5 cooking and baking steps where patience pays off

WASHINGTON (THE WASHINGTON POST) – Life is busy when you are getting in and out of the kitchen as quickly as possible while trying to cross items off parenting, work and home to-do lists. I’m in favour of efficiency and shortcuts where they make sense, and life easier.

But sometimes you just have to slow down. I’m as guilty as everyone else when it comes to occasionally getting impatient and speeding through tasks. It’s not always consequential. Other times, it can affect how well your food turns out.

Here are five cooking steps where patience is a virtue. Don’t rush, and you’ll be rewarded.

Preheating the oven

If you’re not waiting for your oven to actually reach the temperature you want it to, you may be in for trouble. Keep in mind that’s not necessarily when the chime goes off. My oven at home and the ovens in our test kitchen routinely beep when the temperature is at least 100 degrees below where I’ve set it, typically 20 minutes prematurely. So if you’re baking or cooking something where browning really matters, wait until the oven comes up to temperature – and confirm it with a stand-alone oven thermometer.

Preheating the skillet

Properly preheating a pan – and waiting until it’s hot to add the fat, in most cases – ensures food immediately browns and crisps rather than sticks or steams. (Enameled cast-iron should never be heated empty, and in the case of nonstick, it’s best to use medium heat for no more than a few minutes.) Similarly, if you are frying food in oil, it’s crucial to hold off adding the food until it’s at the right temperature so that you get crispy, not soggy, results.

Creaming butter and sugar

This is a crucial step in baking that home cooks often rush. To promote rise, many cake and cookie recipes rely on creaming, in which fat and sugar are beaten until light and fluffy. The process incorporates air, with sugar being particularly effective at introducing and trapping air among the fat (which is often butter, but can also be solid coconut oil, plant-based butter or shortening).

Don’t just look for the butter and sugar to combine. The mixture should have lightened in colour and expanded significantly in volume, Mary Jane Robbins writes at King Arthur Baking. You shouldn’t see greasy smears around the edge of the bowl, and if you rub the mixture between your fingers, it should feel mostly smooth and not gritty. Robbins says 2 to 3 minutes at a moderate speed (3 to 4 on a KitchenAid stand mixer) is often sufficient, but what matters most is what’s happening in the bowl and not the clock. Some recipes may take longer depending on the ingredients, or even your ambient kitchen environment.

