Henry Wismayer

THE WASHINGTON POST – “It is midnight on the coast of Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean, two hundred miles south of Java.” It is with this scene – of a million scarlet crabs overrunning a tropical beach like some nightmarish alien swarm – that the doyen of natural history, David Attenborough, begins The Trials of Life.

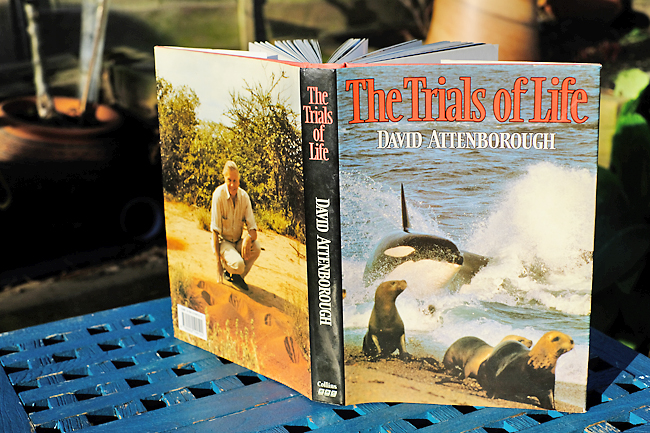

Published in 1990 and designed to accompany the nature documentary series of the same name, it’s a book about animal behaviour, split into chapters – ‘Growing Up’, ‘Home-making’, ‘Friends and Rivals’ – describing different stages of the life cycle.

I suspect I am not alone in supposing that most children’s earliest curiosity about the wider world is sparked not by travel narratives, nor even by adventure fiction, but by factual and reference books.

As a child, I would sit up late into the night and scour atlases and encyclopaedias, wondering at the vast span of the continents and the seemingly endless miracles they contained. I’ve always thought of these fascinations as the building blocks of wanderlust. As adults, we covet travel to rekindle the capacity for wonder we enjoyed when we were young.

When I laid hands on my copy of The Trials of Life, it quickly became a favourite repository of bookish knowledge. I received it in glossy hardback as a gift, and it was my most treasured present, the one that, for days afterward, I carried around with me from room to room like a talisman.

The premise is straightforward. “My concern here is to describe the happenings, rather than the psychological and evolutionary mechanisms that produce them,” Attenborough wrote. It makes no pretensions of analysis or theory. Instead, it reads like a compendium of snapshots, each illuminating some facet of nature’s invention, brutality and evolutionary logic.

The overall effect is to emphasise the impression that every living creature is joined by universal quests for food, shelter and gene perpetuation. The trials, we discover, compel an opossum and Amazon river dolphin in kind. This style, segueing between vignettes, from jungle to desert to pole, echoed the structure of the marquee TV programmes I’d adored, which had run on the BBC on Sunday evenings that fall.

The front cover depicts the moment that people remember. In the foreground, two sea lions lollop up a beach toward the frame, while another looks over its shoulder, apprehending, with what one imagines would be no small horror, that a killer whale has just exploded out of the Atlantic breakers behind them.

Years later, I would visit the Valdes Peninsula in Argentina, where these scenes of orcas beaching themselves to snaffle sea lion pups off the shingle were filmed. Alas, the ingenious pod of killers that has become famous for this unique hunting method were having a day off. (An armadillo did shuffle past and sniff my shoe, which offered some consolation).

The other images, of which there are dozens, almost one for every page of text, are more illustrative than spectacular: a lion cub gnaws on the nose of a dead wildebeest; cleaner wrasse attend to the oral hygiene of a gaping grouper fish; a male garden spider attempts to seduce a giant female by plucking at a strand of silk. By modern standards, many of the photos seem unremarkable, though I found them endlessly enchanting at the time.

Similarly, reading the book now, I’m surprised by how much of it feels dryly observational. Attenborough is a lucid writer and peerless educator.

But there are few writerly flourishes, and certainly none of the personal and anthropomorphic musings that characterise so much nature writing today. There is a whimsical kind of comfort to be found in this simplicity, and the concomitant sense that, in those pre-Internet days, bare facts, plainly told, were enough to fire up the imagination. Perhaps this is my nostalgia talking.

The truth, after all, is that my copy of The Trials was more than the sum of its pictures and words. I distinctly remember that my mum’s bookshelves stored an earlier Attenborough book, Life on Earth. This one was a paperback, and its spine was cracked with use, evidence that it had been a favourite of my dad’s, who had died when I was an infant.

It is no great revelation to suggest that boys who grow up fatherless will seek surrogates in other male role models, both immediate and remote. And I don’t doubt that I saw, in Attenborough, another father figure for the roster. I realised, upon revisiting the book, that I read the words in his inimitable voice.

Perhaps, as much as anything, what I coveted was proximity to him, the great paragon of curiosity. By 1990, when Trials aired, Attenborough had already been knighted and had already seen as much of the world as any other person alive. Thirty years on, he is still on our screens.

In his latest programme, The Green Planet, about the world of plants, he is there in the field, now 95 years old, his joy undimmed, like some living embodiment of the rejuvenating capacity of intellectual passion.

But the tenor of these latest offerings has changed. Seldom does a segment pass without some reference to the myriad ways human civilisation has grown to imperil the environments on display.

One of Attenborough’s more recent books, A Life on Our Planet, is both a memoir – he calls it his “witness statement” – and a manifesto, an exhortation for “Homo sapiens, the wise human being… (to) live up to its name”. In place of wildlife spectacle, it opens in the abandoned streets of Pripyat, Ukraine, in the shadow of Chernobyl, an emblem of human self-destruction.

For many years, controversially, the old don avoided contextualising his writing and broadcasting about the natural world with caveats about its ruination. The rationale was that his job was to inspire a love of nature in wider society.

Undercutting that exposition with news of nature’s plight, however pertinent, would be a turnoff for readers and viewers, thereby alienating public support for conservation efforts.

I’ve always been torn over how to feel about this shift. Certainly, I don’t begrudge Attenborough for abandoning the policy, which was eventually overwhelmed by the urgency of our current moment.

To ignore the crisis of global biodiversity now that its true extent has crystallised would be a dereliction. Nevertheless, it’s hard not to see The Trials as a high water mark, if not of biological science and the technology deployed in its documentation, then at least in the unalloyed, childlike delight that people of any age might derive from bearing witness to it.

It is an irony of sorts that, when I began to travel in earnest, animal-watching quickly fell to the bottom of my agenda. This said less about its objective pleasures than my discomfort with the intrusive circus of careening safari vehicles and rapid-fire camera shutters. The wrong kind of context can dampen even the purest of enthusiasms.

For those of us who were young at the time of its release, the book, then, is a bittersweet artefact. Thumbing through its pages, all these years later, it is hard to avoid the sense that my fondness for it was to some extent contingent on its purity, its complete absence of critique. And that it was our good fortune to grow up in a time of innocence.