KABUL (AFP) – One after the other, quickly, carefully, keeping their heads down, a group of Afghan women step into a small Kabul apartment block – risking their lives as a nascent resistance against the Taleban.

They come together to plan their next stand against the hardline regime, which took back power in Afghanistan in August and stripped them of their dreams.

At first, there were no more than 15 activists in this group, mostly women in their 20s who already knew each other.

Now there is a network of dozens of women – once students, teachers or non-government organisation (NGO) workers, as well as housewives – that have worked in secret to organise protests over the past six months.

“I asked myself why not join them instead of staying at home, depressed, thinking of all that we lost,” a 20-year-old protester, who asked not to be named, told AFP.

They know such a challenge to the new authorities may cost them everything: four of their comrades have already been seized.

But those that remain are determined to battle on.

When the Taleban first ruled Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001, they became notorious for human rights abuses, with women mostly confined to their homes.

Now back in government and despite promising softer rule, they are cracking down on women’s freedoms once again.

There is enforced segregation in most workplaces, leading many employers to fire female staff and women are barred from key public sector jobs.

Many girls’ secondary schools have closed, and university curriculums are being revised to reflect their hardline interpretation of religion.

Haunted by memories of the last Taleban regime, some Afghan women are too frightened to venture out or are pressured by their families to remain at home.

For mother-of four Shala, who asked AFP to only use her first name, a return to such female confinement is her biggest fear.

A former government employee, her job has already been taken from her, so now she helps organise the resistance and sometimes sneaks out at night to paint graffiti slogans such as ‘Long Live Equality’ across the walls of the nation’s capital.

“I just want to be an example for young women, to show them that I will not give up the fight,” she explained.

The Taleban could harm her family, but Shala said her husband supports what she is doing and her children are learning from her defiance – at home they practise chants demanding education.

AFP journalists attended two of the group’s gatherings in January.

Despite the risk of being arrested and taken by the Taleban, or shunned by their families and society more than 40 women came to one event.

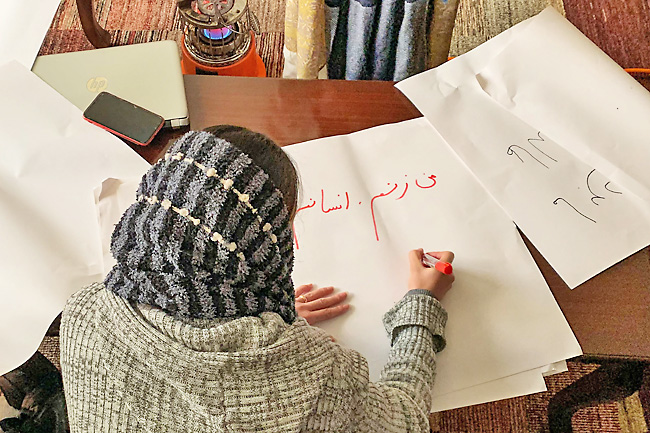

At another meeting, a few women were fervently preparing for their next protest. One activist designed a banner demanding justice, a mobilephone in one hand and her pen in the other.

“These are our only weapons,” she said.

A 24-year-old, who asked not to be named, helped brainstorm ideas for attracting the world’s attention.

“It’s dangerous but we have no other way. We have to accept that our path is fraught with challenges,” she insisted.

Like others, she stood up to her conservative family, including an uncle who threw away her books to keep her from learning.

“I don’t want to let fear control me and prevent me from speaking and telling the truth,” she insisted.

Allowing people to join their ranks is a meticulous process.

Hoda Khamosh, a published poet and former NGO worker who organised workshops to help empower women, is tasked with ensuring newcomers can be trusted.

One test she sets is to ask them to prepare banners or slogans at short notice – she can sense passion for the cause from women who deliver quickly.

Other tests yield even clearer results. Hoda recounts the time they gave a potential activist a fake date and time for a demonstration.

The Taleban turned up ahead of the supposed protest, and all contact was cut with the woman suspected of tipping off officials.

A core group of the activists use a dedicated phone number to coordinate on the day of a protest. That number is later disconnected to ensure it is not being tracked.

“We usually carry an extra scarf or an extra dress. When the demonstration is over, we change our clothes so we cannot be recognised,” Hoda explained.

She has changed her phone number several times and her husband had received threats.

