THE WASHINGTON POST – One summer when I was 13 or 14, I began telling scary stories to the younger kids in my neighbourhood. I’d sit on our front porch steps after supper and in the growing twilight launch into some shivery classic such as The Hook.

That’s the one about the teenage couple and the deranged killer. At other times, I’d perform abbreviated versions of eerie classics from Basil Davenport’s Tales to Be Told in the Dark and Bennett Cerf’s Famous Ghost Stories. The kids loved these spooky evenings.

Their parents – not so much. My mother started receiving phone calls from other mothers, complaining that their children were having nightmares, if they could fall asleep at all. So, my evening re-creations of WW Jacobs’ The Monkey’s Paw and Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart came to an end. But in the years since, I’ve continued to enjoy traditional ghost stories and weird tales, gradually filling a substantial bookcase with “many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore”, as well as numerous modern works of occult and supernatural fiction.

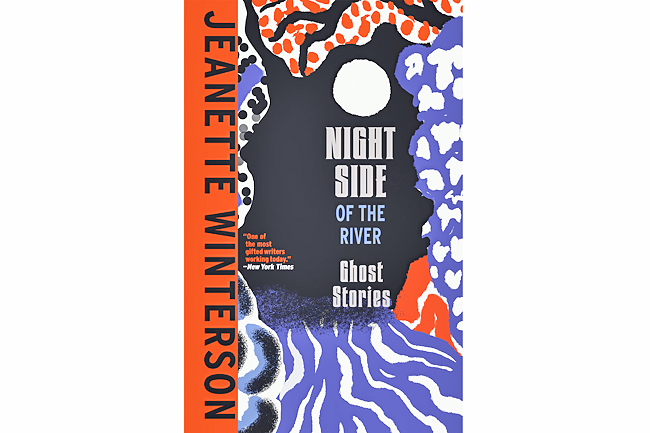

This past week, for instance, I read Jeanette Winterson’s Night Side of the River: Ghost Stories and then turned to Phyllis Paul’s beautifully executed, deeply unsettling 1960 novel, Twice Lost. Paul’s book, recently reprinted by McNally Editions, is enigmatic and ambiguous in the way of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House and Peter Weir’s film Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Winterson, one of Britain’s most celebrated and daring writers, opens her collection with a concise history of ghosts and ghost stories. The latter, she wittily notes, are so often set in earlier times because “ghosts prefer the past. That’s when they were alive”. As in her recent novel Frankissstein, she also speculates that artificial intelligence may now be redefining what it means to be alive or dead. Does our consciousness, in fact, still need materiality? In the future, reflects Winterson, we may regularly discard our worn-out corporeal forms but never really die: Science will temporarily upload our minds, then download them into new bodies. Some people may even prefer pure consciousness and never return to sullied flesh. Wouldn’t they, in effect, have essentially become ghosts?

Some of Winterson’s stories explore these notions, but in No Ghost Ghost Story, she movingly re-creates the grief felt by the surviving member of a couple, haunted by the memory of his beloved.

In The Undiscovered Country, the virtuoso Winterson allows the dead man’s ghost to describe his new condition even as he tries to comfort his bereft partner.

While these two hinged stories are distinctly “literary”, rest assured that Winterson can also elicit more visceral thrills, as in the title story, Night Side of the River, about a young professional woman who finds herself inexorably guided toward the Thames by a pale young man who is very, very wet.

Unlike Winterson, whose many works include the powerful, historically grounded witchcraft novella The Daylight Gate, Paul is virtually unknown. She led a reclusive life, wrote 11 strange, off-kilter novels and was quickly forgotten after her death in 1973 (she was struck by a motorcycle while crossing the street). But her fiction is now being rediscovered, so much so that first editions of her books sell for hundreds of dollars. One can only hope that Twice Lost will be the first of many reissues.

Winterson’s stories and Paul’s haunting novel are excellent contemporary examples of how often women have made supernatural fiction their own, using the form to explore marital discord, societal oppression and psychological distress, as in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Eveline’s Visitant, Margaret Oliphant’s The Library Window, Marjorie Bowen’s Florence Flannery and Ellen Glasgow’s The Shadowy Third. Surely, too, there is no finer contemporary writer in the Gothic mode than Joyce Carol Oates. As it happens, Oates’ recent collection The Ruins of Contracoeur and Other Presences carries an introduction by Lisa Tuttle, whose own distinguished career as a writer of horror and dark fantasy is being doubly honoured this fall: New York Review Books has just brought out her short novel My Death, while Valancourt Books has assembled some of Tuttle’s best stories in Riding the Nightmare, enthusiastically introduced by Neil Gaiman. – Michael Dirda