Illness took away her voice – artificial intelligence created a replica she carries in her phone

PROVIDENCE (AP) – The voice Alexis “Lexi” Bogan had before last summer was exuberant.

She loved to belt out Taylor Swift and Zach Bryan ballads in the car. She laughed all the time – even while corralling misbehaving preschoolers or debating politics with friends over a backyard fire pit. In high school, she was a soprano in the chorus.

Then that voice was gone.

Doctors in August removed a life-threatening tumour lodged near the back of her brain. When the breathing tube came out a month later, Bogan had trouble swallowing and strained to say “hi” to her parents.

Months of rehabilitation aided her recovery, but her speech is still impaired. Friends, strangers and her own family members struggle to understand what she is trying to tell them.

In April, the 21-year-old got her old voice back. Not the real one, but a voice clone generated by artificial intelligence (AI) that she can summon from a phone app.

Trained on a 15-second time capsule of her teenage voice – sourced from a cooking demonstration video she recorded for a high school project – her synthetic but remarkably real-sounding AI voice can now say almost anything she wants.

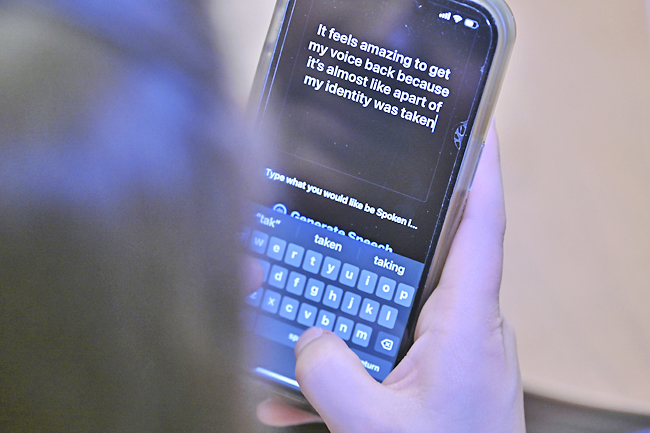

She types a few words or sentences into her phone and the app instantly reads it aloud.

“Hi, can I please get an iced brown sugar oat milk shaken espresso,” said Bogan’s AI voice as she held the phone out her car’s window at a drive-through.

Experts have warned that rapidly improving AI voice-cloning technology can amplify phone scams, disrupt democratic elections and violate the dignity of people – living or dead – who never consented to having their voice recreated to say things they never spoke.

It’s been used to produce deepfake robocalls to New Hampshire voters mimicking United States President Joe Biden. In Maryland, authorities recently charged a high school athletic director with using AI to generate a fake audio clip of the school’s principal making racist remarks.

But Bogan and a team of doctors at Rhode Island’s Lifespan hospital group believe they’ve found a use that justifies the risks. Bogan is one of the first people – the only one with her condition – who have been able to recreate a lost voice with OpenAI’s new Voice Engine.

Some other AI providers, such as the startup ElevenLabs, have tested similar technology for people with speech impediments and loss – including a lawyer who now uses her voice clone in the courtroom.

“We’re hoping Lexi’s a trailblazer as the technology develops,” said neurosurgery resident Dr Rohaid Ali at Brown University’s medical school and Rhode Island Hospital.

Millions of people with debilitating strokes, throat cancer or neurogenerative diseases could benefit, he said.

“We should be conscious of the risks, but we can’t forget about the patient and the social good,” said Dr Fatima Mirza, another resident working on the pilot.

“We’re able to help give Lexi back her true voice and she’s able to speak in terms that are the most true to herself.”

Mirza and Ali, who are married, caught the attention of ChatGPT-maker OpenAI because of their previous research project at Lifespan using the AI chatbot to simplify medical consent forms for patients.

The San Francisco company reached out while on the hunt earlier this year for promising medical applications for its new AI voice generator.

Bogan was still recovering from surgery. The illness started last summer with headaches, blurry vision and a droopy face, alarming doctors at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence. They discovered a vascular tumour the size of a golf ball pressing on her brain stem and entangled in blood vessels and cranial nerves.

The tumour’s location and severity coupled with the complexity of the 10-hour surgery damaged Bogan’s control of her tongue muscles and vocal cords, impeding her ability to eat and talk, Svokos said. “It’s almost like a part of my identity was taken when I lost my voice,” Bogan said.

The feeding tube came out this year. Speech therapy continues, enabling her to speak intelligibly in a quiet room but with no sign she will recover the full lucidity of her natural voice. “At some point, I was starting to forget what I sounded like,” Bogan said. “I’ve been getting so used to how I sound now.”

Whenever the phone rang at the family’s home, she would push it over to her mother to take her calls. Her dad, who has hearing loss, struggled to understand her.

Back at the hospital, doctors were looking for a pilot patient to experiment with OpenAI’s technology.

“The first person that came to Dr Svokos’ mind was Lexi,” Ali said.

Bogan had to go back a few years to find a suitable recording of her voice to “train” the AI system on how she spoke. It was a video in which she explained how to make a pasta salad.

Her doctors intentionally fed the AI system just a 15-second clip. Cooking sounds make other parts of the video imperfect. It was also all that OpenAI needed – an improvement over previous technology requiring much lengthier samples.

They also knew that getting something useful out of 15 seconds could be vital for any future patients who have no trace of their voice on the Internet.

When they tested it for the first time, everyone was stunned by the quality of the voice clone.

Occasional glitches – a mispronounced word, a missing intonation – were mostly imperceptible.

In April, doctors equipped Bogan with a custom-built phone app that only she can use.

She now uses the app about 40 times a day and sends feedback she hopes will help future patients.

One of her first experiments was to speak to the kids at the preschool where she works as a teaching assistant. She typed in “ha ha ha ha” expecting a robotic response. To her surprise, it sounded like her old laugh.

She’s used it at stores to ask where to find items and order fast food. And it’s helped her reconnect with her dad.