“We could still be harmed, it’s exhausting. But all we can do is persevere,” she added.

The activist was one of a few women flown to Norway to meet face-to-face with the Taleban’s leadership last month, alongside other civil society members, when the first talks on European soil were held between the West and Afghanistan’s new government.

In the 20 years since the Taleban last held power, a generation of women – largely in major cities – became business owners, studied Phds, and held government positions.

The battle to defend those gains requires defiance.

On protest days, women turn up in twos or threes, waiting outside shops as if they are ordinary shoppers, then at the last minute rush together: some 20 people chanting as they unfurl their banners.

Swiftly, and inevitably, the Taleban’s armed fighters surround them – sometimes holding them back, other times screaming and pointing guns to scare the women away.

One activist recalled slapping a fighter in the face, while another led protest chants despite a masked gunman pointing his weapon at her.

But it is becoming increasingly dangerous to protest as authorities crack down on dissent.

A few days after the planning meeting attended by AFP, Taleban fighters used pepper spray on the resistance demonstrators for the first time, angry as the group had painted a white burqa red to reject wearing the all-covering dress.

Activists said two of the women who took part in the protests – Tamana Zaryabi Paryani and Parwana Ibrahimkhel – were later rounded up in a series of night raids on January 19.

Shortly before she was taken, footage of Paryani was shared on social media showing her in distress, warning of Taleban fighters at her door. In the video, Tamana calls out: “Kindly help! Taleban have come to our home in Parwan 2. My sisters are at home.”

It shows her telling the men behind the door: “If you want to talk, we’ll talk tomorrow. I cannot meet you in the night with these girls. I don’t want to (open the door)… Please! help, help!”

Several women interviewed by AFP before the raids, who spoke of “non-stop threats”, have since gone into hiding.

Taleban government spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid denied any women were being held, but said authorities had the right “to arrest and detain dissidents or those who break the law”, after the government banned unsanctioned protests soon after coming to power.

Three weeks on and they have still not been found, with the United Nations (UN) and Human Rights Watch among those calling on the Taleban to investigate the disappearances.

The UN has also demanded information about two more female activists allegedly detained last week, named by rights advocates as Zahra Mohammadi and Mursal Ayar.

The women are learning to adapt quickly. When they began the movement last September, demonstrations would end as soon as one of the participants was pushed or threatened by the Taleban. Hoda said they have now developed a system where two activists take care of the victim, allowing the others – and the protest – to continue.

As the Taleban prevents media coverage of protests, many of the female activists use high quality phones to take photos and videos to post on social media.

The content, often featuring them defiantly showing their faces, can then reach an international audience.

“These women… had to create something from scratch,” said Heather Barr of Human Rights Watch. “There are a lot of very experienced women activists who have been working in Afghanistan for many years… but almost all of them left after August 15.”

“(The Taleban) don’t tolerate dissent. They have beaten other protesters, they have beaten journalists who cover the protests, very brutally. They’ve gone and looked for protesters and protest organisers afterwards,” she added.

Barr believes it is “almost certain” those involved with this new resistance will experience harm.

A separate, smaller woman’s group is now trying to focus on protest that avoids direct confrontation with the Taleban.

“When I am out on the streets my heart and body shake,” said Wahida Amiri. The 33-year-old used to work as a librarian. Sharp and articulate, she is used to fighting for justice having previously campaigned against corruption in the previous government.

Now that is no longer possible, she sometimes meets a small circle of friends in the safety of their homes, where they film of themselves holding candlelit vigils and raising banners demanding the right to education and work.

They write articles and attend debates on audio apps Clubhouse or Twitter, hoping social media will show the world their story.

“I have never worked as hard as I have in the past five months,” she said.

Hoda’s biggest dream was to be Afghanistan’s president, and it’s difficult for her to accept that her political work is now limited.

“If we do not fight for our future today, Afghan history will repeat itself,” the 26-year-old told AFP from her home.

“If we do not get our rights we will end up stuck at home, between four walls. This is something we cannot tolerate,” she said.

Kabul’s resistance is not alone. There have been small, scattered protests by women in other Afghan cities, including Bamiyan, Herat and Mazar-i-Sharif.

“(The Taleban) have erased us from society and politics,” Amiri said.

“We may not succeed. All we want is to keep the voice of justice raised high, and instead of five women, we want thousands to join us.”