JAKARTA (AP) – Centuries-old stone statues and precious jewelleries repatriated by the Dutch government to its former colony are on display at Indonesia’s National Museum, providing a glimpse into the country’s rich heritage that the government had struggled to retrieve.

The collection is part of more than 800 artefacts that were returned under a Repatriation Agreement signed in 2022 between Indonesia and the Netherlands, said the museum’s head of cultural heritage Gunawan. The objects are not just those looted in conflict, but also seized by scientists and missionaries or smuggled by mercenaries during the four centuries of colonial rule.

“I was so amazed that we have all of these artefacts,” said a visitor to the museum in Jakarta Shaloom Azura. She hoped other historical objects can be repatriated too, “so we don’t have to go to the Netherlands just to see our own cultural heritage”.

The agreement to return cultural objects was inspired by the new era of global restitution and repatriation efforts.

In 2021, France said it was returning statues, royal thrones and sacred altars taken from the West African nation of Benin. Belgium returned a gold-capped tooth belonging to the slain Congolese independence hero Patrice Lumumba.

Cambodia in 2023 welcomed the return of priceless stolen artefacts that had been seized during periods of war and instability. Many of the items returned so far have come from the United States (US). And the Berlin museum authority said it would return hundreds of human skulls from the former German colony of East Africa.

The Dutch government announced the same year the return of the Indonesian treasures and looted artefacts from Sri Lanka.

ONLY A FEW OBJECTS MADE IT BACK BEFORE A DEAL WAS STRUCK

The repatriation “is not something out of the blue” but followed a lengthy process, said former Indonesian ambassador to the Netherlands I Gusti Agung Wesaka Puja, who also headed the government’s team tasked to recover the objects.

He said negotiations with the Dutch government have been ongoing since Indonesia’s independence in August 1945, but it was only in July 2022 that Indonesia formally requested the return of its cultural objects with a list of specific items.

“This repatriation is important for us to reconstruct history that may be lost or obscured or manipulated,” Puja said. “And we can fill the gap of the historical vacuum that has existed so far.”

The Dutch government in 1978 returned the famous 13th-Century statue of Princess Pradnya Paramita from the Javanese Singhasari Kingdom. During the same visit to Indonesia, then-Queen Juliana also returned a saddle and spear seized from Prince Diponegoro, a Javanese nobleman considered a national hero for his struggle against colonial rule in the 19th Century.

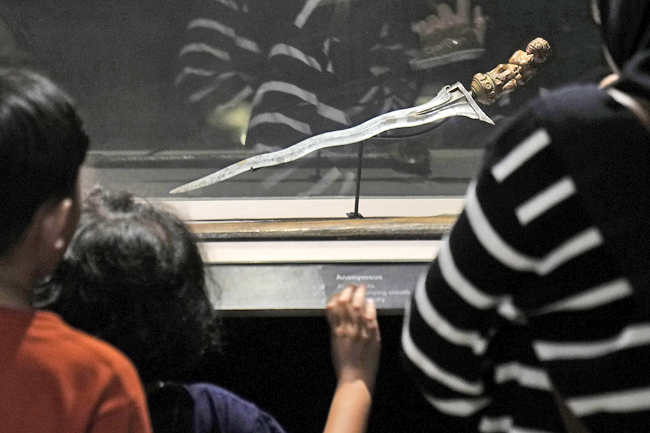

The prince’s scepter was returned in 2015. In 2020, Dutch King Willem-Alexander handed over Diponegoro’s gold-plated kris dagger in his first state visit to Indonesia.

Also pending is the return of the ‘Java Man’ – the first known example of homo erectus that was collected by Dutch paleoanthropologist Eugene Dubois in the 19th Century.

“The importance of the most recent repatriation is knowledge creation, that will give society a more complete knowledge of our past history,” said Puja.

He said the recent repatriation efforts seem to also be motivated by practical considerations, such as when the Delf city administration sent back 1,500 objects in 2019.

They were part of the bankrupted Nusantara Museum collection.

FOCUS ON PROTECTION OF REPATRIATED ARTEFACTS

However, the Dutch ambassador to Indonesia Marc Gerritsen said the repatriation would only focus on cultural objects that are requested, rather than emptying out European museums.

“There is a huge interest from the Dutch public in Indonesian history and Indonesian culture, so we do know that if Dutch museums put these objects on display, there will be an interest,” Gerritsen said.

“But again, the heart of the matter is that the colonial collections artefacts that were stolen during the colonial period are returned on the basis of this process that was established.”

He said the Netherlands, the largest investor from the European Union (EU) in Indonesia, has a unique relationship with Southeast Asia’s biggest economy.

“Of course, we have elements of which we are not proud, but we are really grateful for the fact that Indonesia is so much attached to preserving that history,” Gerritsen said.

To support its former colony in safeguarding its repatriated cultural heritage, the Dutch government has offered to assist in improving museum storage conditions and staff expertise.

Some researchers have criticised Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelago nation of 17,000 islands, for a lack of legal framework to protect its rich cultural heritage and

natural conservation.

At least 11 cases of museum thefts were reported between 2010 and 2020, according to a 2023 report by a lecturer of cultural science at Gajah Mada University Rucitarahma Ristiawan and two other researchers. In 2023, dozens of ships dredged the bottom of the Batanghari River in Jambi province, and the crews looted archaeological objects including porcelain, coins, metal and gold artifacts, which are believed to have been sold abroad, the report said.

“I think there is a lot to be reviewed from our historical works that are still kept in other countries,” said Frengky Simanjuntak, who marveled at the Repatriation Exhibition at the National Museum, on display since October. “So it’s not just about bringing them back home, but how to protect them.” – Ninek Karmini