LONDON (AP) – European scientists have taken a significant step closer to mastering a technology that could allow them to one day harness nuclear fusion, providing a clean and almost limitless source of energy, British officials said on Wednesday.

Researchers at the Joint European Torus (JET) experiment near Oxford managed to produce a record amount of heat energy over a five-second period, which was the duration of the experiment, the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) said.

The 59 megajoules of sustained fusion energy produced were more than double the previous record achieved in 1997.

The agency said the result was “the clearest demonstration worldwide of the potential for fusion energy to deliver safe and sustainable low-carbon energy”.

“If we can maintain fusion for five seconds, we can do it for five minutes and then five hours as we scale up our operations in future machines,” said Programme Manager for EUROfusion Tony Donne. “This is a big moment for every one of us and the entire fusion community.”

CEO of the UKAEA Ian Chapman said the results were a “huge step closer to conquering one of the biggest scientific and engineering challenges of them all”.

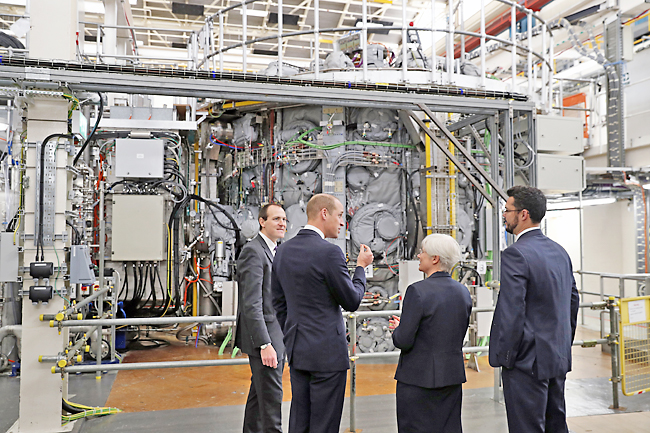

The facility, also known as JET, is home to the world’s largest and most powerful operational tokamak – a donut-shaped device that is considered one promising method for performing controlled fusion.

Scientists who were not involved in the project believed it was a significant result, but still a very long way from achieving commercial fusion power.

Researchers around the world have long been working on nuclear fusion technology, trying different approaches. The ultimate goal is to generate power the way the sun generates heat, by pressing hydrogen atoms so close to each other that they combine into helium, which releases torrents of energy.

Carolyn Kuranz at the University of Michigan called the development “very exciting” and a step toward achieving “ignition”, or when the fuel can continue to “burn” on its own and produce more energy than what’s needed to spark the initial reaction.

She said the results appeared “very promising” for ITER, a much larger experimental fusion facility in southern France that uses the same technology and is backed by many European countries, the United States, China, Japan, India, South Korea and Russia. It is expected to begin operation in 2026.

Fusion expert at the University of Rochester Riccardo Betti said the achievement lay mainly in sustaining the reaction at high performance levels for five seconds, significantly longer than previously achieved in a tokamak.

The amount of power gained was still well below the amount needed to perform the experiment, he added.

An emeritus professor of energy conversion at the University of Newcastle Ian Fells described the new record as a landmark in fusion research. “Now it is up to the engineers to translate this into carbon-free electricity and mitigate the problem of climate change,” he said. “Ten to 20 years could see commercialisation.”

Stephanie Diem of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said the technology used by JET to achieve the result, using magnets to control ultra-hot plasma, show that harnessing fusion – a process that occurs naturally in the stars – is physically feasible.

“The next milestone on the horizon for magnetic fusion is to demonstrate scientific breakeven, where the amount of energy produced from fusion reactions exceeds that going into the device,” she said.

Rival teams are racing to perfect other methods for controlling fusion and have also recently reported significant progress.

Scientists hope that fusion reactors might one day provide a source of emissions-free energy without any of the risks of conventional nuclear power.