Dawn Turner

THE WASHINGTON POST – Michelle Obama’s 2018 memoir Becoming was a phenomenon: It broke sales records and turned the former first lady into a whole new kind of celebrity. To follow up, Obama planned to write another inspirational book about how she overcame adversity. But the uncertainty and upheaval from the pandemic, the continued killings of Black people by police and the crimes against Asians, and the January 6, 2021 assault on the United States (US) Capitol broadened her reach and demanded a different course.

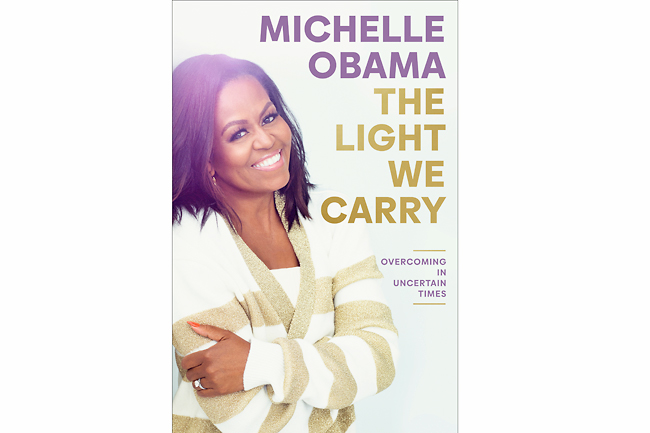

The result is The Light We Carry: Overcoming in Uncertain Times. The title refers to the importance of recognising one’s own light and becoming empowered by it. The book emerged, in part, from admirers’ queries, and while Obama readily admits she doesn’t have all the answers, she can offer her “toolbox”, the techniques and strategies she uses to manage her self-doubt and anxieties, and ward against hovering cynicism and low-grade depression.

Her strategies include the support of family and friends and hobbies such as knitting, which she picked up during the pandemic. It allows her to focus on the “power of small actions, small gestures, small ways you might allow yourself to reset and restore”.

Although reaffirming, the advice isn’t groundbreaking. What makes the book special is that it builds on parts of Becoming, and Obama serves as mentor and guide, using pivotal moments in her life to demonstrate when she had to rely on boldness, pluck and grit as she made her way from a second-floor apartment on Chicago’s South Euclid Avenue to the Ivy League to what she describes as a “132-room palace, surrounded by guards”.

She opens with her beloved father, Fraser Robinson III, and tells the story of how his struggles with multiple sclerosis, his unsteadiness with walking, instilled in her early lessons on finding her footing and developing the tools for balance. It’s what she calls “staying upright inside of challenge and change”.

She writes about learning to be “comfortably afraid” – using fear to steer, rather than hinder – and how her worries could have thwarted her husband Barack Obama’s run for the presidency because he offered her the final say on whether he launched his campaign. “It’s strange to think that I could have altered the course of history with my fear,” she explains.

Despite her extraordinary gifts and accomplishments, Obama acknowledges that she worries about her looks; finds the label “angry Black woman” reductive; and is still pursued by the nagging question: “Am I good enough?”, especially in spaces that prize straight White maleness over differences. Her father often told her, “No one can make you feel bad if you feel good about yourself.” To that, she responds: “It took me years to absorb my dad’s maxim more fully into my own life. I grew into my confidence slowly, in fits and starts. Only gradually did I learn to carry my differentness with pride.”

Much of this ground may be familiar, particularly to anyone who has read Becoming. The book’s more surprising and dynamic passages unfold on the political front.

A “Who knew?” moment focusses on her prime-time address during the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver. She walked onto the stage at the Pepsi Center, prepared to deliver a live speech – after being introduced by her brother, Craig Robinson – and realised that one of the two teleprompters wasn’t working. She was happy that she memorised her speech.

The moment crystallised an important lesson: Always be prepared.

Obama doesn’t hold back about her anger and frustration at former president Donald Trump and the way he handled the pandemic and the assault on the Capitol. She talks about the sadness she felt after the 2016 election and about the fact that so many Americans viewed Trump as a sort of corrective to her husband. It made her question whether the Obama years had meant anything.

“It still hurts. It shook me profoundly to hear the man who’d replaced my husband as president openly and unapologetically using ethnic slurs, making selfishness and hate somehow acceptable, refusing to condemn white supremacists or to support people demonstrating for racial justice. It shocked me to hear him speaking about differentness as if it were a threat,” she writes.

One of my favourite chapters is on Obama’s mother, Marian Robinson, wholly recognisable to me as a no-nonsense, forthright matriarch who made me smile every time she was on the page.

We all know that Robinson wasn’t keen on moving into the White House. But what’s new here is a wonderful story about how Robinson made her daughter, a kindergartner at the time, walk a block and a half alone to school – so she would learn how to be competent and unafraid.

“What she offers is perspective and presence,” Obama writes of her mother. “She is an engaged listener, someone who can quickly banish my fear to the back of the room or rein me in when I’m getting a little ‘extra’ with my fretting.”

Sure, the words are inspiring. “When they go low, we go high,” the mantra that has come to define Michelle Obama. Not surprisingly, those words were a call to action and a natural outgrowth of her upbringing and her marriage.

“All I was doing, really, was sharing a simple motto that my family tried to live by, a convenient bit of shorthand Barack and I used to remind ourselves to hang on to integrity when we saw others losing theirs,” she writes.

“It was a simplification of our ideals, a soup pot full of ingredients, everything we’d gleaned from our upbringings that had been simmered into us over time: Tell the truth, do your best by others, stay tough. That’s basically been our recipe for getting by. “

If that’s all you take from this book, it’s enough.