Ron Charles

THE WASHINGTON POST – A few weeks ago, I noticed water pooling in our basement.

Ever the optimist, I pretended it was just rain leaking in, but then I saw toilet paper floating by.

It could have been worse. Real estate, after all, is the foundation of gothic horror.

From the Castle of Otranto to the House of Usher to those abandoned buildings that you should definitely not investigate at night, the call is always coming from inside the house!

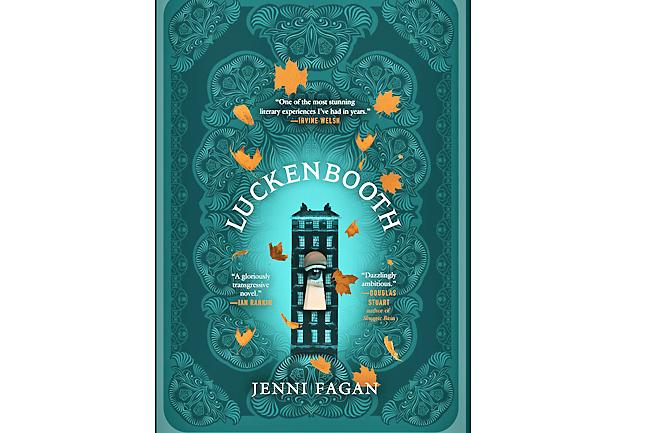

That warning is true for Jenni Fagan’s deliciously weird new novel, Luckenbooth. As this Scottish author did in her unnerving debut, The Panopticon, and her dystopic follow-up, The Sunlight Pilgrims, Fagan once again examines the way people are affected by unhealthy spaces.

Having survived the state care system that bounced her among dozens of homes, she writes about placement and displacement with an arresting mix of insight and passion.

Luckenbooth starts in 1910 and then creeps across the 20th Century on cloven feet.

In the opening section, a poor young woman named Jessie MacRae says goodbye to her father’s corpse and rows across the North Sea in a coffin.

“How buoyant such a thing can be,” she says, but buoyancy is not my first concern here.

Clearly, she’s leaving behind a rather troubled (and thoroughly dead) family.

Among her various complaints, Jessie claims her father is the devil, but all teenagers gripe about their folks, right? Right?

For Jessie, being misunderstood is a common experience.

“I’m like the girl in the story who lets toads fall from her mouth but others think they are pearls,” she says.

Indeed, in Luckenbooth, the membrane between reality and nightmare is so porous that one is constantly tempted to second-guess the implications and discount the horror.

But that can’t cloak Fagan’s mischief for long.

Arriving in Edinburgh – the fantastical Scottish capital that has long shimmered with ectoplasm – Jessie hides her seafaring coffin and ventures cautiously into town.

“They could find so many reasons to hang me,” she worries. “The thing is to try and look like a woman.”

Ducking behind some barrels, she changes into a nice dress, applies a little Vaseline to her lips and combs her hair.

“I must perfectly hide the sharp tip of my horns.”

Apparently, these are no ordinary split ends.

Jessie is on her way to Number 10 Luckenbooth, a nine-storey building near Edinburgh Castle.

Folks on the street tell her that nobody can ever find it, but Jessie will soon have the opposite problem: She can never leave it.

We quickly learn that Jessie has been “sold” by her father to the building’s wealthy owner, a minister of culture named Mr Udnam.

He and his fiancee, Elise, intend to use Jessie as a partner and as a surrogate mother.

For some reason, Elise cannot bear a child herself, perhaps because she’s a suffragette – or a witch.

“We will raise the infant with no knowledge of who you are,” Mr Udnam tells Jessie. “You will not approach the child if you see it in the street. You won’t speak to us again afterwards.”

Ah, the best laid plans!

It never seems to occur to Mr Udnam that Jessie’s father may have had his own reason for selling his daughter into this peculiar arrangement – and it had nothing to do with money.

But Mr Udnam, a fine representative of Edinburgh’s “vampiric soul”, is not used to paying attention to others’ desires or motives.

He’s an oily Dickensian fiend, who “has the serenity of a man entirely without conscience”. Fagan draws him in striking snippets of menace.

About town, he proclaims himself a humble standard-bearer of morality and generosity.

But within the confines of Number 10 Luckenbooth, he’s a monster, and early in the story, he commits an act so heinous that it haunts his cherished building for the next 90 years.

How that haunting is experienced over the decades becomes the subject of subsequent chapters involving a rotating collection of troubled characters.

We encounter costume parties, seances and murders. Fagan tests each floor of Number 10 Luckenbooth as though she’s playing a literary version of Jenga, drawing out one block after another from this unstable structure.

On one floor, a medium tries to make an honest living in a career crowded with frauds. During World War II, a young woman hopes to avenge her brother’s death by becoming a spy. And for a period, the poet William Burroughs takes refuge at Luckenbooth.

Among the most fascinating characters is a young Black man from New Orleans studying bones at the nearby veterinary college.

He knows the city’s history of medical research is clouded with rumours of murder and body snatching, and all that ominous energy seems to be focussed on his apartment building.

“Something in this place is getting to me,” he writes to his brother back home. “Some kind of siren is calling to me. I can feel her in Number 10 Luckenbooth Close. Each night as I go to sleep it feels like I am being lured out to the rocks by her singing. I have begun to do things without thinking.”

As strangely insular as these goings-on are, Luckenbooth never loses its connection to the evolving world outside the building.

We see the scars from wars in Europe, we hear the cries against Margaret Thatcher’s wrenching transformation of the United Kingdom, and through every era we witness how women are exploited.

“Number 10 Luckenbooth,” Fagan writes, “has some kind of purple memory vibrating through it like an endless hum.” But it’s not so much a hum as a muffled scream – with a feral melody and a thundering bass line. Her prose has never been more cinematic.

This story’s inexorable acceleration and its crafty use of suggestion and elision demonstrate the special effects that the best writers can brew up without a single line of Hollywood software – just paper, ink and ghosts.