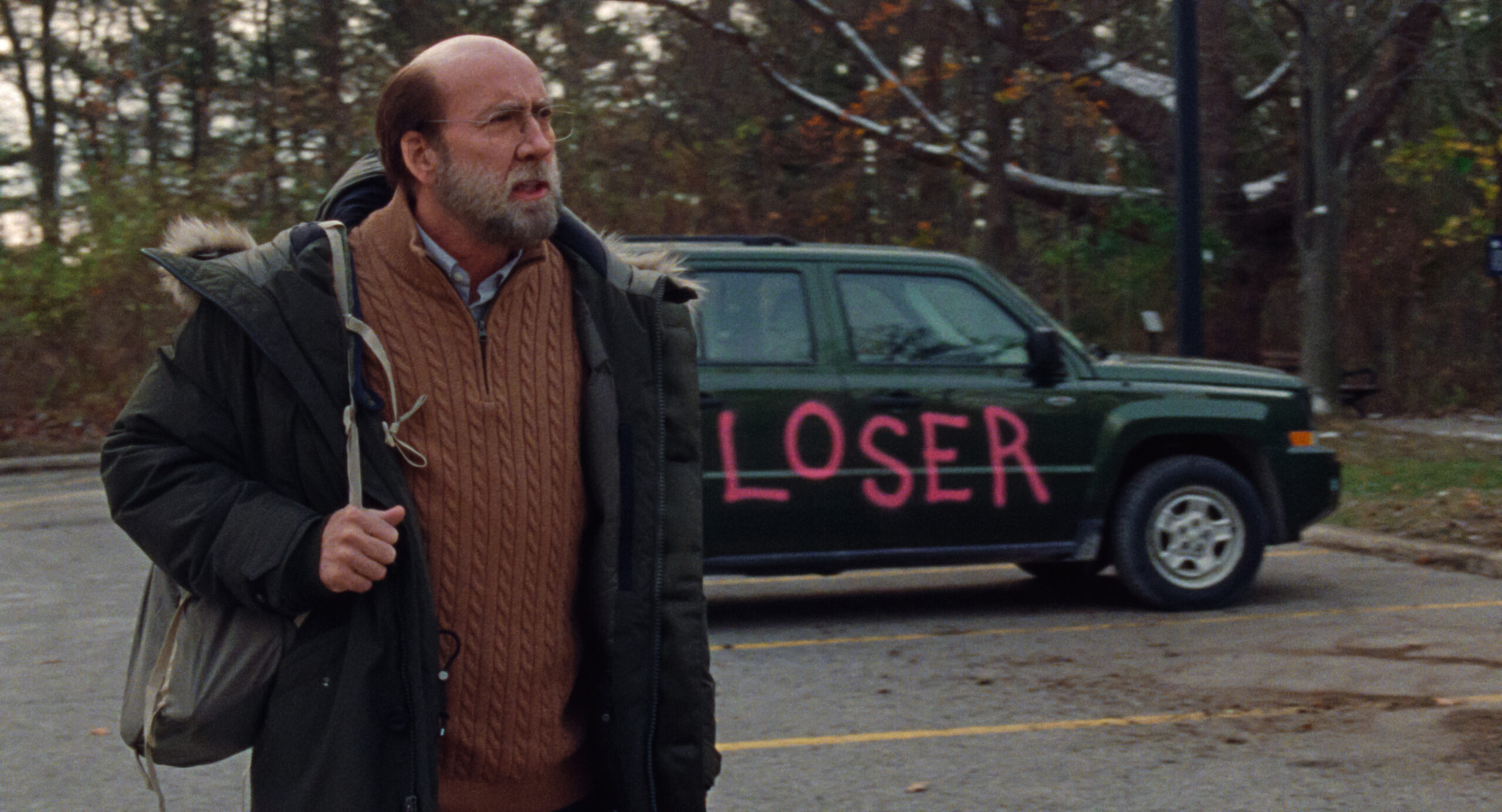

WASHINGTON (THE WASHINGTON POST) – On the surface, it wouldn’t seem as though beloved, mega-famous superstar Nicolas Cage has anything in common with Paul Matthews, his character in A24’s horror-comedy “Dream Scenario.” Paul is a mild-mannered, badly balding evolutionary biology professor who just wants somebody, anybody, to clock his existence. His students gab through his class as if he isn’t there. A colleague steals his idea because Paul is too stuck in his head to commit it to paper. A “friend” throws raucous dinner parties that he’s pointedly not invited to. That is, until Paul starts appearing in the dreams of millions of people and becomes an actual overnight sensation. The most interesting man in the world – a Nicolas Cage! – just without any of the charm to sustain the eyeballs now pointed at him, particularly when all those dreams start to turn into nightmares. (The Washington Post’s Ann Hornaday calls Cage’s performance “delightfully, derangedly meta.”)

