Michael Dirda

THE WASHINGTON POST – Let it snow! When the weather outside is frightful, it’s time for classic ghost stories and mysteries – even if you’re only wrapping them up as presents for lucky friends and family. Need a few ideas? Just read on.

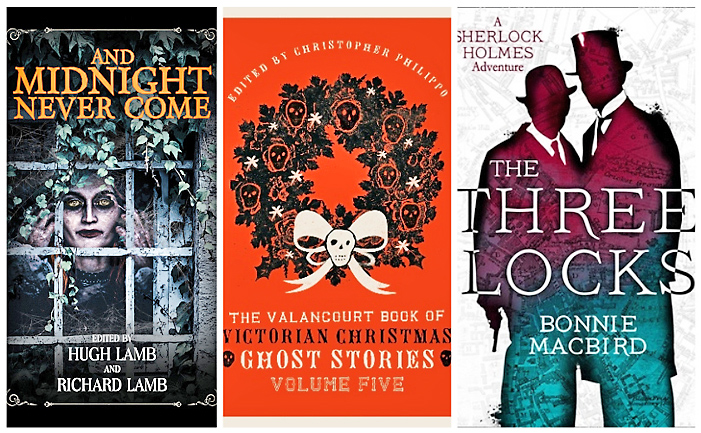

This latest in an annual series again demonstrates that chills and frights still linger in the browning pages of old magazines and Christmas albums. Philippo reprints two fine tales I’ve read elsewhere – Amelia B Edwards’ My Brother’s Ghost Story and Barry Pain’s The Undying Thing – but all his other choices were unfamiliar to me. Since James Skipp Borlase is represented by two stories, I decided to read them first.

The Dead Hand – subtitled A Tale of a Weird and Awful Christmastide – focusses on a smitten housemaid, her unscrupulous lover and a dead Catholic priest’s mummified hand. After being “borrowed” for “a wicked and nefarious purpose”, that bony appendage takes to restless, nocturnal wanderings, periodically bursting out of its sarcophagus to “creep down the wall like a great brown spider”, before scurrying – “flop, flop, flop” – toward an unfortunate sleeper.

In The Wicked Lady Howard a luxury-addicted young beauty marries for money and position. But racked with longing and jealousy, her former lover angrily threatens the new husband with death “during the happiest hour of your life!” This duly comes to pass, but matters then take an eerie, unexpected turn.

The late Hugh Lamb’s anthologies – Victorian Nightmares, Terror by Gaslight and a dozen others – are treasured by aficionados of the weird, in part for Lamb’s informative introductions to each story. This fall, Richard Lamb discovered that his father’s papers comprised enough unused material to make up this posthumous collection, a typical Lambian assortment of writers who are forgotten (F Sartin Pilleau, ER Suffling), half-forgotten (Hume Nisbet, Alice Perrin) and vaguely familiar (William Hope Hodgson).

In Waxworks, by André de Lorde, a debonair young man who claims to be without fear, agrees to pass the night alone in a wax museum. This is never a good idea. In Behind the Wall, by Violet Jacob, a pair of staring eyes, glimpsed through a chink in some ancient masonry, presages a wronged – and long dead – woman’s revenge: “You’ve kept me here for twenty years, but you won’t be able to keep me back – not then. I’ll come for you.”

Beautifully designed, this two-volume set will likely elicit considerable mental consternation.

While the little angel perched on your right shoulder chirps, “The perfect present,” that impish red devil on your left will snakily hiss, “Keep it yourself. You know you want to.”

Luckily, whatever you decide will leave someone extremely happy.

After all, Onions wrote numerous excellent stories besides his two anthology stand-outs: The Beckoning Fair One – a rival to Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw in its hallucinatory power – and lo (The Lost Thyrsus), very much the British analogue to Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s feminist classic, The Yellow Wallpaper.

In Onions’ story a fragile, bedridden young woman starts to hear, at first only faintly, the intoxicating sounds of Dionysian revelry.

After Dickens, Chesterton – the apostle of tradition, paradox and joie de vivre – seems the most Christmas-y of writers, and yet he’s far more than a literary Kriss Kringle. There’s ambiguity and darkness at the heart of his Christian bonhomie, as John C Tibbetts shows in his astute survey of the writer’s weird tales, mysteries and science fiction.

Both critical and anecdotal, this multifaceted appreciation underscores the widespread influence of The Man Who Was Thursday, the Father Brown “impossible crime” stories and the larger-than-life author himself on, among others, John Dickson Carr, Jorge Luis Borges, Ray Bradbury and Neil Gaiman. Tibbetts even appends a history of the Ignatius Press, which brought nearly all of Chesterton’s voluminous writing back into print.

Looking for “a seasonal tale of tradition, family, and murder?” Of course, you are. In this ingeniously plotted short novel by a two-time Edgar winner, a young librarian is killed and an Army Ranger confesses to the crime. An open-and-shut case, right? Maybe not. As Professor Cameron Winter sifts the evidence, he unearths dire associations with his own disturbing past.

Harry Keating wrote classic mysteries such as The Murder of the Maharajah, reviewed whodunits for the Times of London, served as president of the Detection Club and produced several witty, nonfiction studies, beginning with Murder Must Appetize.

If you’re a devotee of the Inspector Ghote novels or would just like insight into how a major crime writer hustled to cobble together a living, add Sheila Mitchell’s biography of her much-missed writer-husband to your Christmas list.

Finally, you still can’t beat Holmes for the holidays. This year three of the best writers of Sherlockian pastiches, all of them members of The Baker Street Irregulars, brought out new books. In Bonnie MacBird’s The Three Locks (Collins), the great detective must solve a trifecta of mysteries involving a magician’s death, a young woman’s drowning and a sealed silver box. In Nicholas Meyer’s The Return of the Pharaoh (Minotaur), Holmes and Watson encounter archaeologists, murderous violence and eerie doings in early 20th-Century Egypt.

Not least, in Observations by Gaslight (Mysterious Press) Lyndsay Faye relates Stories from the World of Sherlock Holmes. In Faye’s first tale, the novella-length, Adventure of the Stopped Clocks, Mrs Godfrey Nortonbetter known as Irene Adler “of dubious and questionable memory”- again crosses paths with her favourite Baker Street frenemy. Finally, to emulate Dr Watson in The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle, let me wish everyone the compliments of the season. Happy reading to all and to all a good night!