Candice Choi

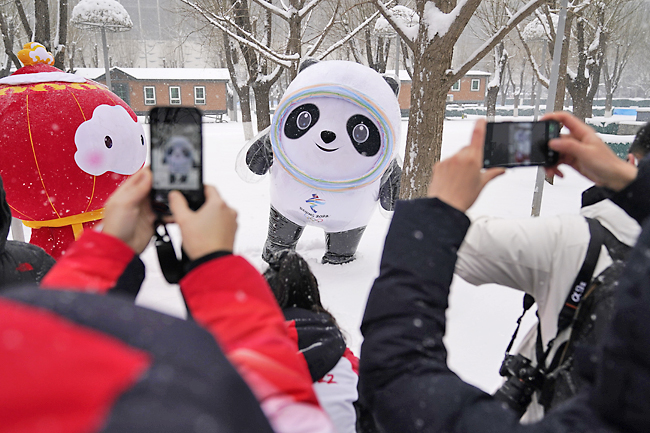

BEIJING (AP) – The panda mascot of the Beijing Games has been a huge success here in the Chinese capital, where fans have lined up for hours to buy plush dolls of the round cartoon, Bing Dwen Dwen.

Then last week, the character appeared on Chinese TV – and horrified viewers by speaking with a grown man’s voice.

“I don’t think it’s cute anymore,” one commenter said on Chinese social media. “It’s just an old man.”

The incident was a minor blemish on the character’s popularity; by week’s end, with the close of the Games approaching, the cult of Bing Dwen Dwen – one of the more ubiquitous Olympics mascots of recent years – was still going strong and drawing long lines for purchases. But it marked the latest comic mishap in the pantheon of Olympic characters.

The notion of a character as a representative of – and a distillation of – a product or event has a long and rich history across the world. In Asia, the creativity is widespread: Packaged goods are brimming with various colourful and cartoonish spokesanimals, spokesfoods and spokesfruits.

In an Olympics context, mascot characters are supposed to embody the culture of their host cities and fuel interest in the event through the merchandising of toys and other memorabilia. But they aren’t always a sure-fire hit. And at times, they’ve been downright polarising.

At the Sydney Games in 2000, for example, an unathletic character named Fatso the Wombat became a rebuke to the wholesome images of the official mascots. At the London Games in 2010, a newspaper likened the one-eyed mascots to “Cyclopean nightmares”.

But the most widely ridiculed mascot may have been at the Atlanta Games in 1996, which featured a cross-eyed blue character that was supposed to represent “information technology” and the city’s ambitions as a technology hub. The creation was introduced at the passing of the torch to Atlanta at the end of the Barcelona Games, when a giant costumed character ran onto the stage to awkwardly join a dance routine.

“He’s in these light blue tights, and the blob body sits way up high, so there’s a lot of leg,” said Sarah Dylla, who curated an exhibit of the Games at the Atlanta History Center.

The character’s name – ‘WhatIzIt’ – deepened the audience confusion because it seemed like a question, but nobody knew the answer, Dylla said.

“It’s an embarrassment is what it is,” declared a review by Catherine Fox, an art critic at an Atlanta paper.

The character was subsequently tweaked and renamed Izzy. Despite the media mockery, Dylla said Izzy proved popular among children and that his non-sensical being might have paved the way for other cartoon characters, including another divisive mascot: Wenlock, from the London Games in 2012.

According to Olympic organisers, Wenlock was supposed to be made from the steel used to build London’s Olympic Stadium, and the giant eye on his face was the “lens of a camera, filming everything he sees”. Some found the appearance unsettling; the Guardian called Wenlock and his look-alike mascot for the Paralympics “by far the worst mascots of any Olympics”.

Opting for more conventional characters hasn’t guaranteed success either, however.

After organisers of the Sydney Games in 2000 selected a trio of cartoon animals representing Australia, the mascots ended up being outshined by a big-bottomed character named Fatso the Wombat that rose to popularity on an Australian comedy show.

Fatso got so popular that athletes carried him to the podium at medal ceremonies, and Olympic officials were asked at a press conference whether he was “stealing the show” and if they were moving to ban him.

“I’m not aware of banning Fatso,” an Olympic official responded.

Despite the embarrassment they can sometimes cause Olympic organisers, mascots have nevertheless become an important way for host cities to put their stamp on the Games and widen the appeal of the event.

And though the mascots typically vanish soon after the Olympics end, it’s their temporary existence that can fuel buying frenzies for souvenirs, particularly among attendees who want mementos of their experience, said Marketing Professor Keith Niedermeier at Indiana University.

“They’re wildly collectible,” he said.

That has been true of Bing Dwen Dwen, which (not who!) has gotten a big publicity boost at medal ceremonies where athletes are given a doll of the bear to hold on the podium. Yet the superstar panda didn’t get through the Games unscathed.

During a news segment on Chinese state TV last week, the mascot was seen bouncing around while interviewing a Chinese free skier.

The voice that emerged from the bear was of an adult man, creating a jarring effect. A reporter was later shown emerging from inside the costume, but the backlash on Chinese social media was swift.

“It was a middle-aged man inside Bing Dwen Dwen. I’m horrified,” one user wrote.

The hashtag “#BingDwenDwenHasSpoken” began trending, prompting Chinese officials to ban it, as they often do with grassroots expressions with any whiff of controversial sentiment.

Beijing Olympic organisers clarified on their social media account that the character on TV was an impostor – and clarified in an e-mail that the “real” Bing Dwen Dwen isn’t able to speak.

The episode doesn’t appear to have dampened the panda’s popularity. On Saturday, the wait to get into the shop selling Bing Dwen Dwen toys in the main media centre was still hours long.