ANN/THE STAR – There was once a mudfish who pleaded with a squirrel to fetch a crocodile’s liver, as a sick relative’s only cure rested in this organ. The clever squirrel concealed itself within a tempting coconut, which the unsuspecting crocodile devoured, enticed by its appealing appearance.

Inside the crocodile’s belly, the resourceful squirrel burst forth from the coconut and diligently searched for the coveted liver, all while the scaled beast contorted in agonising pain.

After a considerable effort, the triumphant squirrel emerged from the lifeless crocodile, proudly clutching the sought-after liver, which it then presented to the grateful mudfish.

This narrative is just one of the many tales preserved within Malaysia’s indigenous Mah Meri community, now featured in the latest publication by Gerimis Art Publications.

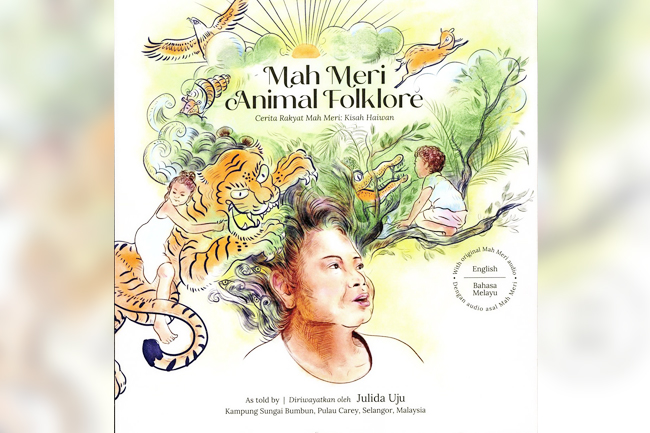

Mah Meri Animal Folklore is a compilation of folk tales revolving around animals, as told by Julida Uju (a Mah Meri cultural activist) and written by Ann Marie Chandy, with illustrations by Sharon Yap (Gerimis creative director).

It is a bilingual book (English and Bahasa Malaysia), with translations by cultural worker Shazni Bhai.

STORYTELLING AND COMMUNITY

Indigenous storytelling is a powerful art form that has been passed down through generations of people and the Mah Meri, like many indigenous cultures, have a rich oral tradition. Their storytellers possess a deep knowledge of cultural history and traditions and are often seen as keepers of wisdom. The beloved stories are not just entertainment but also serve as a means of preserving and transmitting cultural values and beliefs.

But without written records, much of these stories and knowledge have been forgotten over time.

“When our elder told us these stories, he told us to never tell them to people outside our community because they would claim that the stories belong to them,” said Julida, who is also a Mah Meri weaver and dancer from Kampung Sungai Bumbun on Pulau Carey, Selangor.

She is part of the Tompoq Topoh group of weavers, dancers and wood carvers, led by Maznah Unyan.

“But now we have to tell these stories to outsiders, otherwise these stories will be lost because the young Mah Meri are no longer interested in hearing and learning these stories.

It is very important for future generations to know and learn these stories because our old stories cannot be found anywhere else, only in Mah Meri,” said Maznah.

Julida recalled how she and the other children in the village would listen, spellbound, to her grandfather telling stories in the evenings. And what a performance he gave, with gestures and sound effects accompanying his narration.

“I never expected that all the time I spent listening to the stories, that one day they would be made into a book. I hope the young Mah Meri will be interested in our stories; and that parents will teach these stories to their children,” she said.

For Julida and Maznah, they hope that the stories will be passed on to their grandchildren and for the larger community to know about them.

“With this book, our stories will carry on until the end of our lives,” they said.

PRESERVING KNOWLEDGE

Mah Meri Animal Folklore took about half a year to complete, but it was preceded by several years of trust-building and friendship with the community.

“When we started Gerimis, we wanted to bridge the gap between what the public or the world at large understands about our Orang Asli and what the Orang Asli truly are when they tell the stories themselves.

“In a way, to bring together worldviews and find that universal understanding between the two.

“We hope this book will be able to educate the public, and inspire a collective action or care towards upholding Orang Asli rights and protecting our planet,” said Gerimis Art’s co-founder Wendi Sia, who edited the book.

Meh Meri Animal Folklore is a colourful book with lively illustrations complementing the stories.

“When we first listened to the stories, we laughed a lot – the stories are witty, funny and also full of lessons. We thought it was suitable for children to read them and therefore used colourful illustrations like most children’s storybooks,” said Yap.

Each story is accompanied with a Did You Know? section with interesting facts, Points To Ponder or simply, the moral of the story.

“Some recurring themes are being witty, clever, and to outsmart opponents bigger than you are and that size does not matter. This is very reflective of Orang Asli’s position within our political and social landscape – although a minority, they are utterly resilient and have historically endured exploitation and oppression by the powerful.

“It also reflects how they must always be quick on their feet and thinking when in the forest and in their everyday lives, showing that they are also resourceful, while being resilient,” said Sia.

Included in the book are behind-the-scenes photos from the Pulau Ketam excursions, for readers to put a face to the people who tell these stories, see the place where these stories originated from, and bring them closer to the storyteller and the Mah Meri people.

Sia noted that through this book, readers can learn about the ways of the Mah Meri’s world and their views. It is an invitation into their world, which would otherwise be very far away for most people.

“To the Orang Asli, the forest is alive with seen and unseen creatures, and a lot of their customs or adat are practiced in respect to the plants, animals and non-human beings of the place as a way of living as one with the land.

“We want readers to understand the Mah Meri’s closeness to the land, that their stories reflect the ecosystem within which they live in and its richness and diversity, as well as their deep respect for the land.

“By fostering this understanding, we hope that more people would adopt this worldview into our everyday lives where we care for the earth and the lives within it,” said Sia.

In taking things forward with the Gerimis grassroots platform, Sia and her team hope this book can be used as an example to be shown to the other Orang Asli communities on what can be done similarly in their village and among their people, and perhaps also serve as a “memory jogger” to the elders.

“We have met a few Orang Asli who shared their wishes to document or record their histories and folk tales. We must also remember that because of their oral traditions, most of their histories are not recorded in any form except by memory, and because of this, the legitimacy to their customary or ancestral lands are constantly challenged or exploited by people with power. Therefore, the evermore importance of written documentation of their oral histories and stories,” she added. – Rouwen Lin