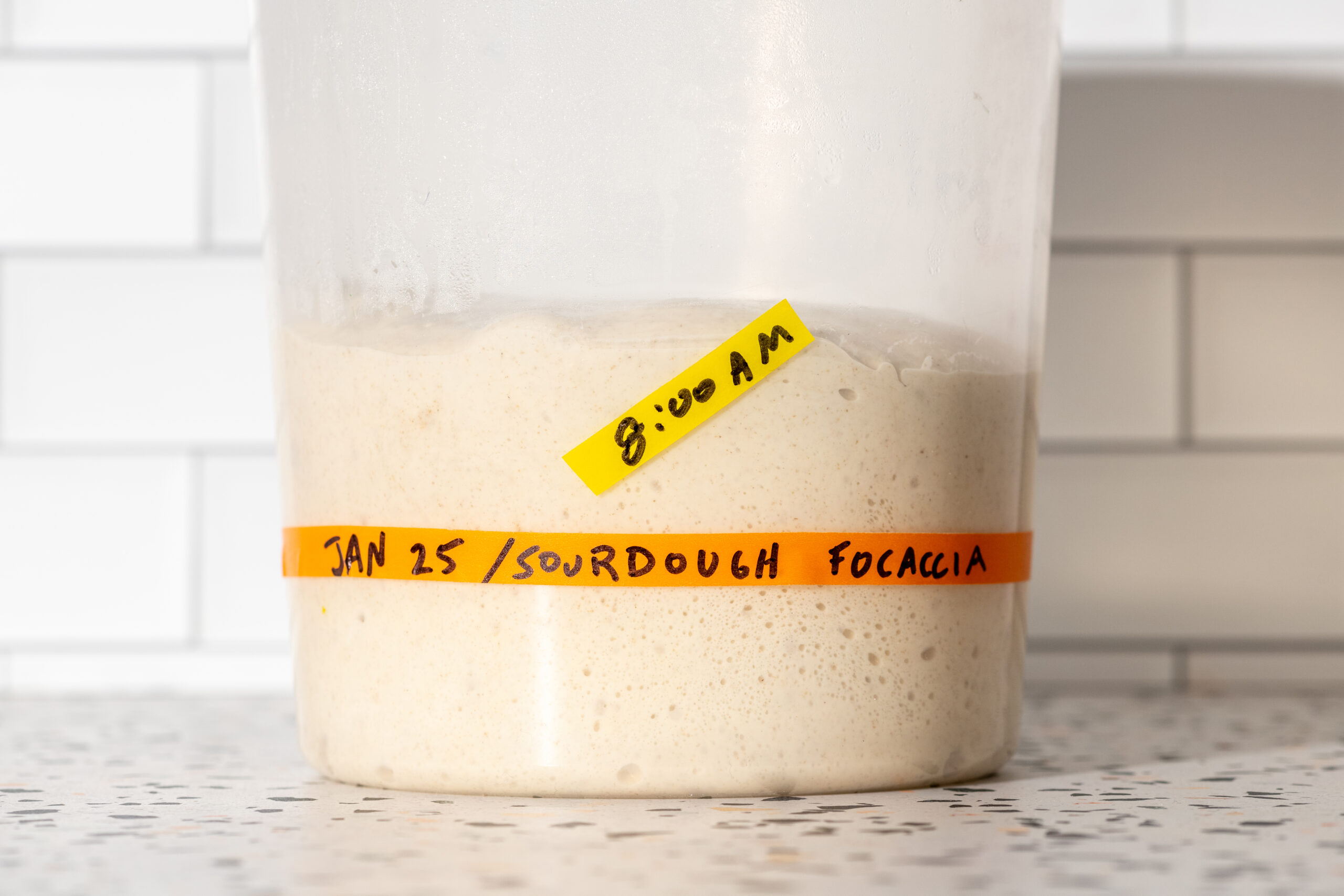

Letting bread dough rise

Whenever I write about bread – most recently about instant vs active dry yeasts – it often inspires readers to email me confessing to their own bread woes. Primary among them: Doughs that don’t rise. As a broad rule, “people almost always underferment,” says Martin Philip of King Arthur Baking, referring to the science of what’s happening as yeasts consume sugar and then flavour and inflate the dough.

If your dough isn’t rising, often the answer is to give it more time. Variations in temperature, moisture and the type of yeast you used can cause dough to take longer to rise than you expect, so be patient. Dough that is properly risen will be domed with a visible network of bubbles. Many, but not all, recipes will specify that it should double in volume. It should feel inflated and elastic when you touch it, like an almost full balloon. Gently poke it with a lightly floured fingertip. If it springs back quickly, give it more time. If it fills back in slowly and leaves a small indent, you’re good to go. (If it doesn’t spring back, you’ve overproofed it, but bake it anyway!)

Waiting to cut bread and cakes

I know, I know. I just told you to wait longer for your bread dough to rise and now I’m telling you to wait even longer after it’s baked? Warm bread can be impossible to resist (might I suggest rolls instead?), but a big loaf really needs time to hang out for the best texture and structure.

“Cutting it hot releases moisture into the air, prematurely halting the process during which starches settle and the loaf temperature equalises. Waiting is similar to allowing a chicken or steak to rest before slicing,” Philip explains in his great book, “Breaking Bread.” Bread that’s cut too early will come across as wet and gummy and may compress as you slice it. Similarly, warm cake may collapse or crumble and feel soggy as well. – BECKY KRYSTAL