Since the beginning of his career, Cage, 59, has earned a reputation for his total, physical commitment to every role, from being dragged across concrete as an ex-con he has called “an outlaw version of Woody Woodpecker” in “Raising Arizona” to channelling John Travolta while simultaneously playing a murderous psychopath in “Face/Off,” one of the most unhinged blockbusters ever made. In “Dream Scenario” (only the second film from Norwegian director-writer-editor Kristoffer Borgli), Cage dives into a parable of internet fame and cancel culture that allows for a ton of outrageous visual setups involving crocodiles, falling objects and plenty of jump scares. The Oscar winner, who has made 112 movies and has four yet to release, spoke to The Post from the set of his new psychological thriller “The Surfer,” about a man who decides to get revenge on a gang of surf-rats who’ve taken over his childhood beach.

Q: It’s already dark here on the East Coast and you seem to be calling from someplace very sunny. Where are you?

A: I’m three hours outside of Perth, Australia, at the tip of the continent. I’m pretty remote at the moment, so I’m glad we have a good connection, and I do like your cactus (poster) behind you. That’s awesome. Prickly pears and everything.

Q: Oh, thanks! It’s an homage to New Mexico, which is where I’m from.

A: Well, I live in Nevada, so I have a saguaro and a Joshua tree, so that’s nice. Right now, I’m in a surfer’s house that I’m renting. And my set is only five minutes away. It’s a beach. And I’ve been watching all the surfers and really enjoying their dance on the waves.

Q: Have you been getting out there, too?

A: I don’t really get to surf in the movie. It’s almost an existential crisis. It’s sort of like Albert Camus’s story of surfers. They only need me on the board sort of watching the beach. But some people in surf magazines have been taking video of me getting clobbered by the waves and saying, “Just hang in there, Nick! It’ll get easier, I promise!” (laughs) There’s also white sharks out there. But one day when I retire, I’d like to go and learn to surf in a place that doesn’t have all the sharks and just sort of have it be the last chapter.

Q: “Dream Scenario” is a very fun, surreal movie. When you read the script, did it just feel like, “This is insane and I have to make it?”

A: I don’t know if it was insane as much as it was one of the five best scripts I’d ever read in over 42 years of doing this. The others were “Leaving Las Vegas,” “Vampire’s Kiss,” “Raising Arizona” and “Adaptation” – and “Dream Scenario.” All of those scripts I said right away, “I have to make this movie. It’s very important to me that I make this movie.” And I think it’s because “Dream Scenario” in particular gave me almost a cathartic opportunity to express some feelings that I had developed over the years, even though Paul was designed to look nothing like me.

I had gone through something in 2008, 2009, where I stupidly Googled myself and I saw this thing called “Nicolas Cage Losing His you-know what.” And it’s just cherry-picking, cobbling together all of these meltdown moments, crisis moments of different characters that I played throughout the years without any regard for Act One or Act Two or how the character got there. And yes, it was funny, but it just started growing exponentially and turning into – I guess I coined a new word. I became memified. And there were T-shirts and little faces, like, “YOU DON’T SAY.” I was like, “Well, that wasn’t really what I had in mind when I decided to be a film actor.”

When I started out in the ’80s, we didn’t have the internet. We didn’t have cellphones with video cameras. And it’s not what was going on with the golden age actors that I was inspired by. So it was an adjustment. I was confused by it. I was frustrated by it. I was even a little stimulated by it. But I didn’t see any of it as an argument for good. And then as it kept happening, I thought, “Well, maybe there’s something good here.” Maybe it will compel some young person on the internet to go, “I want to see that movie now. How did that character get there?” But it wasn’t until I read “Dream Scenario” that I thought, “Yes, I can apply those exact feelings that I had.”

