Steven V Roberts

THE WASHINGTON POST – Good sportswriting is not mainly about who won the game. It’s about who played the game – their flaws and fears, triumphs and tears.

It’s also about the social setting in which those games are played, about the way sports reflect and reveal our humanity.

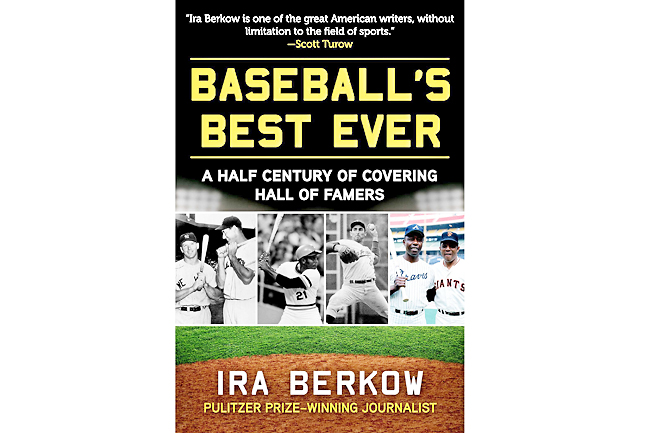

In this collection of his newspaper columns, Baseball’s Best Ever: A Half Century of Covering Hall of Famers, Ira Berkow quotes another sportswriter, the immortal Red Smith, on this point: “Games are a part of every culture we know anything about… The man who reports on these games contributes his small bit to the record of his time.”

Berkow, who wrote mainly for the Newspaper Enterprise Association syndicate and then for the New York Times, donates more than a “small bit” to that record.

I often found myself skipping over the statistics and the standings he writes about – we already know what happened, after all – and focussing on the personal stories, especially the ones about failure and disappointment.

Here for instance is Mickey Mantle, a boyhood idol of mine, who told Berkow in 1971, three years after retiring from the New York Yankees: “Playing baseball is all I’ve ever known. It makes me kind of bitter that it’s all over. You look around and see other guys my age, other guys forty years old, who are just starting to reach their peak in other jobs. And I’m finished.”

Some statistics can be fascinating, however, and one of my favourite columns features all the ways in which baseball’s biggest stars screwed up.

Warren Spahn, one of the best left-handed pitchers of all time, gave up 434 home runs.

Babe Ruth led the majors in strikeouts in four different years and whiffed 1,306 times – a benchmark for decades until Mantle flailed even more often. The record for grounding into double plays in a single World Series is seven – held by Joe DiMaggio. “At times, as the evidence shows, even the greatest among us aren’t great, or even very good,” Berkow wrote. “Somehow, though, that’s heartening.”

All collections of previously published pieces contain strengths and weaknesses. They can capture moments in real time, unfiltered by false nostalgia or faulty memory.

But they can also feel dated and repetitive. Too many columns here focus on anodyne speeches by Hall of Fame inductees and elegiac tributes to recently departed old-timers.

But at his best, Berkow can turn a phrase like an all-star second baseman turning a double play.

Here he describes Ozzie Smith, the ineffable shortstop of the St Louis Cardinals: “He leaps, he dives, he whirls. He seems to appear behind second base as if popping from underground; he can soar and stay aloft like a hummingbird and wait for a line drive to arrive.” Of Kirby Puckett, a rotund yet robust hitter for the Minnesota Twins, Berkow says that he “is built like a keg of dynamite and periodically explodes like one”.

One of this volume’s recurring themes is the intersection of race and baseball, and Berkow has a creative way of showing the impact of Jackie Robinson, who integrated the sport in 1947.

He turns to Ed Charles, a journeyman infielder in the 1960s, who recalled “the biggest day of my life”, when he was 13 and Robinson came through his hometown in Florida with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“I realised then I could play in the major leagues,” Charles said. “When it was over, we chased the Dodger train as far as we could with Robinson waving to us from the back. We ran until we couldn’t hear the sound any more. We were exhausted but we were never so happy.”

For another angle Berkow interviews Larry Doby, who integrated the American League just after Robinson’s debut and remembered the loneliness of being a pioneer once the games were over: “It’s then you’d really like to be with your teammates, win or lose, and go over the game. But I’d go off to my hotel in the black part of town, and they’d go off to their hotel.” I laughed a lot, too. One of my favourite characters is Lefty Gomez, a southpaw pitcher with the Yankees in the ’30s who once said about the slugger Jimmie Foxx, “He’s got muscles in his hair.” Lefty’s catcher Bill Dickey recalled a game when Gomez kept shaking off his signs as Foxx came to bat.

Finally Dickey ran out to the mound and asked Lefty what he wanted to throw.

“I don’t want to throw him nothin’,” replied the pitcher. “Maybe he’ll just get tired of waitin’ and leave.”

A big part of baseball, often hidden from the fans, is the nagging injuries that plague many players – especially catchers – during a six-month season.

Said Johnny Bench, one of the best backstops ever, “I’ve been shot up with so many painkillers to stay in the lineup that if I were a race horse I’d be illegal.”

Rod Carew recalled rooming with Tony Oliva, an outfielder who had suffered torn cartilage in his knee: “I’d be asleep and wake up and hear Tony cry like a baby in the night because of the pain.”

Finally here are two bits of folk wisdom that apply to sportswriters (and book reviewers) as well as ballplayers. One comes from the old Cardinals pitcher Dizzy Dean: “I ain’t what I used to be, but who is.” And this one from hurler Catfish Hunter, a country boy from North Carolina: “The sun don’t shine on the same dog all the time.”

True enough, but the sun shines on, and through, enough of these columns to make this collection well worth reading.