Lyna Mohammad

As the second biggest city after Kota Kinabalu in Sabah, Malaysia, Sandakan is known to Sabahans and tourists alike for its eco-tourism centres, among which are the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, the Turtle Islands Park, the Kinabatangan River and the Gomantong Caves; and for food lovers, seafood will come to mind.

My mother was born and spent several years of her childhood in Sandakan before her family moved to Papar, and later migrated to the Sultanate during the Japanese occupation.

Despite having visited the place a couple of times, I had never got the chance to really explore the nature side of Sandakan nor had I the chance to meet relatives of my mother who reside in the city until my recent trip.

Being her last trip to Sabah before the pandemic, it was not surprising seeing my mother looking forward to see her relatives again.

During our three-day stay, we were hosted by my mother’s cousin, who introduced us to one of the popular tourist spots in Sandakan – the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre.

Orangutans were once found throughout Southeast Asia. However, only a small number can be found in the rainforests of Borneo and Sumatra today.

There are three species of orangutan – Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli. The Bornean we visited is identified by its scientific name of Pongo pygmaeus.

The weather in Sandakan had been unpredictable for the past few weeks. But we were lucky to have the weather in our favour and were just in time to witness the orangutan feeding time.

The 43-square-kilometre site of protected land at the edge of Kabili Sepilok Forest Reserve was turned into a rehabilitation centre for orangutans before it was changed to Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre. It was opened in 1964, and was reported to be the first official orangutan rehabilitation project for rescued orphaned baby orangutans from logging sites.

Some 60-80 orangutans are living independently in the reserve while approximately 25 orphaned ones are housed in the nurseries to help them learn to survive in the wild.

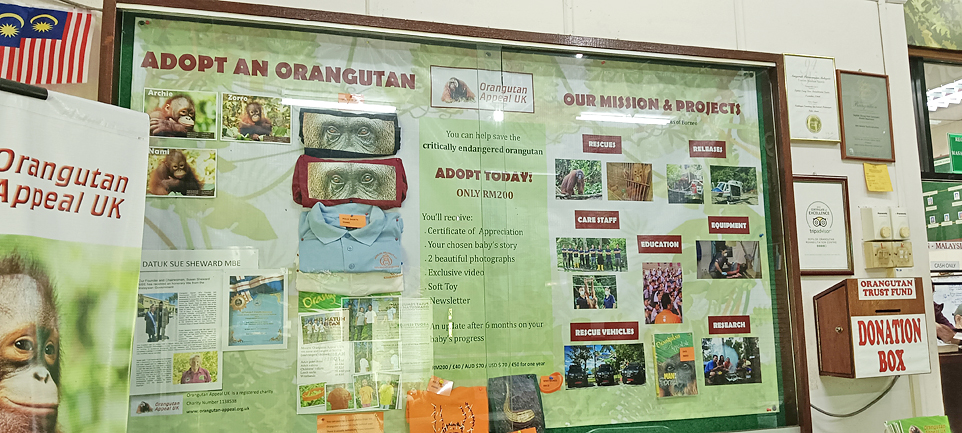

The centre is collaborating with an organisation called Orangutan Appeal UK to introduce the ‘Adopt an Orangutan’ project, a scheme to help raise vital funds.

For orangutan babies to learn the skills they need to survive the wild, they are usually put with their mothers for up to eight years, learning the most important aspect of their survival – climbing trees.

According to the information I gathered during the visit, young orangutans that are kept in captivity often become sick or suffer from neglection issues, while those raised as pets are usually not fit to be released into the wild.

This is where the Sepilok centre comes in to help these orangutans without questions, although it can be an expensive process.

Back to my visit, after getting our tickets, we were advised to leave our bags behind as orangutans are known to grab them.

The walk on the walkway took us about 10 minutes. The surrounding was covered in lush green, forming a sort of shelter from the sun, which made it humid due to the lack of airflow.

There was quite a crowd waiting on the platform, all armed with their cameras and mobile phones.

Within minutes, the feeder came in with a good load of food consisting of corn and green vegetables.

After the signal was made, several orangutans began to arrive from all directions, swinging and jumping from trees to trees down to the feeding platform.

We saw one of them grabbing as much food as it could carry all the way down to its foot, before making its way up the trees.

The crowd giggled, but we were advised to stay as silent as possible as noises would excite the mammals, causing them to approach us.

After the feeding time, visitors had the option to visit the outdoor nursery or enjoy a nature walk.

Although I am not a big fan of wildlife or the jungles, I found the Sepilok visit to be enjoyable and educational, true to its purpose for rehabilitation and education.