Because it’s not unlike what Paul’s going through with his dreamlike viral experience. At first he’s excited by it and then it turns on him and it becomes not dreams but nightmares. And that’s not unlike the experience of fame. Fame itself is not unlike gambling where you can feel like, “Yeah, I’m winning, I’m on top of it.” But then when fame turns on you, when you start losing at the table, then it becomes even more profound. I think that’s why gamblers get addicted, because they’re actually gambling to lose. They’re feeling more when they’re losing.

Q: There are so many vivid dreams you get to enact in the movie. Were there any that you really enjoyed actually doing?

A: There’s one dream in particular where we didn’t quite know what we were going to do. But Paul’s daughter has a nightmare in her bedroom. And I thought, “Why don’t I come out of the closet and start marching really fast toward her?” To me, that’s funny and scary simultaneously. And then Kristoffer, the director, said, “Well, you should do it but have a big smile on your face.” So that’s a great example of how we were collaborating together. He brought the smile. I brought the march.

Q: You said Paul was designed to look nothing like you. How did you two collaborate on that?

A: Kristoffer sent me pictures of different professors, and we tried to model (Paul) after that. It was important to Kristoffer that we change the shape of my nose because, however much I connected with Paul Matthews emotionally, we wanted to make sure that people would forget about so-called Nick (he prefers the k on the end) Cage and they would only see Paul Matthews. But I thought, “If you’re going to do that, you have to change the voice,” so you weren’t thinking about my cadence and my sort of Mojave drawl, if you will.

Q: Did you model the voice on anyone in particular?

A: No. Sometimes when I make a character I have specifically modelled my voice. Like “Vampire’s Kiss,” it’s well-known I modelled it on my father, and in “Renfield” when I played Dracula. But I’m always trying to find things I can do sonically that I think would add to the character.

I started making movies very young. I was 16 when I shot “The Best of Times,” which was a TV movie and “Valley Girl” shortly after, and I didn’t think I had a good voice. And all my heroes were people that I could imitate: Bogart, Cagney, Eastwood, Brando. They all had interesting voices. And I didn’t have a voice that I thought had any strength. So I actually spent time developing my voice to try to give it some distinction. Just for me as a person who makes movies. But when I’m creating a character, voice is one of the first hooks into how to play a part. And it was for me with Paul.

Go all the way back to “Peggy Sue Got Married,” Charlie Bodell. That was the most outer space I went with a voice because I like to challenge myself. It’s common knowledge I didn’t want to make the movie. So if I’m going to make the movie, it better be something that I can learn from and have some fun with. And I grew up watching that silly “Gumby” show and his Claymation horse Pokey would talk like that (does Pokey/Charlie Bodell’s voice.) I thought, “Okay, can I actually play a character that talks like that [does voice again] in a movie and make it work?” That was the challenge. That was what was fun to me about it.

Q: My favourite scene in “Dream Scenario” is when Paul starts engaging with a young woman, played by Dylan Gelula, who had a sex dream about him and wants to reenact it. It’s so awkward. What were you thinking going into that?

A: When I read the script, I knew right away that it would just be hilarious in the worst way. And Dylan is so good in that scene. Oh, my gosh. But Kristoffer was very clear that we’re not going for comedy for comedy’s sake or laughs for laughs. Yes, it is funny. But it’s actually a situation that’s really painful. So that I was looking more at the genuine, “If that really happened to me, how mortified would I be?” He’s over his head. He’s in a dynamic where he’s lost and it’s an impossible situation.

Q: You must have had to shave your head in this balding pattern and then live with that hair when you left set. Was it interesting to move through the world looking so different from yourself?

A: Any time you get to change your appearance for a character and live with that appearance, it helps keep you working on the performance, on the character. When I did “Birdy,” and that was a long time ago, I never took the bandages off. Not when I would go home. I slept in them. I was getting a bad rash. But the experience I had looking at people looking at me with that bandage on my face and people laughing at me, I was like, “Wow, if this was real.” It really makes your heart go out for people that have been burned or it put profound compassion in me, having just touched the tip of something like that. And so that all went into the performance. So I think in terms of character, living it somewhat is always helpful in terms of informing the performance. Not necessarily going method all the way, but just having a taste of it. A feeling of it.

Q: And Paul’s kind of invisible. People look right through him.

A: Yeah, that’s true.