SEOUL (ANN/THE KOREA HERALD) – As society undergoes profound transformations driven by cutting-edge technologies, conflicting visions of utopia and dystopia often emerge. Last year’s fervent discourse on generative AI serves as a noteworthy illustration.

To cultivate a unique perspective, consider turning to the artists of our era—explorers who keenly observe and dissect the contemporary fabric of our world through an “anthropological” lens.

In this realm, a distinctive cohort of spirited Korean artists captures attention. Nurtured in the digital age and wielding technological prowess, they boldly venture into uncharted territories of moving images that challenge traditional artistic classifications.

You may have come across the name TZUSOO in the music video of Korean pop legend Cho Yong-pil.

Born in Korea in 1992, the Berlin-based artist runs Studio Princess Computer, which produces animation-style music videos based on 3-D game engines and AI systems. Her pleasurable and somewhat hallucinatory video aesthetics are fundamentally derived from her ontological concerns with virtual beings.

In TZUSOO’s universe, a “virtual” world is not something on which a “real” world is projected. The former is real, on the same footing with the latter. She does not presume a crystal-clear divide between the worlds, and dives into their shifting energy.

She is preoccupied with how a disembodied life is lived on the screen, whose surface generates new flows and forms of engagement in quite different ways from the past. She playfully mobilises technological applications to create animated figures and to lend an impetus to their social life, in conjunction with, and independently from her own.

Some of her works have much to do with her desire to have a baby. And technology for her is not scientific apparatus or machinery per se, but entities that could give “birth.”

Her 3-channel video installation, “Schrodinger’s Baby” (2019/20), whose title comes from physicist Erwin Schrodinger’s hypothetical cat residing inside the box of quantum superposition, takes the form of triptych.

It shows a foetus at four weeks, eight weeks and 16 weeks, with the sounds recorded directly from the artist’s own body parts including her womb.

TZUSOO’s baby as a digital being develops from embryo to foetus in the space the artist constructed, where different possibilities of its identity are presented in parallel. The on-screen virtual space overlaps with the womb, but the baby’s hypnotic movements loaded with symbolism about life and death, evoke an otherworldly atmosphere, due to TZUSOO’s choreographic composition of sequences.

