Franklin Briceño & Matt O’Brien

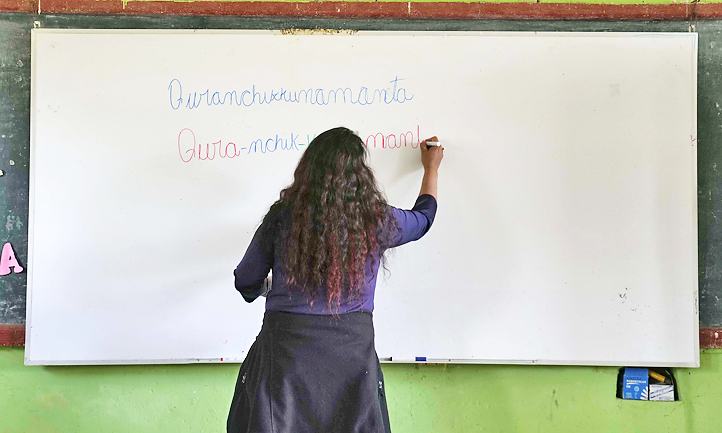

LIMA (AP) – About 10 million people speak Quechua, but trying to automatically translate e-mails and text messages into the most widely spoken Indigenous language family in the Americas was long all but impossible.

That changed on Wednesday, when Google added Quechua and a variety of other languages to its digital translation service.

The Internet giant says new artificial intelligence (AI) technology is enabling it to vastly expand Google Translate’s repertoire of the world’s languages.

It added 24 of them this week, including Quechua and other Indigenous South American languages such as Guarani and Aymara. It is also adding a number of widely spoken African and South Asian languages that have been missing from popular tech products.

“We looked at languages with very large, underserved populations,” Google research scientist Isaac Caswell told reporters.

The news from the California company’s annual I/O technology showcase may be celebrated in many corners of the world. But it will also likely draw criticism from those frustrated by previous tech products that failed to understand the nuances of their language or culture.

Quechua was the lingua franca of the Inca Empire, which stretched from what is now southern Colombia to central Chile. Its status began to decline following the Spanish conquest of Peru more than 400 years ago.

Adding it to the languages recognised by Google is a big victory for Quechua language activists like Luis Illaccanqui, a Peruvian who created the website Qichwa 2.0, which includes dictionaries and resources for learning the language.

“It will help put Quechua and Spanish on the same status,” said Illaccanqui, who was not involved in Google’s project.

Illaccanqui, whose last name in Quechua means “you are the lightning bolt”, said the translator will also help keep the language alive with a new generation of young people and teenagers, “who speak Quechua and Spanish at the same time and are fascinated by social networks.”

Caswell called the news a “very big technological step forward” because until recently, it was not possible to add languages if researchers couldn’t find a big enough trove of online text – such as digital books, newspapers or social media posts – for their AI systems to learn from.

United States (US) tech giants don’t have a great track record of making their language technology work well outside the wealthiest markets, a problem that’s also made it harder for them to detect dangerous misinformation on their platforms. Until this week, Google Translate was offered in European languages like Frisian, Maltese, Icelandic and Corsican – each with fewer than one million speakers – but not East African languages like Oromo and Tigrinya, which have millions of speakers.

The new languages will roll out this week. They won’t yet be understood by Google’s voice assistant, which limits them to text-to-text translations for now. Google said it is working on adding speech recognition and other capabilities, such as being able to translate a sign by pointing a camera at it.

That will be important for largely spoken languages like Quechua, especially in the health field, because many Peruvian doctors and nurses who only speak Spanish work in rural areas and “are unable to understand patients who speak mostly Quechua”, Illaccanqui said.

“The next frontier, or challenge, is to work on speech,” said Arturo Oncevay, a Peruvian machine translation researcher at the University of Edinburgh who co-founded a research coalition to improve Indigenous language technology across the Americas. “The native languages of the Americas are traditionally oral.”

In its announcement, Google cautioned that the quality of translations in the newly added languages “still lags far behind” other languages it supports, such as English, Spanish and German, and noted that the models “will make mistakes and exhibit their own biases”. But the company only added languages if its AI systems met a certain threshold of proficiency, Caswell said.

“If there’s a significant number of cases where it’s very wrong, then we would not include it,” he said. “Even if 90 per cent of the translations are perfect, but 10 per cent are nonsense, that’s a bit too much for us.”

Google said its products now support 133 languages. The latest 24 are the largest single batch to be added since Google incorporated 16 new languages in 2010. What made the expansion possible is what Google is calling a “zero-shot” or “zero-resource” machine translation model – one that learns to translate into another language without ever seeing an example of it.

Facebook and Instagram parent company Meta introduced a similar concept called the Universal Speech Translator last year.

Google’s model works by training a “single gigantic neural AI model” on about 100 data-rich languages, and then applying what it’s learned to hundreds of other languages it doesn’t know, Caswell said.

“Imagine if you’re some big polyglot and then you just start reading novels in another language, you can start to piece together what it could mean based on your knowledge of language in general,” he said. He said the new group ranges from smaller languages like Mizo, spoken in northeastern India by about 800,000 people, to more widely spoken languages like Lingala, spoken by around 45 million people across Central Africa.

It was more than 15 years ago – in 2006 – that Microsoft got some positive attention in South America with a software feature translating familiar Microsoft menus and commands into Quechua. But that was before the current wave of AI advancements in real-time translation.

Harvard University language scholar Américo Mendoza-Mori, who speaks Quechua, said getting Google’s attention brings some needed visibility to the language in places like Peru, where Quechua speakers are still lacking in many public services. The survival of many of these languages “will depend on their use in digital contexts”, he said.

Another language scholar, Roberto Zariquiey, said he’s sceptical that Google could make an effective language revitalisation tool for Quechua, Aymara or Guarani without closer participation from community groups in the region.

“Languages are deeply linked to lives, to cultures, to ethnic groups and political organisations,” said linguist Zariquiey at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. “This should be taken into account.”