AFP – Mashudu Mashau said it takes about two minutes to catch a penguin, a task he does weekly to investigate sightings of injured or sickly seabirds.

“We don’t rush… we go down, sometimes we crawl, so that we don’t look threatening, and when we’re close, we aim for the head, hold it and secure the penguin,” the 41-year-old ranger told AFP.

Sometimes, when penguins waddle up from South Africa’s coastline onto nearby streets and hide under cars, it is more of a struggle.

“We had one today. They’re not easy to catch because they go from one side to the other side (of the car), but we got it,” said Mashau, who has dedicated the past eight years to working to protect the species.

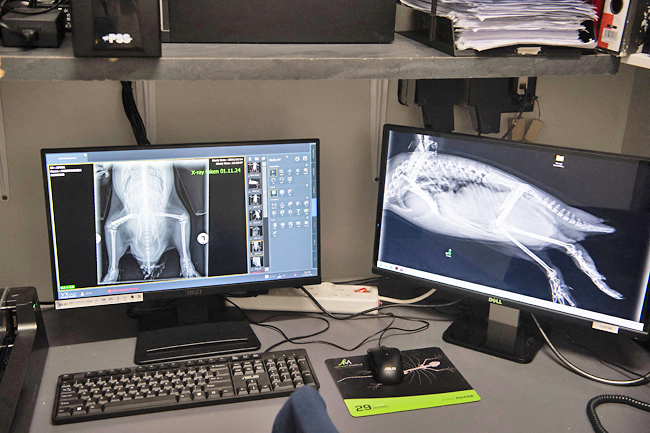

Once caught and placed with care into a cardboard box, the small feathered animals are sent to a specialist hospital for treatment.

But conservationists and veterinarians are worried their efforts aren’t sufficient to stop the decline of the African Penguin, listed as critically endangered last month by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“No matter how much we do, if there isn’t a healthy environment for them, our work is in vain,” said veterinarian David Roberts, who works at the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (SANCCOB) hospital.

Fewer than 10,000 breeding pairs are left globally, mainly in South Africa, down from 42,500 in 1991, and they could become extinct in the wild by 2035, the BirdLife NGO said.

The dwindling numbers are due to a combination of factors including a lack of food, climate change, disturbances, predators, disease, oil spills and more.

But the biggest threat is nutrition, said marine biologist with the South African National Parks Allison Kock.

“So many of the penguins are starving and are not getting enough food to breed successfully,” she told AFP. When penguins do not eat enough, preferably sardines or anchovies, they tend to abandon breeding.

Authorities have imposed a commercial fishing ban around six penguin colonies for 10 years starting in January.

But SANCCOB and BirdLife say the no-fishing zones are not large enough to have a significant impact, and have sued the environment minister over the issue.

“Ideally we would want more fish in the ocean but we cannot control that. What we can ask for, is to limit direct competition for the remaining fish between the industrial fisheries and the penguins,” SANCCOB research manager Katta Ludynia told AFP.

The South African Pelagic Fishing Industry Association said the impact of the fishing industry on penguin food sources is just a small fraction.

“There are clearly other factors that have significant negative impact on the population of the African Penguin,” chairperson Mike Copeland said.

The environment ministry has proposed a discussion group “to resolve the complex issues”, a spokesperson said. While a court hearing is scheduled for March 2025, the minister – only in the post since July – has called for an out-of-court settlement.

Apart from the no-fishing zones, many other initiatives are underway to save the African Penguin, including artificial nests and new colonies.

Being labelled “critically endangered” can be a double-edged sword.