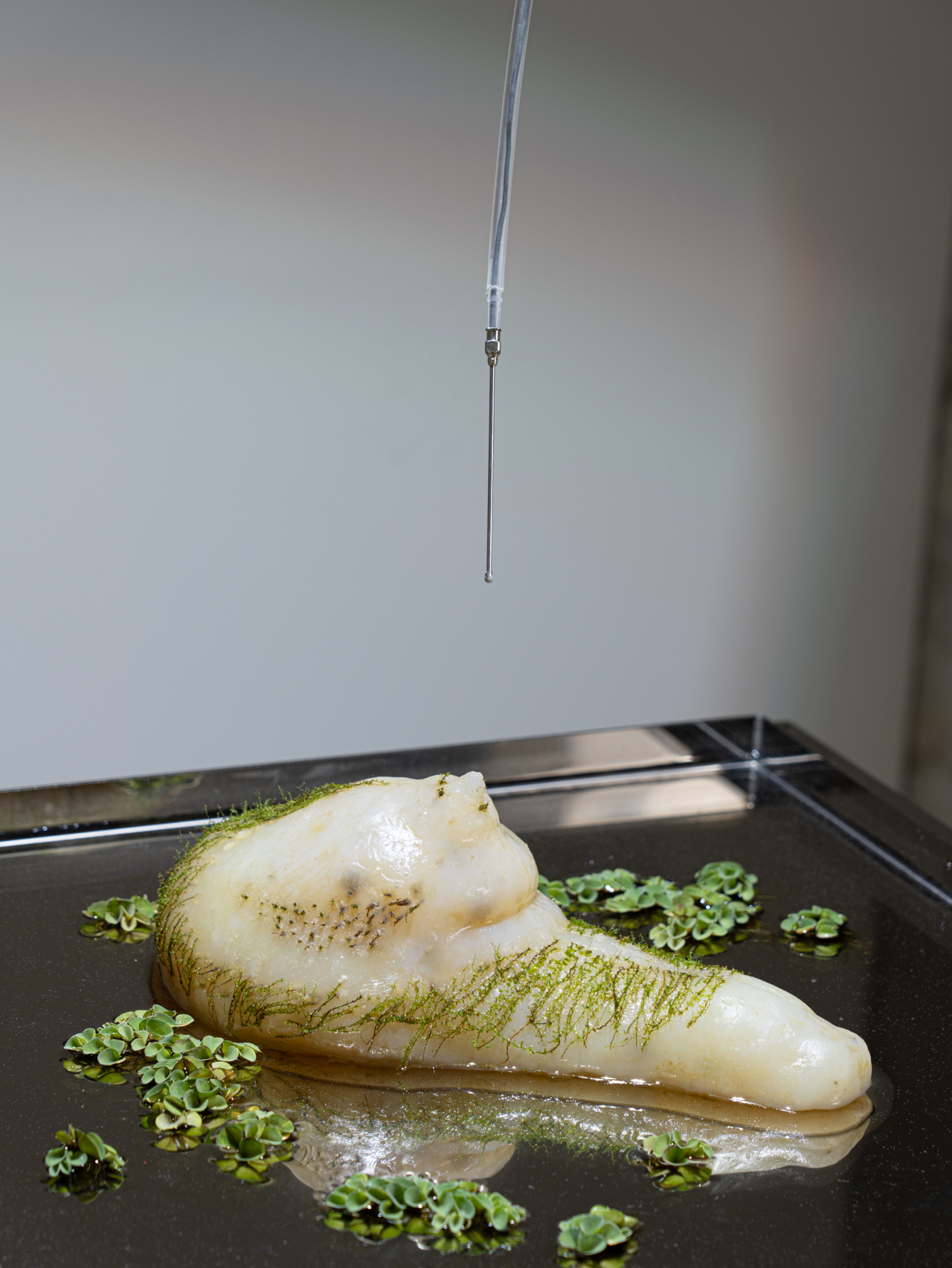

Different in formal terms but consistent in conceptual pursuits, her latest Agarmon series (2023) consists of a sculptural agar-and-moss installation and spray paintings on canvas.

Agarmon is a species of monster-like creature alluding to the baby, “aga” in Korean, that was born at the visceral moment of an orgasm, or when “entropy” is high, according to the artist.

To put it cybernetically, the driving force behind Agarmon’s birth is akin to the state of highest impurity and indeterminacy in the digital realm of information technology.

In 2021, in response to the proposition of AI record label Enterarts, TZUSOO created AI singer-songwriter Aimy Moon. In fact, Aimy has a dual identity.

Seemingly a stunning K-pop star, she has written and produced dozens of songs, and performs them in video, ending up a virtual influencer. Her social media channels release music tracks as well as “The Origin Myth of Aimy Moon” episodes (2021).

In the visual art scene, however, Aimy is a virtual activist, genderless and melancholic.

Among the video series featuring the activist Aimy is “The Cyborg Manifesto (2021),” where it recites excerpts of Donna Haraway’s 1985 seminal essay “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” It argues for breaking away from the hierarchical orders of men, women, animals and machines.

In an era where screens enmeshed in the media infrastructure are almost embedded in our bodily constitution, the boundary of “self” becomes porous. TZUSOO makes an anomalous, amorphous link between the digital and the material, engaging with different selves of her own, and also with the companions to whom she gave birth, but who are not necessarily her avatars.

Her artistic imaginations relate to a fluid notion of humanness and otherness, constantly negotiated in the immensely networked, data-driven world we live in today. This may be called a cybernetic vision of life the artist renders before us.