Delight in the art of fermentation with Lun Bawang’s culinary treasures of nuba laya and senamu lawid.

Everyone adores food, not just for the joy it brings but also for the essential nutrients it provides. As a fellow food enthusiast, I’m always eager to try new dishes.

For many of us, frequent travel not only immerses us in diverse cultures, traditions, and lifestyles but also allows us to savour delicacies unique to each destination.

However, even if you aren’t a globetrotter, there are still local ethnic dishes waiting to be explored.

I’ve always been captivated by local ethnic cuisines and often find myself indulging in these dishes, not just to satisfy my curiosity but also to confirm the authenticity of the stories people share about the food.

Recently, I had the chance to try traditional Murut dishes during a visit to a relative’s home. The relative’s spouse is of Murut lineage (also known as Lun Bawang), and to my delight, some family members from the spouse’s side were also present. They graciously prepared a selection of local dishes, providing us an authentic taste of their cuisine.

A TALE OF FERMENTATION

The Lun Bawang, historically peasant farmers cultivating hill rice and wet paddy are renowned for their organic practices as evident in their staple dish, rice cooked in banana leaves known as nuba laya.

Abundant rice harvests prompted them to develop unique preservation methods, utilising rice to preserve meats and fish, showcasing their resourcefulness and culinary innovation.

In the absence of refrigeration, they employed a unique method – seasoning meat and mixing it with cooked rice, then storing it in hollow bamboo stalks buried in soil for a month.

While such practices have waned with the newer generation, the essence of preservation persists.

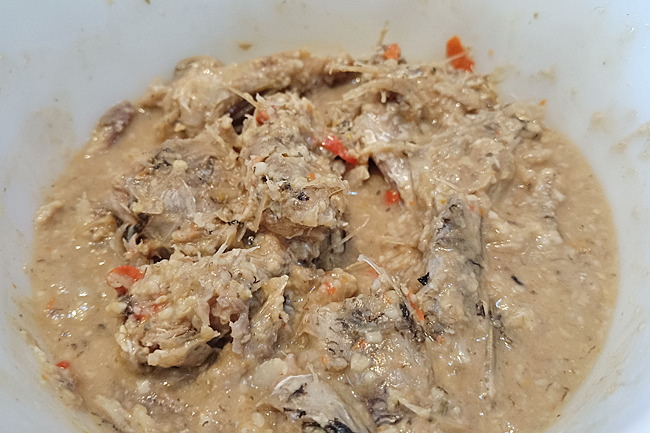

During my visit, I had the chance to experience senamu lawid, a fermented fish dish central to Lun Bawang traditions.

Nowadays, seasoned meat or fish is stored in containers in darker areas at room temperature. Surprisingly, my trial of senamu lawid blended with nuba laya revealed a delightful absence of the expected fermented taste.

Instead, it was replaced by a delightful sour note, a flavour profile I found complemented perfectly with Ambuyat.

Impressed by these culinary delights, I seized the opportunity to learn the preparation methods. I hope to spread the Lun Bawang traditions by sharing the recipes.

NUBA LAYA

To prepare the nuba laya, simplicity is the key. Start with a cup of short-grain rice, thoroughly washed, and combine it with three cups of water. Allow it to simmer on medium heat, ensuring a watchful eye to prevent the rice from drying out. If needed, adding another half cup of water works wonders.

Unlike regular rice, the cooking process for the nuba laya, diverges from the conventional. Here, occasional stirring is crucial. The outcome? A unique texture, reminiscent of both rice and porridge with its sticky thickness.

Crucially, the magic of nuba laya lies not just in its preparation but in its presentation as the cooked rice is wrapped in ngirik leaves. This process allows the heat to coax out the delightful herbal aroma from the ngirik leaf so that once ready, unwrapping the leaf reveals a burst of fresh fragrance.

SENAMU LAWID

For this fish dish, the Lun Bawang people prefer freshwater fish, believing it yields the best flavour when fermented.

After cleaning and drying the fish, season it with salt. Then, mix it thoroughly with a generous amount of cooled cooked rice.

This mixture is placed in a glass container, left to ferment for two to three weeks.

The beauty lies in its simplicity, although patience is key – it’s a waiting game. Mixing the fish with cooked rice works like magic, naturally “cooking” the fish during fermentation. After three weeks, your well-fermented senamu lawid is ready.

Pair it with nuba laya and add local veggies like tapioca leaf or bamboo shoots and you’ll find yourself indulging in at least two packets of nuba laya. Enjoy your meal! – Lyna Mohamad