Daphne Kalotay

THE WASHINGTON POST – Each year, among the new fiction collections fighting for attention are a handful published neither through mainstream houses nor the usual small-press alternatives but via a third avenue: book prize contests.

Some of these competitions, such as the AWP Grace Paley Prize, have been around for 40-plus years and rely on coordination with university and indie presses.

Others, such as the Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing, are held by the press itself. Monetary awards can range from USD1,000 to USD15,000, but what all winners share is the challenge, once their collections launch, of being noticed by the public.

With that in mind, here are some of the notable prizewinning collections published in 2022.

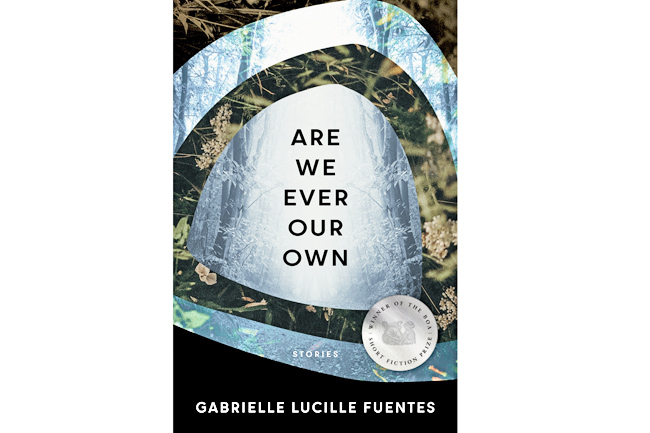

Rich with dreams and ghosts, Gabrielle Lucille Fuentes’s Are We Ever Our Own (BOA Short Fiction Prize) follows descendants of a Cuban family to America and beyond.

Yet its true subject is female artists overshadowed by their male counterparts.

“You say my work is disappearing,” one character wrote in a letter. “Turning in on itself – getting smaller and smaller. You say ‘domestic, tidy, craft.’ You don’t mean ‘craft’ in that nice way the boys upstate with their forged steel boxes do.”

In other stories, Fuentes adopts elegant expository summary that can create emotional distance, but immediacy returns whenever we hear these women’s voices directly.

Palm Chess alternates between a screenplay and journal entries by a female filmmaker who has left her artist husband – movingly connecting the private and creative selves.

There Is Only Us by Zoe Ballering (Katherine Anne Porter Prize in Short Fiction) resides in the realm of speculative fiction.

In the excellent Mothers, an inoculation has “eliminated the biological need for sleep”, dooming the uninoculated to decreased productivity and lower station – raising pertinent questions about how social groups divide based on medical choices.

Whether set on Noah’s ark or at an everyday high school of “pep rallies in which acned cheerleaders performed thigh stands to thunderous applause, early release on Fridays, a vending machine on the second floor that spit back even the crispest dollar bills”, these stories get to the heart of human existence.

If punchy first sentences are to your taste, Wendy Wimmer’s Entry Level (Autumn House Fiction Prize) is the book for you.

“When Mary Ellen’s left breast grew back on its own during our Saturday dinner break, we had confirmation that something weird was happening.”

Many intros seem designed to startle; several stories enter fantastical terrain.

In the delightful Texts From Beyond, a company purportedly helps people send messages to deceased relatives.

Equally affecting are stories more rooted in the real, where Wimmer gets closer to character and emotion, such as Billet-Doux, told via unsent letters addressed to celebrities, random people, inanimate objects, a recurring guy on the BART and the protagonist herself.

Like Wimmer, Erica Plouffe Lazure introduces Proof of Me (New American Fiction Prize) with a shock. Yet Lazure handles such moments with subtlety, in rich Southern cadences.

And while accidents (comic and benign, gruesome and deadly) occur throughout these lightly interconnected stories, Lazure’s tone remains stoically upbeat.

From a professor at the local college to labourers at Golden Poultry and the Gas ‘N’ Sip, Lazure makes the reader game to follow these small towners’ travails. “I am a known heretic in these parts because I mow the lawn on Sundays,” one resident proclaimed.

Even as some venture to San Francisco and beyond, their North Carolina ties remain strong.

Geographical place also centres Toni Ann Johnson’s Light Skin Gone to Waste (Flannery O’Connor Prize for Short Fiction), about a Black family in small-town New York in the 1960s through the mid-aughts: Philip, the complicated psychologist father; his fiercely savvy wife, Velma; and daughter Maddie, chafing at a suburbia where no one looks like her.

As they suffer indignities due to ignorant neighbours – and each other – the prose in Maddie’s sections feels most alive.

Yet the linguistic neutrality of Phil’s sections reflects an academic who, when scorned by bigots, responds calmly with legal warnings. With its constancy of character, this quietly powerful collection leaves the impression of a novel.

Meron Hadero’s exquisite A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times (Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing) includes stories possibly inspired by Hadero’s life (born in Ethiopia, she then moved to Germany and America).

In The Wall, about an intergenerational friendship, and The Suitcase, about a visit to Addis Ababa, small details crystallise whole worlds.

At a busy intersection, “small nimble vehicles, Fiats and VW Bugs, skimmed the periphery of the traffic, then seemed to be flung off centrifugally, almost gleefully, in some random direction”.

Sentences infused with attitude throw gut punches that land with enough power to bring on tears.

Wistful humour illuminates Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me by John Weir (AWP Grace Paley Prize for Short Fiction). Having survived school bullies and the AIDS crisis, the narrator is still processing his grief. He is also very funny.

Delightfully jaded wisdom buoys Louise Marburg’s You Have Reached Your Destination (EastOver Fiction Prize). “We were both in our early forties, and neither of us had been married, which made me a spinster and him a catch.”

Marburg captures how the wounds of childhood linger – yet she allows moments of grace. It is gratifying to read fiction that tackles complex emotions.

In Marburg’s hands, even the seemingly whimsical (two stories involve fortune tellers) carries the weight of truth.

Ramona Reeves’ engrossing It Falls Gently All Around and Other Stories (Drue Heinz Literature Prize) follows two main couples in Mobile, Alabama.

At the hub is Babbie, who has endured a miscarriage and multiple husbands.

Reeves brings poetry to the portrayal of those who have it hard: “Some people had to make do with pushing their noses against the pretty parts of life.” Donnie is a good-natured alcoholic prone to poor decisions and “a bad case of hope”.

Babbie’s first ex-husband and his wife help reveal the nuances of long-term partnership with perception and humour.

Yet it’s small gestures that speak worlds, as when wife and ex-wife hug, “barely touching, a flurry of hand pats on shoulders that stood in for sincerity”.

Frayed relationships populate Christopher Linforth’s The Distortions (Orison Fiction Prize), set in and around Zagreb during and after the Serbo-Croatian War.

Whether between an American professor-slash-womaniser and his student, or a dying male ballet dancer and an older female photographer, intergenerational trauma taints transactions and corrupts intimacy.

These vivid stories remind us how quickly perceived difference can lead to conflict. In “brb” a supposedly 17-year-old boy writes his online American girlfriend: “Croatia is not that different from Florida… Like your Confederates, Chetnik Serbs still curse at us and say we are the aggressor, the destroyer of the Republic.”

That he is really a middle-aged man encapsulates the irony and revelation of The Distortions.