Jake Coyle

AP – Anime master Mamoru Hosoda makes movies that, even at their most elaborate, can reach such staggeringly emotional heights that they seem to break free of anything you’re prepared for in an animated movie – or in most kinds of movies, for that matter.

Any talented Japanese filmmaker working in fantastical animation inevitably draws comparisons to the great Hayao Miyazaki. But the more appropriate touchstone for Hosoda may be Yasujirō Ozu. As dazzling as Hosoda’s films may be visually or conceptually, they’re rooted in simple and profound human stories.

His last film, the Oscar-nominated Mirai, is one of the best movies made in recent years about family. It centred on a four-year-old boy who, dealing with the arrival of a new baby sister and confronting new feelings of jealousy, is visited by his sister as a middle-schooler. Other time-travelling encounters follow, and a new understanding and empathy grows in the boy.

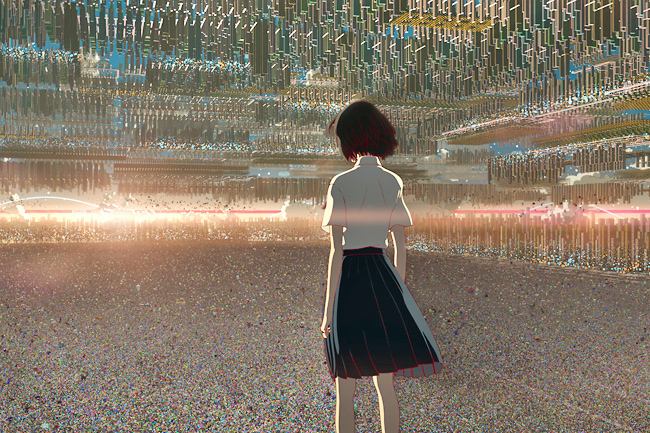

Hosoda’s latest, Belle, is more complicatedly sketched. It’s an ultra-modern take on Beauty and the Beast that transfers the fairy tale to a digital metaverse realm called ‘U’. There, in a dizzying digital expanse that will satisfy any Matrix fan who felt let down by the virtual worlds of The Matrix Resurrections, its five billion users can adapt any persona they like.

The 17-year-old Suzu (voiced by Kaho Nakamura in the subtitled version I saw; an English dub is also playing) reluctantly joins U as an avatar named Belle, a more exotic beauty than the modest and shy Suzu. In the U, Belle’s songs find massive stardom that’s much unlike Suzu’s own life, where one of her only friends is Hiroka (Lilas Ikuta), a computer whiz who helps craft Belle.

In U, Belle finds herself drawn to the metaverse’s notorious villain called the Dragon (or the Beast) who’s hunted by a police-like force that wants peace and free-flowing commerce in U.

You might be thinking that an anime Beauty and the Beast turned into Internet parable sounds a tad overelaborate – and about the furthest thing from the sage simplicity of Ozu.

It’s indeed a lot that Hosoda is going for here, and Beauty and the Beast doesn’t always seem a useful form for all the ideas floating around. At times, Belle bends and cracks under its grand ambitions.

But the heart of Hosoda’s sincere film never falters. Taking place in both modern-day Japan and the virtual U, its foot in reality is firmly planted.

Our first vision of Suzu is as a young girl watching her mother, in an act of brave selflessness, lose her life saving a child from a flood.

Loss and grief have consumed Suzu’s childhood; her virtual transformation into Belle is a chance to free herself from some of her everyday struggles. Music had been part of her bond with her mother.

That tragic backdrop – how we treat strangers – is also part of the lessons of U, where anonymity breeds good and ill. On the whole, this is a surprisingly positive view of the capacity of the Internet for connection and liberation. But what’s most striking is how Hosoda marries both realities despite their vast differences. Each world shimmers. Clouds are rendered as mesmerising as anything in U.

The movie ultimately resides, intimately, with Suzu. Even with all that’s going on, Belle is deeply attuned to its protagonist’s hurts, memories and dreams. Every moment flits between her past and present, reality and virtual reality.

These worlds ultimately merge in a scene of astounding catharsis – a song sung not by Belle, but Suzu – and it’s one of the most intensely beautiful moments you’re likely to see, anywhere.