Sylvia Chan-Malik

THE WASHINGTON POST – Wellness is something we all want – to be well, even as the world crumbles around us.

But as shows such as The White Lotus and Nine Perfect Strangers demonstrate, wellness has become a commodity, geared toward the wealthy, White and able-bodied, who seek to shiatsu and savasana their way out of late-capitalism though mindfulness, dewy skin and a Pilates-sculpted core.

For less-privileged others, wellness is an unattainable luxury, gatekept by racism, ableism and fatphobia, and thus cordoned off from those who need it most, eg the poor, workers and people of colour.

Indeed, as online essays on toxic wellness culture and recent books like Kerri Kelly’s American Detox and Dalia Kinsey’s Decolonizing Wellness argue, wellness is not well.

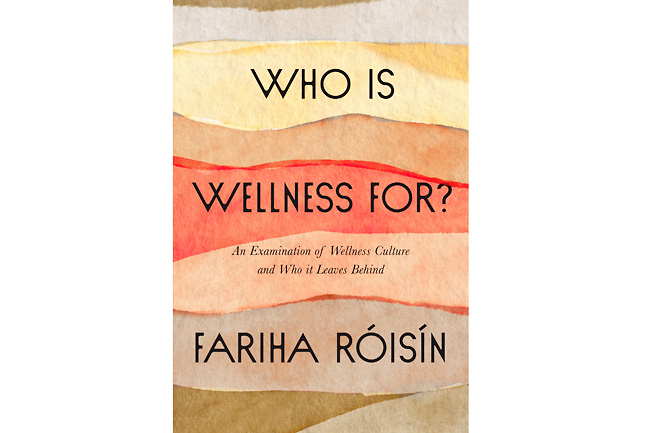

Fariha Róisín’s new book, Who Is Wellness For? An Examination of Wellness Culture and Who It Leaves Behind, tracks the author’s “own personal experience of needing wellness”, while simultaneously examining the wellness industrial complex and its failures.

Róisín, author of the poetry collection How to Cure a Ghost (2019) and the novel Like a Bird (2020), identifies as a Bangladeshi Muslim, part of a new generation of Black and Brown women of colour writers who – following in the tradition of Black feminist poet-scholar-activists such as Audre Lorde, June Jordan and bell hooks (all of whom Róisín names as heroes) – take up themes of trauma and identity through a social justice lens.

For Róisín, healing and self-discovery are closely tied to collective reckonings with lived legacies of racism and colonialism, as well as sexism. As Who Is Wellness For? argues, healing is an integral – if not the most – important step toward liberation from such legacies.

Róisín’s journey begins with her desire to heal from her mentally ill mother’s psychological, physical and sexual abuse, which she describes in the book’s opening as leaving her body “forever in a state of distress”.

The abuse is compounded by the author’s ever-increasing awareness of being a Brown Muslim woman in a White settler-colonial world.

Róisín, who grew up in Australia, and later moved to Montreal and New York City, writes harrowingly of her inability to escape – as she quotes from psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk’s best-selling title, The Body Keeps the Score.

Soon, she encounters her trauma not only in her thoughts, but in her body – as she struggles with severe body dysmorphia and irritable bowel syndrome – and her relationships, which are fraught with manipulation and harm.

Yet the search for “wellness” continually brings Róisín to spaces that amplify her trauma – an all-White yoga studio in Montreal, a massage therapist who speaks dismissively of Dylan Farrow’s abuse allegations, toxic female friendships.

The book takes readers through what Róisín describes as the four aspects of wellness – mind, body, self-care and justice.

Through each section, she acts simultaneously as subject and scholar, sharing her own stories of struggle and healing, which are peppered through with academic and scholarly references.

This works well at times, for example when Róisín describes how early in her healing journey, she encounters yoga, surmising that she is drawn to it at age 13 because “it was the closest tangible understanding that I had to being South Asian”.

While there have been numerous critiques of yoga’s cultural appropriation (and corruption) by White practitioners in the West, Who Is Wellness For? astutely takes such criticism a step further, highlighting how British colonisers approved of particular forms of yoga as practiced by upper caste Indians, while displacing those of the homeless and poor.

At other times, however, Róisín’s narrative shifts can be jarring, moving abruptly between her personal experience and academic analysis.

And while the book is critical of the wellness industry’s decontextualisation of its practices’ cultural, ethnic and spiritual origins, Róisín herself often cites Black and Indigenous women scholars and writers (such as Lorde, Jordan, and hooks, as well as Robin Wall Kimmerer, Winona LaDuke and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson) with little engagement with the histories of violence and struggle that produced their desire to heal.

So, who is wellness for? Róisín’s poignant response to her own question is that our healing must be collective, accessible and available to all: “Wellness isn’t for anyone if it isn’t for everyone. Otherwise, it’s a paradox.”

This may be the book’s most important takeaway – that what we need isn’t “wellness” but a justice-based ethos of reciprocity, compassion and care.