ANN/CHINA DAILY – Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was as renowned for his passion for jade as for his love of calligraphy and paintings.

During his reign (1736-1796), this fascination elevated jade craftsmanship to unprecedented heights.

He penned around 800 poems celebrating jade, expressing admiration and delight, especially upon receiving exceptional pieces. Among the treasures that inspired his poetry were Hindustani jade vessels from the Mughal Empire, which ruled India from the 16th to 19th Centuries.

These delicate, translucent artifacts – bowls, plates, teapots, vases, and incense burners – featured intricate floral and foliage designs, polished to perfection and sometimes adorned with gold, silver, and gems.

To boost jade production, Emperor Qianlong invited master craftsmen from Jiangnan, particularly Suzhou and Yangzhou in modern Jiangsu province, to work at the imperial court. For thousands of years, this region, rich in elegance and literati temperament, has been filled with artisans whose carvings have realised the material’s imagery association with human virtue.

In his later years, Emperor Qianlong made the decision to cease the production of the delicate and resource-intensive Hindustani style due to its high costs in raw materials, labour, and time. Subsequently, the craft was gradually forgotten.

MINIATURE ARTWORK

Nevertheless, a modern generation of craftsmen is tempted to restore and further refine this mysterious, superb skill.

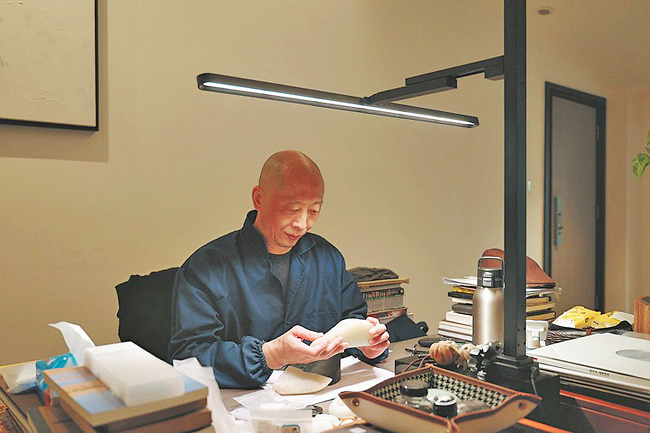

Among those investing constant efforts is Suzhou-based jade carver Yu Ting, 51, whose journey began when he discovered a book on Hindustani jade and an eggshell-thin fragment at the beginning of the century.

“Historical records say that vessels with a thickness of less than 1.6 millimetres could be called eggshell jade but, thanks to improved tools, we can now make them thinner than one milimetre (mm), even as thin as 0.5 to 0.6mm,” he said.

In his studio in western Suzhou, where his jade pieces are displayed, he arranges lights behind these vessels, so visitors can observe the thin surface with its delicately carved patterns, and the glossy, even inner walls.

He is very proud of a 34-centimetre (cm)-tall bottle with a small mouth and bulging belly, the shape inspired by short columns on the beams of traditional architecture in suburban Suzhou.

Yu and his team spent three years producing this bottle, which weighs only 478 grammes and is made from a raw material of 39 kilogrammes.

The belly is 11cm in diameter and the mouth is just two-centimetre. They had to apply mini tools to hollow out the interior a little at a time, “like cleaning ears”, he said.

While hollowing out this piece, the artisans could barely see the inside and had to rely largely on feeling with their hands.

Yu explained that it’s a risky process to make eggshell jade pieces, as a slight tremble may puncture the whole piece.

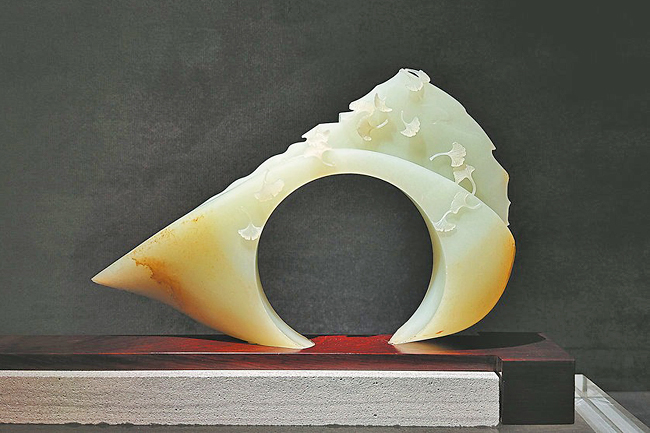

The surface of the bottle is adorned with symmetrical relief patterns featuring intertwined winter jasmine and lotus, both bearing auspicious meanings in traditional Chinese culture.

Variations in colour result from the change in thickness of the carvings on the green nephrite – with the thinner part being lighter and the thicker part with relief patterns appearing much darker.

The eggshell jade master is just one practitioner striving to protect the millennia-long prosperity of antique craftsmanship in Suzhou.

Late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) scientist Song Yingxing wrote in his masterpiece Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature) that although fine jade materials were always brought to the capital, Suzhou possessed the most exquisite craftsmanship.

According to president Ma Jianting of the Suzhou Arts and Crafts Industry Association, regional characteristics of jade carving, as well as the exchange and integration of craftsmanship, have lasted throughout the modern era.

For example, artisans in the north have inherited the traditional style of grand, complex royal pieces.

Jade artisans in Yangzhou, historically taking advantage of the convenient transportation of raw materials by the Grand Canal, are good at carving large pieces such as mountains.

Suzhou-based carvers, on the other hand, are focused on smaller pieces with delicate, reserved designs that resonate with the city’s gentle atmosphere, said the association’s Deputy Secretary-General Shan Cunde.

Representative jade carving works of Yang Xi, 60, a national-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor, include a depiction of the Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva (Thousand-Hand Bodhisattva).