Jocelyn Noveck

NEW YORK (AP) – Even for a legendary film director like Martin Scorsese, the assignment was a daunting one.

Take one of the famous American period rooms at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and make essentially a one-frame movie with no camera: a tableau, not a film, but using your cinematic sensibility. Your actors are mannequins, and the costumes have been chosen for you.

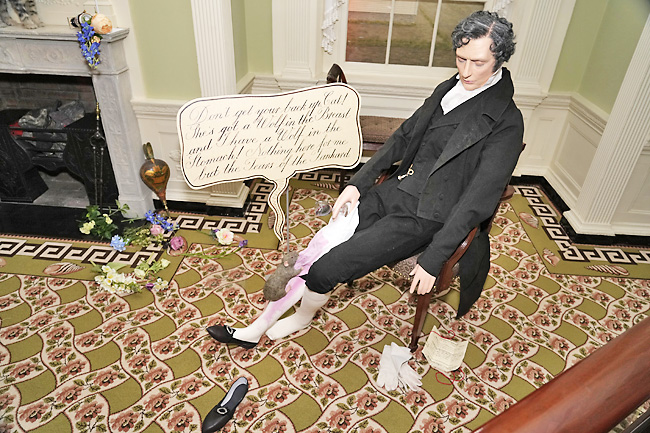

“Create a one-frame movie in a period room? A great opportunity and an intriguing challenge,” the director wrote in a statement next to his creation, a mysterious mix of characters, emotions and fashion in the museum’s striking Frank Lloyd Wright Room.

Eight other directors, including Regina King and Chloé Zhao, are also putting their stamp on the period rooms, for ‘In America: An Anthology of Fashion’, the Met’s spring Costume Institute exhibit launched with Monday’s Met Gala, and officially opening on May 7. Guests at the gala, which raises millions for the self-funding institute and has become a major fashion and pop culture spectacle, will be among the first see the displays.

Also among the first: Jill Biden. The First Lady toured the exhibit at a preview on Monday morning and spoke of how she’s learned, in her current job, that language isn’t the only means of communication – fashion is, too. “We reveal and conceal who we are with symbols and shapes, colours and cuts, and who creates them,” Biden said.

The First Lady spoke of how the history of American design is full of unsung heroes – some of whom the new exhibit is now celebrating, especially women. She also recalled how she sent a message of solidarity with Ukraine by wearing a sunflower appliqué on the blue sleeve of her outfit at the State of the Union address. “Sitting next to the Ukrainian ambassador, I knew that I was sending a message without saying a word,” she said.

The exhibit is the second part of a broader show on American fashion to mark the Costume Institute’s 75th anniversary. Masterminded as usual by star curator Andrew Bolton, the new instalment is both sequel and precursor to ‘In America: A Lexicon of Fashion’, which opened last September and is focussed more on contemporary designers and establishing what Bolton calls a vocabulary for fashion. (The shows will run concurrently and close together in September).

If the new ‘Anthology’ show is meant to provide crucial historical context, it also seeks to find untold stories and overlooked figures in early American fashion, especially female designers, and especially those of colour. Many of their stories, Bolton said when announcing the show, “have been forgotten, overlooked, or relegated to a footnote in the annals of fashion history”.

The nine directors were tapped to enliven the storytelling with their own varying aesthetics. In addition to Scorsese they include two of the Met Gala’s hosts on Monday night – actor-director King and designer-director Tom Ford. Also contributing are Radha Blank, Janicza Bravo, Sofia Coppola, Julie Dash, Autumn de Wilde, and Zhao, last year’s Oscar winner.

For King, the Richmond Room, depicting early 19th-Century domestic life for wealthy Virginians, provided a chance to highlight Black designer Fannie Criss Payne, who was born in the late 1860s to formerly enslaved parents and became a top local dressmaker. She was known for stitching a name tape into her garments to “sign” her work – part of an emerging sense of clothes-making as a creative endeavour. King said she was looking “to portray the power and strength Fannie Criss Payne exudes through her awe-inspiring story and exquisite clothing”, placing her in a prosperous working situation – and proudly wearing her own design – fitting a client, and employing another Black woman as a seamstress.

Filmmaker Blank looks at Maria Hollander, founder of a clothing business in the mid-19th Century in Massachusetts who used her business success to advocate for abolition and women’s rights. In the museum’s Shaker Retiring Room, director Zhao connects with the minimalist aesthetic of 1930s sportswear designer Claire McCardell.

De Wilde uses her set in the Baltimore Dining Room to examine the influence of European fashion on American women – including some disapproving American attitudes about those low-cut gowns from Paris. Dash focusses on Black dressmaker Ann Lowe, who designed future First Lady Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress but was barely recognised for it. “The designer was shrouded in secrecy,” wrote Dash. “Invisibility was the cloak she wore, and yet she persisted.”

In the wing’s Gothic Revival Library, Bravo looks at the works of Elizabeth Hawes, a mid-20th Century designer and fashion writer. And Coppola, given the McKim, Mead & White Stair Hall and another room, wrote that she at first wasn’t sure what to do: “How do you stage a scene without actors or a story?” She ultimately teamed with sculptor Rachel Feinstein to create distinctive faces for her “characters”.