ANN/THE STAR – The concept that water is synonymous with life has persisted throughout history.

This belief has motivated inhabitants in specific regions worldwide to build houses on stilts and live on the water. Over generations, natural population growth has led to the expansion of these settlements, evolving them into sprawling floating or water villages.

Presently, such communities thrive in diverse degrees across various Asian countries, including Malaysia, China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Brunei.

Away from the shores, their unique setting and lifestyle, which is apparently different from dwelling on the land, make them an interesting drawcard for savvy travellers. Particularly the one in Brunei, which is touted as the largest water village cluster in the world. Known as Kampong Ayer, this expansive settlement on the Brunei River in the heart of the nation’s capital city, Bandar Seri Begawan, stands today as an emblem of national heritage.

So, I marked it as a “must explore” in my itinerary when I toured this tiny Southeast Asian nation recently.

Officially called Brunei Darussalam, it’s an oil-rich Islamic monarchy led by one of the richest people on Earth. By reading some of those media gossip, the outside world perceives that everything in Brunei is made of gold, from the water taps to the door handles.

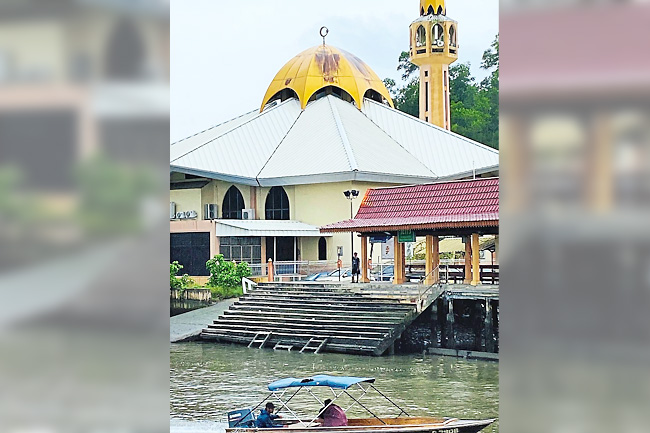

Obviously, it didn’t take me much time to find out that it’s a myth. However, the opulence of the nation came out distinctly when I visited the two significant mosques in the capital: Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Mosque and Jame’ ‘Asr Hassanil Bolkiah. Both the architecturally wondrous creations have multiple domes made from pure gold, and the shimmer from them confirmed my presence on an extraordinarily wealthy land.

Brunei is tucked on the island of Borneo along with the Malaysian states Sabah and Sarawak, and Indonesia’s Kalimantan. The Sultanate has been ruled by Malay Islamic rulers or Sultans since the 14th Century. Historians tout this monarchy as the best fusion of Malay culture with the teachings of Islam, and a mutual respect between the monarch and the people.

The fate of the nation changed in the early 20th Century with the discovery of oil, and very soon it became economically super-giant by selling petroleum products to the rest of the world.

It’s said living on the waters of the Brunei River was conceptualised even before the arrival of the Sultans. The driving reasons for this were the ease of building dwellings on stilts, the convenience of movement along the water in the absence of roads, and the availability of abundant seafood. Fast forward several centuries, and today the settlement is a huge cluster consisting of 42 villages, over 4,000 homes with nearly 40,000 people living there.

In the Bruneian Malay language, kampong means village, and ayer means water. Initially, I thought it to be a small affair on water, surely bigger than what I had seen earlier in Ha Long Bay in Vietnam or Penang in Malaysia. However, I was proven wrong. At first sight from the shoreline, I was awe-struck to see a never-ending stretch of floating houses, and after landing there on one of its several jetties, the domain crowded with a mix of old and new timber and fibre houses flanking a maze of wooden and concrete boardwalks appealed to me more as a floating township than a village.

“It’s a self-contained community with its own mosque, schools, clinics, shops, electricity, clean water and emergency services,” said my guide Mohammed, while showing me around the village.

During the early days, most of the residents were fishermen or boat makers. Now many have jobs or businesses in the capital or other nearby places.

They mainly use the water taxis for transportation, and some even have their own cars parked on the shore.

“However, at the end of the day, they love to come back to their floating home; perhaps they can’t sleep without hearing the sounds of water,” commented Mohammed.

To sense the rhythm of life on the water, I wandered with him along the boardwalks, went past the houses, smelt the aroma of curries from their kitchens floating in the air, watched women hanging the laundry, elderly folks chatting outside a small grocery store, and children playing with the chickens. I visualised an easy-going and simple lifestyle not stained by extreme touches of modernity.

Though my perception changed a little when, as part of our tour, we visited a family home for some hospitality. It was a five-bedroom house fitted with everything that modern generations look for, from satellite television, air conditioning, and 21st-Century kitchen outfits to mobile reception and fast WiFi connection. “This is the beauty of Kampong Ayer.

While from outside it may appear laid back, inside we are up to date with anything modern,” commented Haiji, our host and owner of the house, who has lived in the water village all his life.

“We love the life on the water; we live here as a big family, caring for each other and sharing our joy and sorrow.

“Life on the shore will not give us the kind of fellow feeling and peace we have here,” he said before bidding us goodbye.

When Venetian scholar Antonio Pigafetta visited Kampong Ayer in 1521, he dubbed the place the ‘Venice of the East’, which to me is an over-ambitious exaggeration. However, surely it’s something to be experienced when in Brunei as an example of a national heritage well maintained by the ruler and the subjects. – Sandip Hor