to protect our people. And that’s what hip-hop did.”

Tupac’s searing scrutiny of the United States on that Marin City Festival stage was a song called “Panther Power.” The song was never officially released during Tupac’s lifetime – it was posthumously released years later.

The lyrics go on to say: “My mother never let me forget my history, hoping I would set free chains that were put on me.”