Liza Weisstuch

THE WASHINGTON POST- There’s a steel black box near the entrance of the Derrick. It’s about the height of a billiards table and rather unremarkable. But when the bartender lifted the heavy cover, several people seated nearby turned their heads, captivated by the lavender light it emitted.

The bartender plucked some cilantro from fresh bunches sitting in very shallow water in the box. The UV light keeps the greens fresher longer, he told me. Moments later, he chopped them up and used them to garnish my drink – a celebration of spring’s garden freshness.

The harvest box, as it’s called, is supplied and stocked weekly by Garden Collective, a group of five entrepreneurs who grow herbs and vegetables in a 2,200-square-foot enclosed garden on the second story of an office-mall hybrid building.

My bartender said I could go see it for myself, so the next morning, I did. It’s at the end of a Plus 15, the Calgarian term for the 60-plus skywalks, each about 15 feet above the street, that connect the city’s buildings. They make up one of the world’s largest pedestrian skywalk networks. Garden Collective’s space is behind vast glass windows and across from a shop that sells diamonds. Passersby frequently pause to snap photos.

It was co-founded by Zishan Kassam, a Calgary, Alberta, native and software product manager by day. “We have the modern technology to be able to grow in a city, so why are we so reliant on supply chains that start abroad?” he said, noting how the pandemic made the situation all the more urgent.

He explained how, within the limited confines of the space, he has an unconstrained capability to adjust temperature, light and the nutrient levels in the dirt to modify the flavour and character of the herbs and leafy greens, which he sells to at least 10 restaurants at any given time.

The city has long been known for the Calgary Stampede, the century-old rodeo event that takes place every summer and typically draws more than one million visitors. But that seasonal event doesn’t define Calgary year-round.

It’s also a popular stopover for people heading to take in the stunning nature of Lake Louise and Banff National Park, which is close to the Canadian Rockies. And in recent years – thanks to a lively culinary scene fuelled by chefs who have managed to create locally focussed menus, despite the prairie city’s extreme weather – Calgary has become a destination in its own right.

It welcomes about 7.7 million visitors annually, and it’s preparing to welcome more in the coming years. Two new boutique hotels – the Westley, which opened last year, and the Dorian, slated to open later this month – will feature local chefs and art. This is part of the lead-up to the increased draw the city expects when the reimagined Glenbow, the city’s arts and culture centre, opens in 2024, the same year as the BMO Centre at Stampede Park. The expansion will make BMO Centre Canada’s second-largest convention centre.

Major Tom is one of the restaurants that uses Garden Collective’s bounty. The glam-yet-laid-back spot is on the 40th floor of an office tower. If you face west and squint, you can make out, in the distance, a ski jump turned zip line in Canada Olympic Park (or WinSport, as it’s known today), site of the 1988 Winter Olympics.

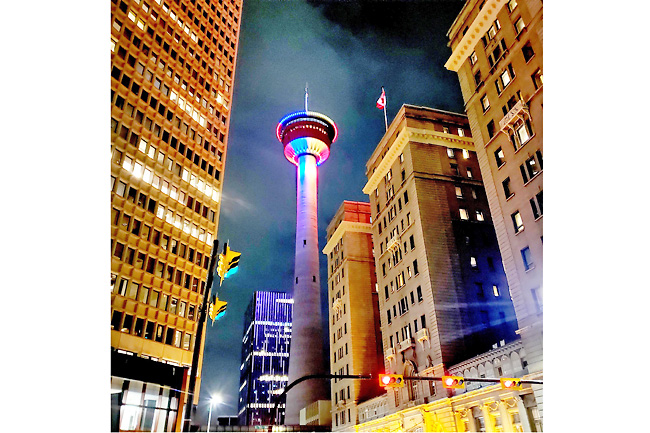

The Calgary Tower, a major tourist attraction, is a few short blocks away. On a Thursday in May, the city below twinkled all the way to the horizon, but the more radiant part of the evening was the baked Pacific lingcod, served with charred eggplant, olives and green-tomato vierge, a French interpretation of marinara sauce. Marigold petals from Zishan and the crew were scattered on top.

Culinary director Garrett Martin told me he visited Garden Collective that afternoon for a tasting, and explained the process.

“If we don’t think something has enough flavour or needs sweetness, they just manipulate the water content, light or heat exposure to get different results. They’ve been doing a lot of tweaking for us, and it’s been coming through nicely,” he said. The team once grew dill, but it didn’t pack a lot of a punch, Garrett recalled. A few weeks later, they brought back a more dilly dill. “I love to support local, but it has to be good,” he said.

“Locally grown” is a common priority these days. More and more chefs, restaurateurs and bartenders focus on area specialties in the interest of highlighting regional bounties, cutting carbon footprints and supporting local farmers and makers.

But that’s challenging in some places, such as Calgary, where the growing season is short and plagued by hail, wind, and unseasonal snow and frost.

But over the week I spent there in May, I found a city that operates like a sturdy Möbius strip, a system closed in on itself, yet mesmerising in how it functions.

It’s something I saw in high-definition at Rouge, which serves modern dishes in a historical house with creaky floors and Victorian flourishes.

The restaurant gained widespread acclaim when it notched a spot on the San Pellegrino World’s 100 Best Restaurants list in 2010. But more recently, one of its claims to fame is co-founder and culinary director Paul Rogalski’s role in Wild Harvest, an outdoor adventure and cooking show that airs on PBS stations across the United States. He co-stars with producer Les “Survivorman” Stroud. Les forages, Paul cooks. It has informed the dishes served at Rouge.

He offered to show me around the garden out back, where he has a beehive, a greenhouse, and beds of herbs and veggies.

As we walked, he told me about the rewards of experimenting with spruce tips in the kitchen, and the abundant chickweed – whose name is tragic to him. (“Nothing is a weed.

It’s either prolific and invasive or not.”) He plucked the sweetest asparagus I’ve ever known, as well as sorrel, which I’d later have in a tangy sauce in a fish dish. He pointed out crab apple blossoms, which made an appearance in dessert.

Proprietor of River Café Sal Howell has a similar philosophy. River Café is located on the tiny, quiet Prince’s Island Park on the Bow River, a 365-mile body of water that’s fed by the glacial runoff of the Canadian Rockies.

The island is about a mile from downtown, but it feels a universe away. Sal founded the cafe in 1991 as a concession stand, but built it out into a fishing-lodge-inspired wonderland, complete with a hanging birch-bark canoe and hickory furniture. The place serves Canadian Rocky Mountain cuisine.

“There’s rhubarb coming up. And I see lovage and chives – lots and lots of chives,” she said, pointing to the different greens poking up from the garden that wraps around the building. She leaned over and plucked a few lovage leaves for each of us. It struck me as celery’s alter ego, its feathery leaves slightly peppery with a fleck of anise.

Howell’s kitchen staff makes clever use of what most people would dispose of, which results in creations such as vinegar.

Sourcing local here is an extreme sport. Lamb, grains and seafood are easy enough to get, but when it comes to citrus, olive oil and other pantry staples that have no place on the Canadian prairies, it’s more challenging. But they pull it off beautifully.