Jasmine Hilton

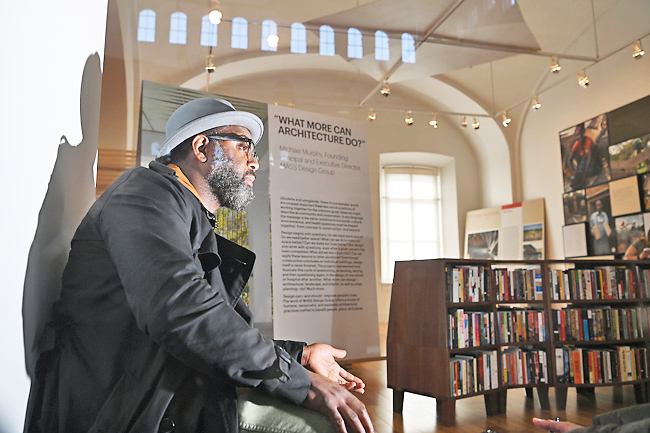

THE WASHINGTON POST – Standing in the National Building Museum, writer Reginald Dwayne Betts placed his hand on the curved walnut shelf filled with books. He picked up a few titles, one after the other, sharing a memory behind each.

Stopping at one with a white cover – Shibumi by Trevanian – he remembered when the spy novel rolled by him on a jailhouse book cart decades ago. Recalling that he didn’t have glasses at the time, he took off the brown and black frames that now sit on his face and got up close to the pages, mimicking what it took for him to the read the book without them.

“All of these books carry a kind of history with them,” Betts, 41, said. “And some of it is just the personal history that they carry for me.”

Shibumi is just one of the 500 books carefully selected to sit on the specially designed wood bookcases – art that is in a museum but is built for a prison.

The signature Freedom Library created by the MacArthur fellow, poet and lawyer is now on display at the National Building Museum in Washington DC, offering people for the first time a chance to see libraries just like it that are being installed in prisons across the country through Betts’s organisation, Freedom Reads. The libraries aim to empower and transform the lives of people in prison through access to literature and beauty – providing books housed in handcrafted shelves designed to encourage community in the centre of prison housing units.

“When you pick up a book, that helps you think about what it means to be alive in the world.

When you have conversations about what it means to be alive in the world, suddenly, you’re beginning to understand yourself better, and in understanding yourself better, you’re better able to communicate something about your future,” said Betts, who was incarcerated at 16.

Each book was selected with care. The Wretched of the Earth. Tender is the Flesh. Black Boy.

There is also Geek Love, The Wedding Party and The Lord of the Rings. From nonfiction to fiction and classic to romance, Betts and his team chose the titles after speaking with novelists, historians, poets and many others.

The space is on display until September in the ‘Justice is Beauty’ exhibit and was created in partnership with Model of Architecture Serving Society (MASS) Design Group, an architecture organisation focused on social justice.

“Freedom Reads libraries transform prison spaces, filling them with inspiration and hope,” National Building Museum President and Executive Director Aileen Fuchs said in a statement.

“This landmark installation within MASS Design Group’s Justice is Beauty exhibition at the National Building Museum adds a new layer of meaning and truly reflects MASS Design’s belief that design can, and should, improve people’s lives.”

The libraries were designed with purpose, Betts said, and to address the challenges of current prison libraries that sometimes can offer only limited time to explore and find books because of the nine-to-five schedule that most people in prison work.

Through conversations with corrections leaders, the library was designed to be no more than 44 inches tall, so as to not obstruct lines of sight in housing units. And the multiple module units can be adapted to suit the space available in a prison. The curved design allows for flexibility to fit different spaces, such as a prison cell converted into a library.

The accessibility of the library, with its open, two-sided bookshelves, is meant to be both inviting and communal, Betts said, making it possible for multiple people to browse together.

Additional reading benches, also designed for the library, can be added to the space.

Each shelf even has a horizontal divider in the middle to keep the books from falling on top of each other. Its careful architecture was one of the most important elements, said Betts, who knows what the inside of prison walls are like and what makes books so important.

“We’re trying to make this broader case about the fact that people in prison deserve beauty,” Betts said. “They deserve access to beauty.”

A devotion to books and reading has been a constant in Betts’ life.

Before being sentenced to nine years in prison in an armed-carjacking case, Betts read The Evelyn Wood Seven-Day Speed Reading and Learning Program book. One of his first jobs out of prison was at Karibu Books, a Black-owned bookstore chain, in Prince George’s County, Maryland. It’s also where he met his wife, Terese.

One of the Karibu owners was so impressed by Betts’s knowledge of books that he asked him where he graduated from college. But Betts said he hadn’t graduated.

“Oh, where are you going?” the owner asked.

“Man, I just got out of prison,” Betts recalled responding.

“Oh, are you a poet?”

To this, Betts said yes. He began writing poetry while in prison and shared some of his poems with the bookstore owner.

Reading was both his “anchor and boat” throughout his time there, Betts said. It also helped him discover what his future could be.

“Being sent to prison at such a young age… made me want to figure out what I wanted to commit my life to. When I said I wanted to be a writer, it had very little to do with my love of writing, because at that point, I didn’t like writing much at all. I had no experience with creative writing,” Betts said. “But in terms of trying to have something that put me in proximity to books, being a writer was that thing.”

The Suitland native graduated from Prince George’s Community College, the University of Maryland and Warren Wilson College before earning a law degree at Yale. He was admitted to the Connecticut bar on November 3, 2017, days before his 37th birthday.

He has published four books, three works of poetry and a memoir.

In the summer of 2020, he created Freedom Reads, originally named Million Book Project, supported by the Andrew W Mellon Foundation. The group aims to put books in 1,000 prisons, one Freedom Library at a time, Betts said.

The first libraries have been installed in prisons in Massachusetts and Louisiana.

Tess Wheelwright, the deputy director of Freedom Reads, said the organisation has been collaborating with state partners to install libraries in housing units in more prisons nationwide, including Connecticut, Illinois, Colorado, North Dakota and California.

The goal is to install 200 libraries by the end of 2023, and 200 every two years to reach 1,000, Wheelwright said.

“People feel cared for, they feel thought of,” Wheelwright said of the feedback they have received from those inside prisons. “We are hoping that people feel supported in their efforts to reimagine what’s possible for their lives.”

In addition to Freedom Libraries, Betts has other projects through Freedom Reads that include creating book circles to cultivate shared reading communities in prisons and bringing writers and authors to prisons as literary ambassadors.

Some years ago, when asked what he could imagine if there were no limits, Betts said his response was that he would put millions of books in prisons. He understands what books can create.

“In some ways, my whole life has been fundamentally intertwined with the possibilities contained in books,” Betts said. “And not just the possibilities within the stories that’s in books, but the possibilities within the stories that you create with others as you read and

contemplate books.”