SURALAYA, INDONESIA (AFP) – Sania sits in front of her home in Indonesia, less than a kilometre from Southeast Asia’s biggest coal complex, where chimneys pump dark grey smoke and a chemical smell into the air.

As countries gather in Dubai for crunch climate talks, the future of polluting fossil fuel coal will be high on the agenda.

For some, the age of coal is now clearly over, and Indonesia has committed to moving away from the fuel despite being the world’s top exporter.

But it is adding two more units to the Suralaya power plant, in Banten province next to the capital Jakarta, and has plans for new plants to power its nickel industry – key to the electric vehicle boom.

Sania, a 37-year-old housewife, is dreading the Suralaya expansion.

“I am very worried. It’s been very scary. I want to move out if I can because our house is too near to the plant,” she told AFP.

“If the units start to operate, the dust here will be much worse. I mop the floor two to three times a day. The noise makes my head ache. The smell is terrible.”

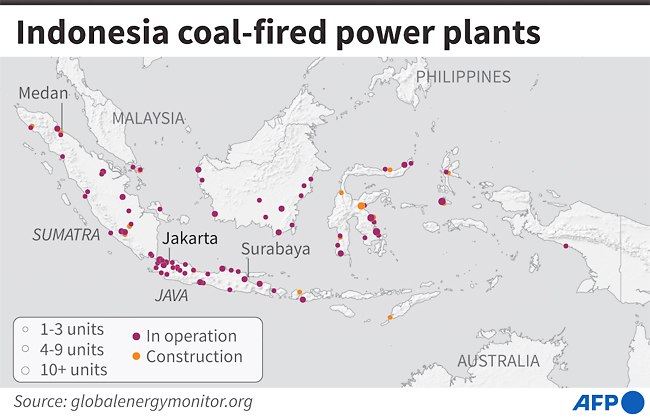

It’s a story repeated across Indonesia, where the government’s pledge to end construction of new coal plants has been tempered by loopholes allowing existing expansions like that at Suralaya to proceed.

The government’s promise also excludes so-called captive coal – plants that power industry rather than feed into the grid.

Indonesia is one of the world’s top coal producers, and is heavily reliant on the fuel for power generation.

But it is also the recipient of a Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP), which promises to mobilise USD20 billion to wean the country off coal.

Under the deal, Indonesia moved up its energy transition goals, pledging net-zero power sector emissions by 2050, and to boost the share of electricity generated from renewable sources to 44 per cent by 2030.

Solar and wind power each currently account for less than one percent of Indonesia’s power mix.

Its JETP calculations do not however account for captive power plants, with more than 13 gigawatts (GW) already installed and another 18 GW planned as of 2022, according to Jakarta-based energy think tank the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR).

Indonesia views these plants as vital to its growing role in the electric vehicle revolution, powering facilities that process nickel for batteries.

It has even mooted designating as “green” coal-powered plants that power EV industry activities.

“There’s a major issue around captive coal power stations in Indonesia, that runs the risk of derailing or slowing that JETP process,” said Leo Roberts, an analyst at climate think tank E3G.

It could mean the deal is not “an effective whole economy transition for Indonesia”, he said.

The Indonesian government, JETP secretariat and state-owned power company PLN did not respond to AFP’s requests for comment.

But Hendra Sinadia, executive director of the Indonesian Coal Mining Association, said efforts to push the country away from the fossil fuel were misguided and some coal-powered energy generation remains necessary.

“Coal is Indonesia’s natural wealth. Indonesia has a significant potential for coal,” he told AFP.

“Coal remains the most relied-upon energy source to drive smelter development, allowing us to become one of the main players in the electric vehicle ecosystem.”

Closing existing power plants is complicated by the relative youth of many of Indonesia’s facilities.

That makes them expensive to retire because of the years of potential returns on investment left.

“I believe choosing to phase out isn’t a wise decision,” said Sinadia.

“Coal remains the cheapest, most reliable, and most accessible energy source.”

But activists say that analysis ignores the planet-warming implications of unrestricted coal use as well as its serious health consequences.

Data modelling by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air suggests emissions from the country’s coal-fired power plants in 2022 were responsible for 10,500 deaths.

“This ‘cheap’ label doesn’t take into account the external costs due to environmental damage and health impacts caused,” said a researcher at Greenpeace Bondan Andriyanu.

Fisherman Hawasi, 55, also blames the Suralaya plant for pollution offshore that has depleted his livelihood.

“There are no more catches in the waters near the shore. We have to sail far,” he told AFP.

“We have been beleaguered by pollution from all directions.”

IESR says Indonesia should retire nine GW of coal generation by 2030 to meet its commitments under JETP. But an energy ministry study released in September proposes retiring just over half that amount by 2030.

This month, PLN’s chief executive Darmawan Prasodjo announced plans to build an additional 31.6 GW of renewable energy capacity by 2033.

But that is expected to largely cater to growing demand, with most existing coal plants left running until the end of their lifetimes.