Christopher Byrd

THE WASHINGTON POST – The camera in Somerville is graceful. It sweeps over objects and characters, tracks them at different ranges from the side, zooms into tight spaces and, occasionally, spins around for a head-on look at events.

The camera’s cinematographic presence is of a piece with Somerville’s excellent audiovisual design. That together with its atypical game mechanics elevate a parochial tale of alien invasion into something more – a reminder that artists can make wonders out of otherwise cliche materials.

At the outset, we’re treated to lulling scenes of domesticity.

A cutscene depicts a young family – father, mother, child and pet – driving home and settling down for an evening in front of the television.

As they doze on the couch, a news bulletin runs before the broadcast abruptly cuts to white noise, waking the toddler.

Watching the boy (now controlled by the player) scamper about, it’s immediately clear that Somerville is a finely animated game; the movements of the characters have an elegant economy to them, like those of a mime.

As expected given the pedigree of Somerville’s developer, Jumpship. It was co-founded by Dino Patti, a founding member of PlayDead who led production on the indie studio’s visually stunning seminal titles, Limbo and Inside.

After leading the kid on a failed expedition to see what’s going on, the player is given control of the father, who must attend to the hungry dog. A house-rattling explosion in the near distance throws everyone into high alert, and upon running outside, you see a monolithic spaceship hanging in the air drawing fire from a cluster of much smaller spaceships.

A short time later, after someone in an armoured spacesuit crashes into the family’s home, the father approaches the person dangling from the partially collapsed ceiling and grasps the hand held out to him. The contact unleashes a small explosion, leaving him in a state that his wife takes for dead.

When we next see him, much in his immediate vicinity has changed. A solid, greyish-red substance covers the nearby area, cutting off access to the floor above.

Following an on-screen button prompt causes coils of blue energy to flicker over the man’s forearm, jolting him awake. Guiding him to a nearby desk light, you discover that when he touches a light source with his newfound ability, the visible light spectrum changes to a bluish hue capable of dissolving the otherworldly excrescence into a rippling liquid, rendered in pretty voxels.

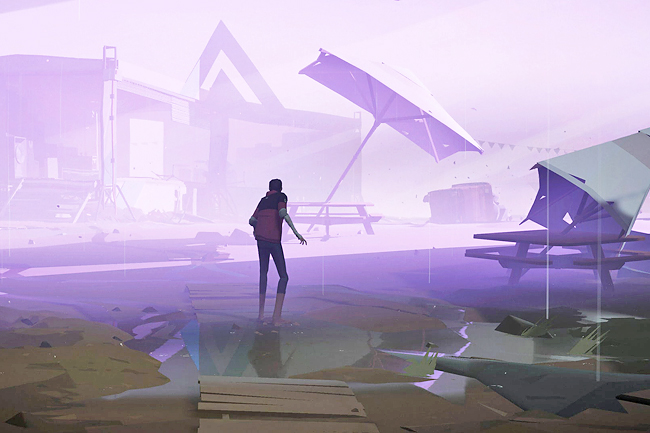

With his dog in tow, the father goes on a journey that takes him across farmland, through a forest, past the desolate remains of an outdoor music festival and elsewhere.

Along the way, he must outfox predatory robots (whose look reminded me of the EMMI in Metroid Dread) and patrolling spaceships that vacuum up every living thing in sight. There is a moment somewhat early in Somerville when you run past the edge of a forest into a clearing and duck into an abandoned tent to avoid being snatched by one of these flying sentinels.

While huddled in the tent, the landscape trembles beneath the bright purplish-white light cast by the alien ship.

There is a stark grandiosity to the scene – as well as to other alien encounters in the game – that works because of Somerville’s remarkable art direction.

Even on a second play through, I was riveted by these and the other ship encounters because of the music and the radiant lights that came with them. The chase sequences are offset by environmental obstacles that make use of the ability to manipulate alien substances.

One scenario finds the father using a cheesy, UFO concert prop to clear the hard alien substance from his path – a visual irony that delights me just thinking about it.

Most of the obstacles in the game require the player to carefully read the environment to see how to proceed.

Usually, that means looking for places to hide, power sources to tap into and alien substances to manipulate.

(You pick up a couple of substance-changing powers before the end). The game does a splendid job of varying the types of obstacles that players encounter, which gives it a very taut pacing.

Somerville reminded me of the qualities that I cherish in adventure games, particularly their ability to plunge one into the unexpected.

I appreciated how its mechanics sidestep the usual weaponry that goes along with science-fiction games. (A gun-toting, super-soldier shows up at one point, but things don’t end well for them.)

Somerville effortlessly pulled me in from moment to moment because I was eager to discover the next audiovisual flourish around the corner.

There is a sequence toward the end where the man revisits places that is particularly captivating for the way in which it makes the familiar strange.

That said, I was a little disappointed with the final scene in the game, which struck me as an overly familiar allusion to the ending of Tarkovsky’s film Solaris.

But that aside, Somerville is the best adventure game I’ve played since Little Nightmares 2.