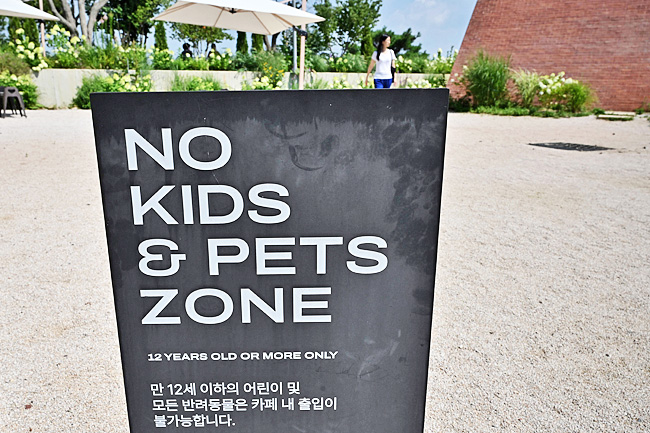

SEOUL (AFP) – The first time South Korean lawmaker Yong Hye-in left the house after giving birth, she ended up in tears when she was denied entry to a cafe because of her baby.

The experience gave Yong, who at 33 is one of the country’s youngest National Assembly members, a new mission: eradicating South Korea’s burgeoning “no-kid zones”.

In a country with the world’s lowest birth rate, the emergence of an increasing number of facilities barring children – such as cafes, libraries and art galleries – is infuriating parents like Yong and, she said, inadvertently thwarting decades of government policy.

Seoul has poured hundreds of billions of dollars into trying to encourage South Koreans to have more babies, offering cash subsidies, babysitting services and support for infertility treatment, but to no avail, with the fertility rate continuing to plummet to new lows.

At 0.78 births per woman, it is far below the replacement rate needed to keep the population size stable, and many experts now said social factors – not purely economic ones – may be driving the decline.

No-kid zones offer a range of official reasons for the exclusion, often pointing to disruptive noise or “inconsiderate” parents, but Yong said it is pure discrimination and impacts young mothers in particular.

“I felt like I had been expelled from society,” Yong told AFP as she recalled her experience being turned away from the cafe after finally mustering the energy to get herself and her newborn out of the house.

She said she had struggled with postpartum depression and “cried every day while breastfeeding”, and was hoping that her visit to the cafe would be a step towards getting back to normal.

Instead, it was the opposite: “I had now become this person who could be so easily rejected – at places like restaurants, cafes and movie theatres. I remember crying so much on my way home.”

South Korea’s National Assembly is itself effectively a no-kids zone, as only lawmakers and authorised staff are allowed inside.

It also has no policy on statutory maternity leave for lawmakers – Yong was only the third sitting assembly member in South Korean history to give birth in office.

When she returned to work she proposed a bill allowing babies under 24 months to accompany their mothers to work.

It is still pending, which she said is no surprise.

“Since the National Assembly is dominated by men in their 50s and older, there is little interest in systems that can combine childcare and parliamentary activities,” Yong told AFP, sitting in her office with her two-year-old son Dan.

“It’s not an urgent matter to them as it does not affect their lives.”

But for Yong, who founded and leads the Basic Income Party, unless the government turns its attention to social issues like inequality and the gender pay gap it will not be able to fix the demographic crisis facing South Korea.

For many young people, “it’s hard to even predict what you’ll be doing to make a living next year”, she said, pointing to sharply rising inequality, which especially affects the young.

Yong worked at a glitzy hotel as a server to support herself during her university years, earning KRW3,500 an hour and working 14-hour days to make ends meet.

Meanwhile, each steak she served cost KRW70,000.

“Even if you worked for 14 hours, your daily salary wouldn’t let you buy that steak you were serving,” she said.

“When you don’t even know what’s going to happen to your own life in a year, it’s a gamble to have a child.”

Yong first came to national attention when she was charged for “unlawfully” organising a silent protest over the 2014 Sewol ferry disaster, in which hundreds of people, mostly schoolchildren, died.

After a six-year legal battle, she was eventually found not guilty in 2020 – the same year she was first elected to the National Assembly on the back of strong support from young voters.

After Sewol, and last year’s deadly Itaewon crowd crush, many young South Koreans have lost faith in their government, she said.

People feel “even if you give birth to your children and raise them, the state would not protect them”, Yong told AFP, adding that for many young Koreans, wanting to be a parent is “considered irrational”.

The no-kid zones illustrate how Korean society views the difficulties of early parenthood – such as sleep deprivation and breastfeeding – as things that women should bear alone, she said.

The male-dominated government may want to boost birth rates, she added, but it would also “prefer it if the noisy, difficult and painful process of raising a child be done separately, somewhere out of sight, on a remote island”.