Ron Charles

THE WASHINGTON POST – Three years ago, Booker Prize winner Marlon James sliced through enough carotid arteries to fill an ocean.

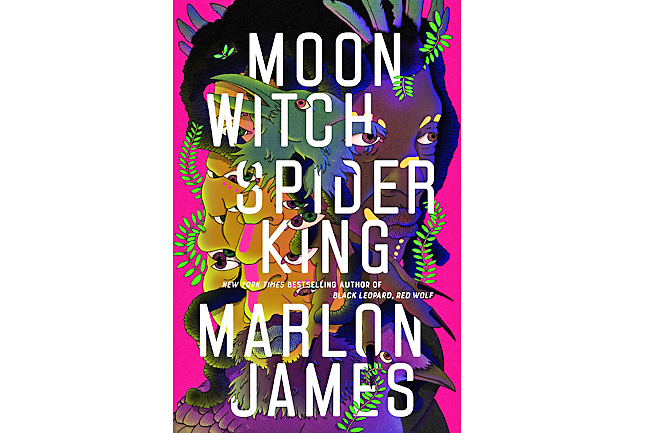

Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the first volume of his Dark Star trilogy, washed into fame on a wave of blood.

James joked that he was writing “an African Game of Thrones,” but his real target was higher and older: He reanimated modern fantasy with the bones and sinews of African mythology. The result was a genre-stretching, canon-scrambling triumph that The Washington Post called one of the top 10 books of the year.

In an ancient world riven by war, “Black Leopard, Red Wolf” spins a story about the search for a boy who may be the key to the kingdom’s survival. Much of the book – a collection of adventures oxidized by the mist of legend – describes a posse that sets off to find the lost child. Throughout their years-long search, the Red Wolf and his lover, the shapeshifting Black Leopard, work in uneasy collaboration with a buffalo, a melancholy giant and a witch named Sogolon.

That old woman, who insists she’s not really a witch, is now the subject of the second volume of the Dark Star trilogy. Moon Witch, Spider King is a companion rather than a sequel to the earlier book. Its story begins more than a century before the adventures of Wolf and Leopard – indeed, you’ll want to sit down: They don’t appear in this new volume for 500 pages.

This is the memoir of a reluctant killer, a 177-year-old disconsolate woman who claims, “I never have a happy day ever.” She wants nothing more than to be left alone or to die. She never gets either wish. “Everything annoy me,” she says in her heavy patois. “Everything aggravate me, and all things work together to make me bitter.”

Sogolon’s bitterness germinates early in life, when she’s kept on a leash and terrorised by a trio of brothers, “all wicked.” She finally manages to run away after blinding one sibling with her urine and chopping off his hand. It’s that kind of family.

Sogolon finds working in a whorehouse something of an improvement. But she’s eventually passed off as a gift to the princess of the Akum dynasty, mother of the future king of the empire. Not quite an enslaved woman nor a companion, Sogolon hovers in a precarious position. The palace, after all, is a place in which subjects are whipped, dismembered and fried for the tiniest infractions. But even at the risk of losing her life, Sogolon shows deference to no one, a quality we see on display in stretches of caustic dialogue that are often shockingly funny. Remarkably, her pugnacious attitude amuses the princess, who grows to rely on the young “bush girl” for her refreshing candor.

Once in the capital, James sinks deep into the filial and political dysfunction of the kingdom. His description of the Akum dynasty glitters with Swiftian absurdity, starting with a series of royal palaces constructed and then abandoned for the ascension of each new king. What’s more, the screwy structure of succession in this realm essentially guarantees murderous tensions within the royal family.

But if the kingdom is in a constant state of upheaval, there’s a presence that remains constant, year after year, even decade after decade: the king’s chancellor, known as the Aesi.

“Some kind of diminished divine thing,” the Aesi is a freakishly tall man with red hair and skin the colour of dark green moss.

This malevolent official exercises control, in part, by launching witch hunts that keep the capital in a state of perpetual paranoia and litter the streets with the bodies of executed women.

Among his supernatural powers is the ability to wipe away people’s memories, a handy tool for confusing the royals, disappearing his enemies and scrambling the path of succession to the throne.

But there’s one person whose mind the Aesi can’t erase: the young woman known as Sogolon. Her mental resistance attracts his attention early and points to a cataclysmic confrontation on the horizon. The horizon, though, is a long way off.

While the Leopard and the Wolf spring up immediately as virile action heroes in the first volume of the Dark Star trilogy, in this new volume James moves slowly to develop his reluctant female warrior. For years, Sogolon has no sense of her special power. What she calls “the wind (not wind)” comes to her rescue and blows away her enemies, but it remains mysterious and undependable.

It’s only after Sogolon suffers a crushing loss that she fuses her grief and anger into a fearsome weapon of vengeance. Like an ancient predecessor of Lisbeth Salander, she dedicates her lonely life to answering the calls of abused girls and women. They search her out in the forest “with a mountain of problems, and nine times out of ten, that problem is a man,” she says. “I stop being a woman, stop being an instrument of revenge, and start to be folklore.”

But even that rarefied role makes her feel uncomfortably constrained. “She want people to know her only by her trace,” James writes. “She want to move.”

I want her to move, too. When Sogolon is moving, Moon Witch, Spider King comes spectacularly alive. James choreographs fight scenes that make Quentin Tarantino’s movies feel comparatively tranquil. And there’s a catalogue of diabolically ingenious creatures creeping along the ceilings, jumping from behind trees and even reaching through fourth-dimension portals to keep the pages simmering with terror.

In its structure and pacing, though, this is a different novel from Black Leopard, Red Wolf.

The previous book was certainly difficult, but it was a grand quest, charging forward with inexorable momentum, luxuriating in its vast length to unspool a series of adventures.

Moon Witch, Spider King, on the other hand, is the confession of someone nursing a horrible anger and a consuming sorrow. As such, the story sometimes skids into pits of rumination that increase the narrative’s persistent fogginess.