Jen Rose Smith

THE WASHINGTON POST – When cancelled flights and plans loom, and the pandemic seems to make my world uncomfortably small, I find myself staring out the front door while thinking once again of the young Laurie Lee.

On a fine sunny day in 1934, a 19-year-old Lee walked out of his family home in a Cotswolds, England, hamlet that, an Internet search suggests, looked very much like the Shire. He carried a violin and a little food. Though he had no fixed plan in mind, the journey would continue until he reached the fishing village of Almuñécar, on Spain’s Mediterranean coast.

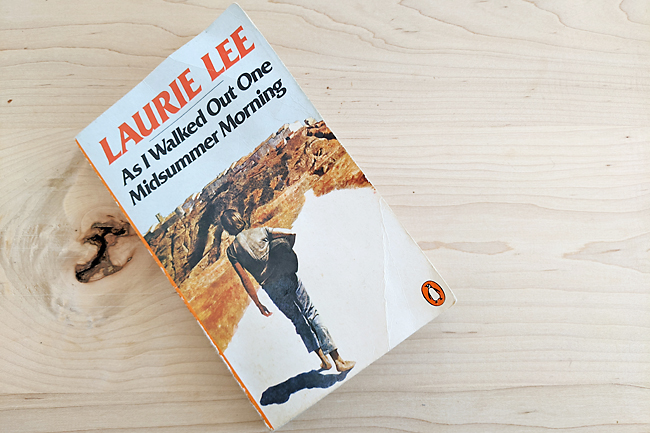

“I was nineteen years old, still soft at the edges but with a confident belief in good fortune,” Lee wrote more than three decades later, in the opening pages of his 1969 memoir of the journey, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning. Lee was a poet, and his minutely worked prose turned the slim book into a travel classic. It’s a paean to adventure on foot and the pleasures of travelling light in every sense – a welcome tonic for wearying times.

By the time he published his travelogue, Lee was already famous in his home country for Cider With Rosie, a memoir recounting village life in bucolic terms. But while the earlier book reveled in the pleasures of home, Midsummer Morning celebrates the joy of walking out the door without looking back. Lee leaned into the nearsighted urgency and thrill of youth.

“As I left home that morning and walked away from the sleeping village, it never occurred to me that others had done this before me,” wrote Lee, who would spend that first night away sleeping in a field, waking to a cold and miserable rain. English roads teemed with men turned vagrant by penury; Spain was on the cusp of war. But 30 years of remembering can turn even tales of hardship into charmed interludes.

“I was at that age which feels neither strain nor friction, when the body burns magic fuels, so that it seems to glide in warm air,” he wrote of his journey’s early days. Later, running out of food in the hills above Vigo, Spain, he remembered “a deliriously sharpening hunger, an appetite so keen it seemed almost a pity to satisfy it, so voluptuous it was”.

Gilded passages such as these could induce eye rolls – does anyone like blisters and an empty stomach? But reading Lee’s descriptions of his days in the sun-seared Spanish landscape, I recall the words of travel writer Lesley Blanch, who wrote that childhood lends “the mystic gift of consecration, of steeping things in our soul’s essence”. At times Lee seems nearly a child himself; in the sole photograph taken of him on the journey, he stands silvered and hazy, his pale features vague as bread pulled too soon from the oven.

His youth consecrated the journey, adding magic to things both dark and mundane, so it’s a pleasure to walk alongside as Lee continues south, playing his violin for tossed coins in villages that evoke fable or fairy tale. Black-robed crones lean in doorways, and merciful strangers offer aid just as sunstroke grows dire. In one town, veiled women winnow golden grain; arriving in the next, he finds elegant but impoverished residents strutting lace and velvet attire on streets lined with hovels.

Is all of it true? I have wondered how even the most detailed of notes could produce, more than three decades after Lee returned to Britain, a factual account so fine-grained and vividly told. Lee biographer Valerie Grove said Cider With Rosie was “muddled with half facts”; some critics questioned the veracity of Lee’s later memoir, A Moment of War, in which he recounted fighting as part of the Republican International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. Travel writing, too, has a long history of brazen invention.

For my part, I’m untroubled by fact-checking these tales. It’s enough that Lee, more than any writer I know, captured the transformative power to be found in a certain kind of walking journey. With its slow intimacy, walking is not just a way to go places, but also a means of knowing them differently. Walking changes the way we experience our world, awakening wonder in places that could seem otherwise, well, rather pedestrian.

And as a dedicated traveler facing a slew of trips given up in the early days of the pandemic, I found myself walking a great deal indeed. In my home state of Vermont, even trail systems were closed at the time. Instead, I walked the unnamed and untended paths that wound through the suburban wilds around my house. That compact world seemed to grow wider and more detailed with every step.

Making a circuit of the same abandoned logging roads day after day, I followed subtle shifts in the green and froggy scent of approaching spring. My feet traced the logic of landscape.

I hugged waterways and natural contours, then emerged into backyards a few neighbourhoods over.

One early spring morning, I packed a lunch and walked out my front door, curious how far I could get by following a power line corridor that slices through the mountains where I live.

The path cut across several roads I drive almost daily, but walking cross-country has a way of making familiar scenes strange.

Which is the precise opposite of air travel, I thought on a midmorning break, while sitting on a stump and eating an orange. For those with the means and inclination, flights had become effortless in the years before the pandemic. The ease of hopping from Singapore to Sweden offered the illusion of a small world, smoothing a veneer of familiarity over differences of culture, landscape and environment – but walking exposes that familiarity as superficial.

On foot, the world will always be vast and varied, because there’s no skimming over the places in between.

Just a day’s walk from the Cotswolds village where he grew up, Lee noted fine alterations in local speech patterns. Southampton’s briny scent began to prickle the air; he caught his first glimpse of the sea. Lee reveled in the immensity of what is, by most any standards, a pretty small corner of a pretty small country.

“A motor car, of course, could have crossed it in a couple of hours, but it took me the best part of a week, treading it slowly, smelling its different soils, spending a whole morning working around a hill,” he wrote. Even when living on a handful of figs, Lee found luxury in that slowness, in a world explored step by step.

“Never in my life had I felt so fat with time,” he recalled in a later passage, when he was trekking south from Valladolid, Spain.

On that rambling walk in the first pandemic spring, I followed the power line as far as I could, then branched onto muddy tracks that turned to snow in the shady hollows. Where sunshine pooled, I found boulders to rest on; once I watched a pert red fox nose patches of frozen earth.

Cold dusk had fallen before I reached the final road, legs tired after some 15 brushy miles of cross-country walking. I wasn’t far from home, but the familiar hills around me seemed newly expansive, full of possibilities and unexplored corners. I felt deliciously fat with time.